It is not an overstatement to suggest that the World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB) hold a pre-eminent position within Australia’s aid program. For the past decade, under both Coalition and Labor governments, they have been described as either the ‘key’ or ‘central’ partners of the Australian aid program. Other than AusAID itself, the banks are the largest channel for delivering Australian aid. In 2009, the World Bank was the single largest recipient of Australian aid at $508 million. In that year we directed more money to the World Bank than we did to Indonesia.

Moreover the significance of the banks in the aid program is only likely to grow as the aid budget swells. Earlier in the year, the Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness recommended a rapid trebling of funding to both the World Bank and ADB, and it furthermore recommended that Australia join the African Development Bank.

Despite this, there has been surprisingly little debate or discussion about the role of the banks in Australia’s aid program, and indeed there is a lack of data that clearly describes this role. If you were to read the little that has been written over the past few years, you would get the impression that the money that Australia gives to the banks is ‘below average’, and declining. Neither of these is true.

It is for these two reasons – the lack of clear data and the lack of debate – that Manna Gum and Oxfam Australia have produced a new report - Banking on Aid: An examination of the delivery of Australian aid through the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. The full report can be downloaded from our website or you can contact us for a hard copy. What follows are some tidbits from the report.

The role of the banks in Australian aid

The World Bank and ADB have been regarded as the “key” or “central” partners of Australia’s aid program by both Liberal and Labor governments. The reasons usually cited for this privileged role are: their ability to influence recipient government policy, their large scale (more bang for your buck), their extensive research and technical expertise, and their lower transaction costs (it is a cheaper way of delivering aid). However, perhaps central to the privileged place of the banks in Australian aid is their role as the premiere advocates of a global economic order to which Australian governments (of both major parties) have firmly staked Australia’s economic interests. Economic self-interest and frameworks for aid cannot be disentangled here — the policies that the Australian Government believes will reduce poverty are one and the same as those that it believes will benefit Australian trade and commercial interests.

