It is early Saturday afternoon. Brightly coloured banners flutter in the breeze as shafts of sunlight squeeze their way through a darkening sky. A crowd is gathered. Anxious faces glance every now and then to the heavens, although the real object of their anxiety lies before them. A man in an immaculate black suit steps forward, flanked by a woman with tightly pulled-back blonde hair and an improbable tan. Onlookers gather at the fences and on the street. The man lifts his voice and speaks as one with authority. In carefully modulated tones, he impresses upon all and sundry the immense worth of the thing that has gathered them today. Then the chanting begins. It is a simple chanting of numbers, going up, up, always up. The tension builds to an unbearable pitch … At last! A hammer falls with shattering finality and the dark-suited Prophet cries: “Sold! To the man with the hair!”. A couple throw their arms around each other and cry with joy; someone else vomits, while yet another sobs. The rest of the crowd drift away heartbroken, like sheep without a shepherd, still in search of a home.

---

The drama of the house auction has become a common place scene in Australian cities and towns. It is such an integral part of our culture that it requires a raft of reality TV shows to help us all participate more fully in what has become a central rite of life, along with birth, marriage and death. Real estate and home renovation have become something of a national obsession; however, it comes at a high social cost. While some have found in real estate the pathway to newfound riches, many others are struggling to put a roof over their heads.

What light might the Bible shed on the ethics of the housing market and how we might behave within it? In this article, I will focus particularly on the question of how we understand ‘real estate’ and how this relates to a very important, but largely forgotten, Biblical concept known as ‘usury’. I will suggest that, in many respects, real estate has become modern usury. But it does not need to be this way. I will also suggest that the arena of housing investment is an area in which there is significant scope to think and act differently and to make a positive contribution. But first, let’s look at the current housing situation and how it got this way.

The cost of housing

It is no accident that our national obsession around real estate has come at a time when home ownership has become unattainable for more people than at any time since the end of the 1950s. In 2011, a US-based survey of international housing affordability has pointed out that Australia, ‘once the exemplar of modestly priced, high quality middle class housing’ has now become ‘the most unaffordable housing market in the English-speaking world.’

The continued and rapid rise of house prices across Australia has been one of the most dramatic phenomena of our modern history. In the decade between 2000 and 2010, median house prices in Victoria rose from $160,500 to $420,000, with sharper rises in Melbourne. While around 51% of homes sold in Australia in 2004 were affordable to ‘moderate income earners’, this had slipped to just 28% by 2012. And despite continued talk of a ‘housing bubble’, prices keep going up: by 10% on average over the past 12 months.

You don’t have to be an economist or sociologist to figure out that as stratospheric prices work their way through the system, it starts to put severe housing stress on people living on low incomes, including the whole rental market. According to Anglicare, less than 1% of rental properties advertised on the weekend of 5-6 April 2014 were affordable for anyone on a government payment. Those with complex needs, such as single parents and people with a disability, are experiencing even greater difficulty finding rental properties.

Whether you are renting or paying off a mortgage, the cost of housing is extracting an increasingly high cost from households, especially upon relationships and especially upon the marginal. But it also has implications for the church. I know of many discipleship-minded Christians, young and old, who would like to give themselves more to various forms of ministry, mission and service, but whose housing costs are forcing them to make employment choices that severely limit their scope to serve as they would like. Housing costs are also a major barrier to people trying to live more sustainably and ethically, as these choices generally cost time and money.

This is all clearly pretty unsatisfactory, but how did it get this way?

Why are house prices so high?

Contrary to what some people are suggesting, ridiculously high house prices are not the fault of Chinese investors buying up all our property. Although the surge in investment from China won’t be helping the situation, the real problem lies in the way in which Australian housing policy has been linked with wealth accumulation. I am talking here primarily about ‘negative gearing’ and the capital gains tax and how these have prompted an orgy of ‘investment’ in real estate in the past two decades.

‘Negative gearing’ is basically a policy that allows people who have invested in a rental property to write-off any losses from the cost of their interest payments against their tax bill. Negative gearing has been around in different forms for a while, but it took on a new potency in 1999 when the Howard Government halved the capital gains tax - that is, the tax you pay on any profit you make when you sell an asset, such as an investment property. Basically, this means that high income-earners can invest that would-be-tax in an appreciating asset that reaps a windfall profit when it is sold. Put baldly, if you have the means, you can either choose to pay tax or to get a high yielding real estate investment. Since 1999, this has acted like a steroid injection into the real estate market, not only increasing the number of people seeking to invest, but also significantly increasing the incentive to realise a profit through the rapid sale, and then re-purchase and then re-sale of properties.

