Poverty, the Poor and the Church in Australia (Part 1)

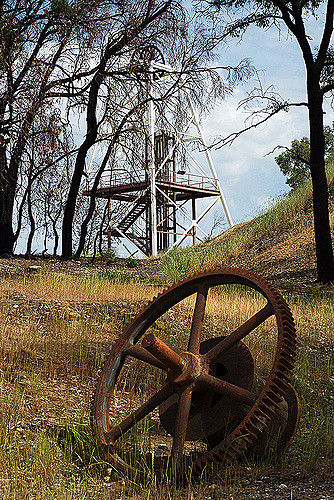

Early morning, I scramble up one of the sagging hillocks of slate that circle the west of Long Gully. They are silent now, but once they echoed to the din of huge batteries of crushers and down their dark shafts and tunnels the deafened miners crawled. The gold they extracted made Bendigo rich and turned Long Gully into a bustling township. That world is gone now.

West of Eaglehawk Road, I enter Sparrowhawk Estate, a public housing area built on ‘reclaimed’ mining land. The homes are brick, some with immaculate gardens tended since the estate was built in the late 1970s. Most of the residents are white, with a few indigenous people and a growing Karen community. Many struggle with the anxieties of insufficient income, debt, illness, disability, unemployment and stigma. Some carry the added handicap of abusive parents who cared little and more whose parents didn’t know how. They share with wealthier neighbourhoods a mix of personalities: the vindictive, the forgiving, the compassionate and the cold-hearted. What they don’t share is the stress of poverty; that in the land of promise, they have failed. As William Stringfellow said, ‘Where money is an idol, to be poor is a sin’. Like many ‘sinners’, some have turned to salves to make the shame and boredom bearable: drugs, alcohol, violence, crime. But others live heroic lives: caring for sick family, fostering nieces and nephews rather than allow them to enter the dubious system of child ‘protection’ and giving hours of service to their neighbourhood.

The people of this neighbourhood are often referred to by terms such as ‘battlers’ or ‘the marginalised’, or ‘those experiencing disadvantage’; but in the biblical lexicon they are ‘the poor’. How do we make sense of the Bible’s teaching about ‘the poor’ in relation to the real people and the real places we encounter? Who are the poor? What defines the experience of poverty? Who are we in relation to the poor and who are we together?

This is the first in a series of articles trying to grapple with some of these questions. It is an exercise in situating myself within a larger story: both the story that we inhabit as Christians and the story of Long Gully. This is my neighbourhood and it is the ground from where these reflections spring. Later articles will delve more deeply into the experience of disadvantage in contemporary Australia, look at what divides us from ‘the poor’ and, finally, ask most pointedly, where is the Christian church in all of this and where should it be?

What story are we in?

I met Robbie a decade ago. Robbie’s mother died when he was 11 and from then his elderly grandmother cared for him. Robbie had an intellectual delay and rarely attended school. Robbie’s grandmother died two years later. His uncle, though he cared deeply for Robbie, could not support him. Robbie was soon in trouble with the police and spent time in youth detention. Too young, he became a father and soon his children were taken into foster care. He is young, jobless, with scant education and mountains of anger and grief. His story is not strange in Long Gully.

What should we do about this? Stanley Hauerwas writes:

Morally speaking, the first issue is never what we are to do, but what we should see. Here is the way it works: you can only act in the world that you can see, and you must be taught to see by learning to say.

If we can only act in the world that we see, and we learn to see by saying, then we need to say our story. The first story is that of the reign of God, whose central and defining character is Jesus Christ. When Christians see poverty, we do not first see a problem of policy, social structures or personal values, but a problem of our identity as Church, the body of Christ. The second story is that of the places where we find ourselves, the places where we must somehow live out the story of Jesus.

Seeing the image of God

What is our story? As I have wrestled with these essays, I find myself trying to paint a fair image of my neighbourhood that is true to the hardship, yet does not harden the crust of demonisation. When I look to Jesus for clarity, he points not to simple explanations, but to God’s glory revealed in the midst of poverty. The poor in Long Gully are not obvious examples of ‘everlasting splendours’ (as CS Lewis put it) and it’s tempting to put them on a pedestal against the slanders they daily suffer. But for every person ennobled by poverty, dozens are diminished. Poverty has not been kind to Robbie.

Yet God insists that the poor are vehicles for glory. Think of the story of the blind beggar in John’s Gospel (John 9:1-41). ‘Who sinned that this man is blind?’ The disciples' request for a villain is rebuffed: ‘He is blind that the glory of God may be revealed’. Jesus’ statement messes with our verities about poverty. Surely, there must be something to blame; either his own sin or his family’s or social injustice. Such is the way that we attempt to resolve the trauma of poverty - find a villain and then relax, safe in the knowledge that nothing is required of us. As the Pharisees say, ‘Surely we are not blind, are we?’