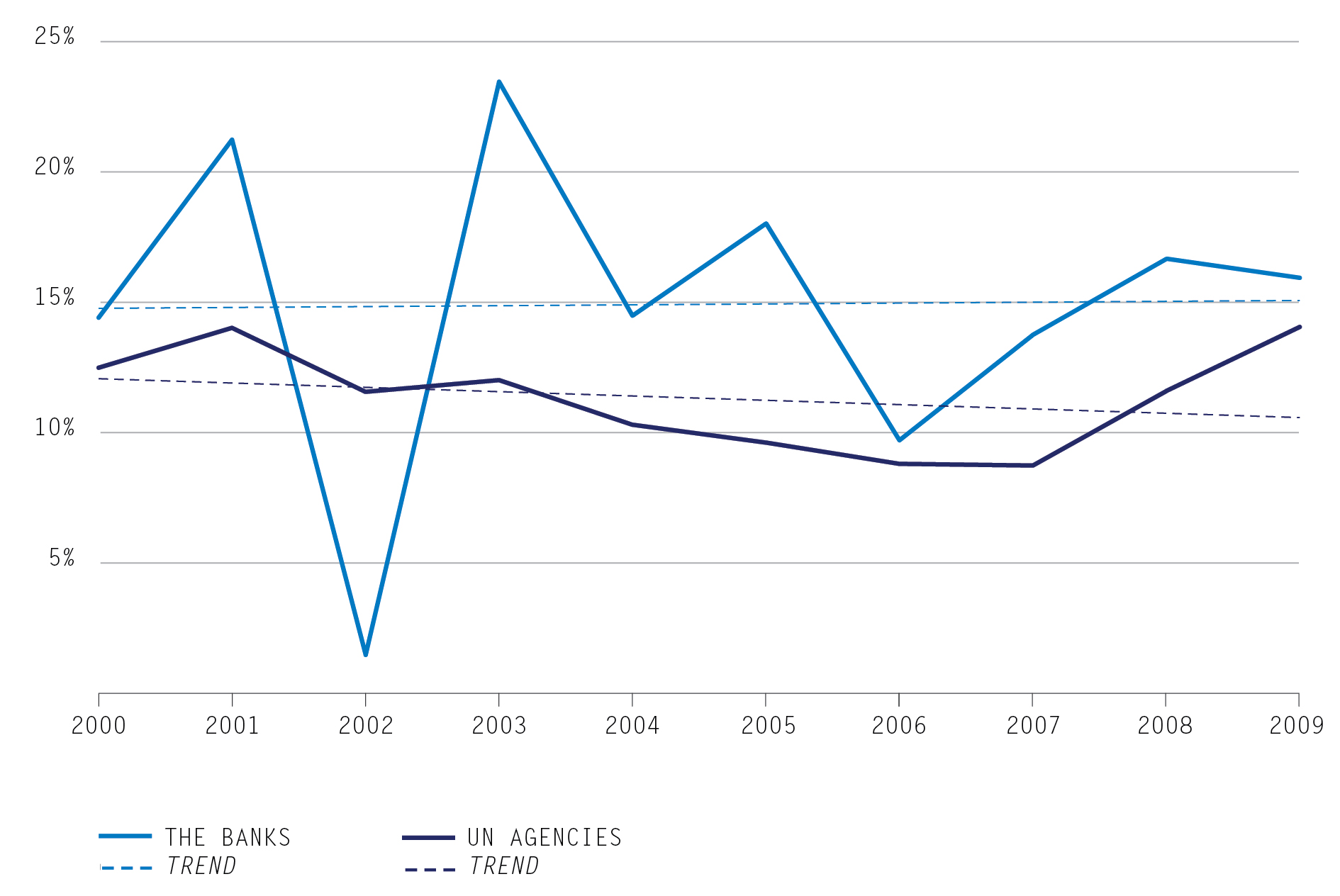

Over the previous decade, despite the overall rapid growth of the aid program, the banks claimed a steadily growing share of Australia’s aid program. Following the Independent Review, this share is set to grow more rapidly. By comparison, contributions to UN agencies declined over the decade (largely during the Howard Government), however this is also set to rise over coming years.