Proponents of negative gearing have argued that it provides an incentive for investors to increase the supply of rental properties, of which there have long been too few. However, there is no evidence that it achieves this, and much evidence that it has in fact had the reverse effect. Saul Eslake, the prominent Chief Economist at Merrill Lynch, has demonstrated that real estate investors have been out-competing would be first home owners, thus pushing them reluctantly into the rental market, thus increasing the competition for rental properties, thus pushing the availability of rental properties down and pushing rents up! All in all, a grand mess.

(By the way, the combination of negative gearing and capital gains tax exemptions costs the Federal Government about $30 billion in lost revenue each year. There have been many, even amongst the mainstream economics establishment, who have pointed out that simply abolishing these two questionable tax perks would go along way to solving the government’s budgetary woes. No one in any of the major political parties seems to be listening.)

Put simply, the reason why housing in Australia is so ridiculously unaffordable is because houses have become the prime arena for profit-taking in the midst of a widespread culture of greed. Governments have encouraged this and we have rewarded them for it.

Real estate and usury

What does all this mean for how Christians think and behave in relation to real estate? Given the statement in the previous paragraph, you don’t need to be an Oxford theologian to realise that Jesus’ strong statements about greed and wealth accumulation might pose some problems for Christians joining in with the property investment frenzy. But does this mean that Christians shouldn’t own investment properties or be landlords?

Interestingly, there is a long-standing thread of Biblical ethical instruction which is usefully illuminating for the subject of real estate, but which the church has neglected for the last 500 years. I am referring to the teaching on ‘usury’. Usury is not a word in common usage anymore; however, in the Bible it refers simply to the charging of interest on loans. It is a little remembered fact that one of the central pillars of economic ethics in the Hebrew law was the prohibition on charging interest on loans, reiterated in key passages in Exodus (22:25), Leviticus (25:35-37) and Deuteronomy (23:19-20). It also becomes an important aspect of Israel’s condemnation in the prophecies of Ezekiel.

|

|

| |

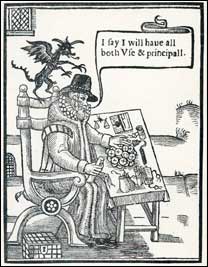

'The English Usurer' from a pamphlet in in 1634. The accompanying caption reads: 'A Usurer is not tolerable in a well-established commonwealth, but utterly to be rejected out of the company of men.' |

It is interesting to note that the prohibition on charging interest remained a central tenet of Christianity for 1500 years, up until the Protestant Reformation, a fact which we have conveniently forgotten. Surprisingly, however, the relevance of Biblical teaching on usury to modern real estate has less to do with the issue of charging of interest (the ethics of credit and debt is a big and complex subject that requires its own treatment) and more to do with what it says about paying attention to the relational nature of transactions.

Importantly, the sort of loans being envisaged in the Bible are not what we think of when we think of credit – mortgages and credit cards – rather, they are primarily loans to the poor who have fallen into hard times, such as in the case of a failed harvest. Credit in these communities is not a form of capital for investment, but rather a mechanism of the social safety net. Thus, at the heart of the Biblical horror of usury is the idea that some people might take the opportunity of someone else’s need to make a windfall profit by charging interest. It is this opportunistic profiteering that is being singled out in the Biblical condemnation of usury.

Opportunistic profiteering is precisely what is happening in the real estate market. People need housing and when there is a shortage of supply with high and rising prices (either to rent or buy), then there is little people can do but to fork out exorbitant mortgages or exorbitant rent and to try somehow to pay their other bills. To the extent that the buying and selling of real estate has become an arena for extracting maximum profits from a basic human need, then it falls under the same category of conduct as usury. It is something God’s people are called to renounce. But does this mean that Christians should not participate in investment properties at all?

Towards an alternative ethic of housing

I do not know the numbers, but there are clearly a large number of people in the Christian community who already own investment properties. There are others who, at some point in their lives, come into a large inheritance of money and for whom buying an investment property would ordinarily be one of the top options. What should they do?

Despite what has been said about the nature of the real estate market – indeed, because of the nature of the real estate market – there is significant scope for Christians who have the means, to do something creative and different, and invest in housing in ways that serve the community and/or contribute to Christian mission and ministry. But to do this requires seeing things from an entirely different perspective from the real estate market. Below are some dimensions of what it might require:

1. A new ‘investment’ ethic

In our culture, the idea of investment has become entirely captured by financial return. However, in colloquial language we do have another meaning: ‘I really invested in that group’ or ‘I really invested in that person’. What we mean when we say something like that is that we gave something of ourselves for the building-up of another. As economists will tell you, ‘investment’ is simply the relationship between the future we want to see, and the actions we take now to make that possible. At the heart of the question for any Christian then is, ‘What future do I want to see, and what part does my money play in that future?’ Generally we have been encouraged to keep these two questions entirely separate: the only future worthy of our money is to get a return of at least 7% per annum.