But maybe something is required of us. Maybe our task is not to solve poverty, but to take to heart Jesus’ prophecy that ‘you will always have the poor among you’. The church will always be the companion of the poor, never desiring poverty’s extension or existence, but simply to be friends of God and friends of the poor, in the pattern of Jesus and in the power of the Spirit. As Dorothy Day knew, the task is personal and spiritual. Jim Forrest, her biographer, learnt this from her:

The most radical thing we can do is to try to find the face of Christ in others, and not only those we find it easy to be with but those who make us nervous, frighten us, alarm us or even terrify us. ‘Those who cannot see the face of Christ in the poor,’ she used to say, ‘are atheists indeed.’

Perhaps that is where the glory is revealed. We all bear the image of God and the Church’s task is to see that image in all, to seek out those who have not been treated as image-bearers. The Church is to be a present sign of the future promise of the Reign of God, where all people are seen and loved and known as they really are - as image-bearers of God.

The story of Long Gully

| |

The gold rush of the 19th Century made Long Gully a busy place and some of Long Gully’s children grew to be significant people in Bendigo and Australia. Long Gully boasted many successful sporting teams, a vibrant fire brigade and an active civic culture.

But the gold ran dry, its promise stretching out beyond the fingertips of the technology available. Along with enormous wealth, gold had created a large population of fatherless families as miners died painfully from phthisis, a vicious disease caused by inhalation of the silica dust that filled the mine tunnels. The land also suffered: countless trees were cut down to feed mining machinery and for construction. By the turn of the 20th century, poverty already existed in Long Gully. In 1907, The Bendigo Independent reported on the Long Gully Aid Society, and quotes Miss Rowe, a member of the Society:

We help everybody, irrespective of what denomination they belong to...We find out where people are in distress and relieve them. For instance, some people may not be able to purchase firewood and when we find that out send a load round, have it placed quietly in their backyard, pay the man and say nothing about it.

Such charity is typical of the time, when church people went into battle against poverty. One of these was F. Oswald Barnett, whose passion for social reform found its target in the ‘slums’ of inner city Melbourne. Historian Renate Howe comments that ‘Barnett drew on a Christian Socialist tradition in Methodist theology...Barnett criticised the church for not asking enough: ‘What’s wrong with society? Why haven’t we the brotherhood that Christ preached?’‘. In the wake of the Great Depression, which halted much construction and created a housing shortage, Barnett was appointed as a Commissioner of the newly created Housing Commission of Victoria (HCV).

The HCV had an ‘environmentalist’ philosophy: transplant the poor from slums to suburban comfort and they would improve in physical and moral health. The HCV demolished the worst slums and encouraged home ownership through low-cost loans. However, the HCV’s focus on social welfare shifted after World War II: the surge of European migrants and returning soldiers led to a housing shortage and the purpose of the HCV became less about the poor and more about those who needed a house. Gradually, the problem of lack of housing shifted onto the ‘market’ rather than the government and, once again, housing policy focussed on those with low incomes.

| |

This is a common image of Long Gully in the media, but is it the real story? |

This resulted in Sparrowhawk Estate predominantly being tenanted by the poor. At the same time, globalisation began to bite. In October 1979, Latrobe University published a report by Dr Paul Langley which showed a serious slump in jobs in Bendigo: for young men aged between 15-19, the jobless rate in Bendigo was 33.2%. John Fisher, who ran the Bendigo Community Youth Support Scheme (CYSS), said that:

Sparrowhawk Estate, and other Housing Commission areas, really need work done on them among the unemployed…If anyone did a survey on unemployment in the Sparrowhawk estate, you would find it much higher than even Dr Langley’s survey, which is really frightening.

From the very beginning, Sparrowhawk Estate was filled with people who suffered the stresses of poverty, along with the realisation that the one road out of that life (a stable job) was becoming blocked. In short, it contained a recipe for a host of social problems. This is not to say that Long Gully is only a tragic place. But it is simply to say that the troubles of my neighbours do not come from a void, but that they have a history which gives them depth and colour.

---

The task of saying our stories, both biblical and historical, is a key discipline of the people of God in places of hardship and poverty. Saying these stories keeps them in our mind’s eye, steering us away from solutions based on illusions, both about our world and about our own capacity to change that world. The task of memory keeps our feet on the ground as we encounter our neighbours; an experience as disorienting and painful as it is hopeful and heart-warming.