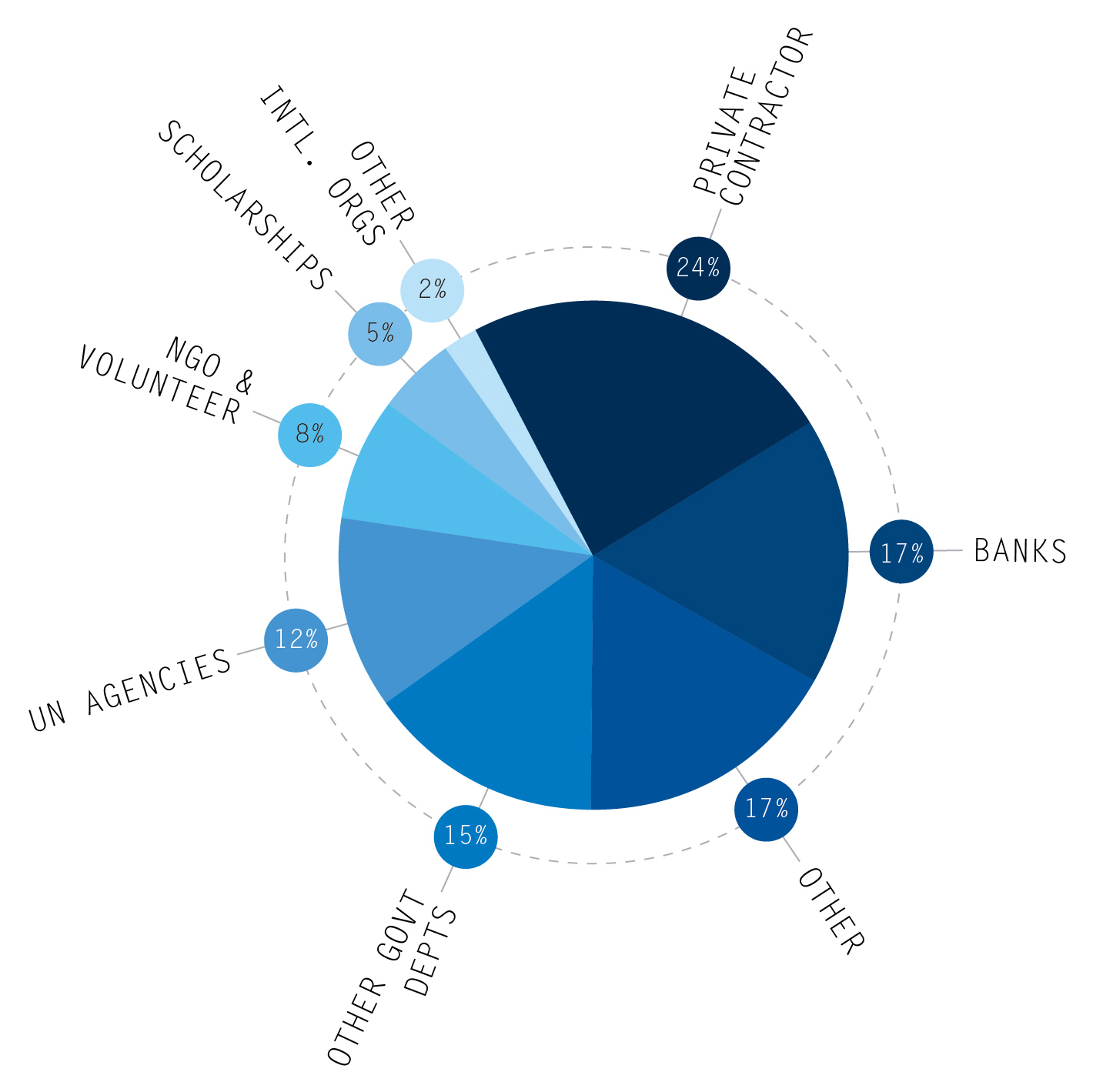

Other than AusAID itself, the multilateral development banks are the single largest channel for delivering Australian aid. In 2008, the most recent year for which there is full data, Australia delivered over half a billion ($529 million) or around 17% of its aid program through the World Bank and ADB (see graph below). In that year, only AusAID’s directly implemented programs, managed by commercial contractors, played a larger role in delivering Australian aid. Although Australia directed money to around 30 UN agencies in 2008, the overall amount of aid delivered through the UN system (12%) was not as significant as that directed to the two banks. Aid contributions directed to NGOs and volunteers in 2008 had almost doubled over the preceding two years, yet constituted less than half of that directed to the banks.

Who cares?

All this is to say that Australian contributions to the banks form a major part of the Australian aid program and they are set to grow further.

So what? These two institutions have a broad international mandate to deliver development assistance, they have an over-arching purpose to reduce poverty, they espouse a commitment to achieving the millennium development goals, and they are widely considered to be ‘effective’ and ‘efficient’ deliverers of aid.

Unfortunately, delivering aid which really benefits the poor is not that straight forward. The process of development through development assistance, is a process of intervening in complex systems of politics, economics, social structure, culture and ecology. Despite the obfuscating language of donors, development assistance is always political, always underpinned by economic assumptions, and always in danger of doing harm to the poor. In fact, it requires extreme care not to.

For well over two decades there has been a raging debate about the effect of the World Bank’s lending on poor people, and a similar debate about the ADB has been going for the last decade and a half. Those who are supportive of the banks have the dominant voice in this debate and tend to assume a modus operandi that ignores the existence of a debate at all. Nevertheless, the case against the banks is voluminous and the allegations grave.

Perhaps one way of summarising the debate over the banks is by saying that proponents tend to focus on the technical aspects of aid while critics tend to focus on the political economy of aid. Proponents, referring to the growing canon on ‘aid effectiveness,’ point to the important role the banks play in reducing the burden on poor countries of having to deal with an unwieldy number of donors. The banks are able to both coordinate and absorb a large portion of this aid, thereby streamlining the process for poor country governments. By the same token, the scale and influence of the banks, plus their use of ‘results measurement systems’, means that they are widely considered to be efficient and effective deliverers of aid. Finally, proponents point out that the banks, of all aid institutions, are the most well equipped to assist economic growth in the developing world.

For critics, it is precisely the banks’ role in attempting to catalyse growth which is a major concern. Although the banks have moved a long way from the disastrous policies of their structural adjustment programs in the 1980s, perhaps the most widespread complaint about the banks is still the extent to which their economic agenda has dominated their vision of development, and the ways in which this has shaped nearly all areas of the banks’ work, from research through to lending. There are many dimensions to this critique – such as the ways in which they have influenced trade policy, the commercialisation of agriculture, land tenure, and privatisation of utilities – however the consistent essence of complaint is that they have supported forms of economic development which tend to benefit the rich and corporations more than they do the poor.

There is no doubt that the proponents hold the ascendancy, however the criticism has been sustained and widespread. At a time when the banks are receiving unprecedented levels of funding from the Australian aid program, perhaps we should be giving this debate a little more attention.