But what if our money became yet another means of investing in people and in good work, whether providing a service to people who struggle to get housing security or providing low-cost housing that releases others into Christian ministry, mission or just plain good work. You probably don’t need to look far to do this – within many church communities there is a ready-made mix of people who need housing and people who have it. Indeed, many of the things suggested below become much more feasible if the property is being let out within an existing community of relationships, rather than on the open market. Much of the worst behaviour in the rental market, both by landlords and tenants (and let’s remember, there are some pretty shocking tenants out there), is the product of alienated, anonymous people who bear no sense of responsibility or relationship to each other.

Importantly, investing with an alternative ethic need not abandon the criterion of remaining ‘financially sound’, however, it would not be an investment geared to the maximisation of profit. The article by Alison Sampson in this edition is a wonderful, and surprisingly straightforward example of some people making this creative leap.

2. From real estate to homes

A Christian ethic of investment requires ditching the language of ‘real estate’ and starting to talk about homes. Once we recognise that what is actually been dealt with here are people’s homes, and the profound significance this holds for the wellbeing of families, then we begin to see the weight of moral responsibility in becoming a landlord. And for the Christian landlord, there is an added significance to Jesus’ command: ‘You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant’ (Matt 20:25-26).

Practically, this means re-thinking a whole bunch of questions. Firstly, there is the question of to whom and on what basis accommodation might be offered. As suggested above, there is ample scope to be much more intentional about the provision of accommodation, but also about the length and security of the lease. In a market where 12-month leases are the norm, offering a lease for multiple years, maybe even a decade, would radically transform the experience of housing insecurity. Similarly, whereas many landlords are happy to keep bumping up the rent each year as far as they can stretch it, a Christian ethic would require re-thinking what level of rent is fair and meets your needs, rather than just what is the going rate in the rental market.

Finally, a Christian ethic requires a different level of attention to the quality of the home. I don’t mean making it fancy and modern, but making sure the amenities of the home work well, and, when there is problem, making sure it is attended to quickly and properly, rather than just cheaply. As someone who has rented for the last two decades, I can tell you that the conscientiousness of a landlord in this area counts for a lot. And we cannot these days discuss the quality of a home without including its sustainability. Does it have insulation? Is it fully draft-sealed? Are the appliances (water, gas, electricity) efficient? Currently, there is no financial incentive for landlords to consider these things and so they don’t; however, they have a big impact on the cost of living of the renter and on the ecological cost to the planet.

3. Re-thinking real estate agents

In essence, the above points are all about reclaiming the provision of housing as a relationship. However, all of that becomes very difficult when the people who mediate that relationship are entirely committed to the single goal of profit maximisation and who have a financial cut in the level of rent being charged. If the cost of rent is increasing rapidly, it is in the interests of real estate agents to make sure you keep your rent rising as rapidly as the market. Moreover, while the real estate agent has some sort of obligation to the home owner as a client, they have no such commitments to the renter. Once again, speaking as a long-term renter, the ways in which agents can use their power to ‘lord it over’ renters is one of the most unsavoury aspects of renting. Essentially, the role of the real estate agent is to keep the human relationship between renter and owner hidden and obscured from both parties. It is much easier to make money out of people that way.

I have never owned an investment property, so I should be careful here, but it seems to me there are three ways of addressing this problem:

- If you are a landlord, make it your business to know how your real estate agent is dealing with the tenants, and if need be, change agents. Come to your own conclusions about fair rent, length of lease and choosing tenants.

- If you are in Melbourne, consider using the new not-for-profit real estate agency, HomeGround Real Estate (www.homegroundrealestate.com.au).

- Best of all, if you are able, ditch real estate agents altogether and deal directly with the tenant. Once again, this is much more feasible if the property is let out within a community of relationships, rather than on the open market.

---

The story of Australia’s housing affordability crisis is a classic case study of what happens when we buy into the lie that what we do with money is somehow different from other human interactions. A good deal of the economic injustice in the world is not consciously perpetrated, but is the result of us accepting the convenient silos that allow us to keep different parts of our life – money, relationships, ethics, faith – separate. By using terms such as ‘property portfolio’, we can obscure the fact that what is being traded are homes, and, more particularly, that the type of investment in housing that has been encouraged and celebrated is making it harder for more and more families to find a place they can call home.

Reclaiming a Christian ethic in relation to investment in housing is then really just a sub-set of the much bigger task of reclaiming a Christian ethic of life. In this, as in all areas, it requires a rejection of the spirit of the age and a willingness to follow the road less travelled. It demands moving against the forces that alienate and disconnect us from each other and actively working towards restoring connection and relationship. It also requires a movement of integration, where our attitude to money and its uses is fully connected with our faith, our values, our relationships and our vocation in the world. The Apostle Paul tells us that Christ’s great work in the world is the reconciling of all things (2 Cor 5:18-19) and that we are called into this work – to invest in it with our whole lives. Surely, investing in homes is an important part of this great work.