2008 was a momentous year for humanity. While the affluent world was preoccupied with the Global Financial Crisis, three other events of perhaps even more moment were taking place. In that year, a food crisis was gripping the developing world, leading to food riots in over thirty countries across three continents and playing a role in igniting the Arab Spring, of which the conflict in Syria is an ongoing legacy. Although some of the drivers of the food crisis were a coincidence of so-called ‘cyclical’ factors, the larger part was driven by the deeper structures of the global food system that sounded an ominous note for the century to come. Another great event of moment in 2008, so UN demographers tell us, was that humanity became an urban species, with over half the population of the planet now located in cities and that figure growing inexorably towards 75% by 2050. And finally, 2008 was also the year that world leaders dropped the ball on climate change, setting the cause of decarbonising the economy back by years.

These were not unrelated events. The financial crisis, the food crisis and climate change are all symptoms of a global economic system that is tearing apart the fabric of human community and natural ecosystems. And the throbbing engine of this economic system are cities, those great behemoths that suck in people, resources and even human souls (Rev. 18:13) and spill out their waste upon the planet.

What do these great affairs have to do with the humble world of local churches and faith communities? If we take seriously Paul’s proclamation that we are being called as ambassadors of Christ’s work of reconciling the world (kosmos in the Greek), then it suggests that we need to think about cities not merely as contexts for our mission, but as subjects of our mission. Cities are not just canvasses upon which we are painted: they are complex systems and structures that shape human relations with each other and the earth, and they can do so in highly destructive ways. Can we envision urban structures and systems that are not destructive, but wholesome and nurturing? Can we work for the shalom of the city in ways that take the structures of the city itself seriously, and not just the individuals found within cities? To do this we first need to have a clearer view of the problem.

Seeing cities clearly

From its origins in ancient Sumer, the city has been an expression of humanity’s struggle to achieve insulation from nature. It emerges from the shadows of pre-history already defined by intensive exploitation of nature, economic specialisation, social stratification and the centralisation of violence and authority. But even the earliest city-civilisations cannot be understood by looking merely within their walls, for these cities were predicated on the reorganisation and control of their hinterland and by long-distance trade. Their food was grown to a large extent, although not exclusively, by people who were not residents of the city but were nonetheless under its thumb, and scarcer resources came through networks of trade, primarily with other cities that were reorganising and controlling their hinterlands.

Fast-forward to the twenty-first century and the map of the world-economy is little different. Our habit of drawing the map of the world according to the political divisions of nation-states has obscured the fundamental structure of economic power that undergirds human history. If we were to map the flow of goods and money in the world today, it would reveal, in effect, a network of interconnected urban centres, each drawing in resources from their hinterlands, distributing them and increasingly concentrating them through a hierarchical chain of regional, national and global cities.

Thus, whenever we are looking at economic inequality or exploitation, or at despoliation of nature through over-exploitation and pollution, we are primarily considering the economic effects of cities. But, some will object, the greatest single driver of our planetary ecological crisis is the destruction of habitat and release of carbon into the atmosphere that has come as a result of land conversion for agriculture and not from cities. This is true, but the particular form of agriculture that has done this damage is precisely that which has been called into being by the demand of cities.

In the modern era, cities have entered into a new phase. Right up until the mid-nineteenth century, London - then the apex global city - still fed itself overwhelmingly from its hinterland of the Home Counties and, to a surprising extent, from urban agriculture within its own bounds. It was in the second half of that century that London grew beyond that possibility, drawing in grain and meat from Ireland, North America and Australasia. This also solved the problem of supplying cheap food to low-wage industrial labourers upon which modern urbanisation was predicated. With the spread of industrialisation and industrial agriculture in the twentieth century, and facilitated by new technologies in transport and storage, there have now grown up a series of monster cities around the world which can no longer live off a hinterland, but which instead have become dependent upon the planet.

|

|

The story of Babel is a potent symbol of humanity's ongoing project of ‘self -creation’.

|

But here I have only described the material and sociological aspect of the city; what about its spiritual aspect? Jacque Ellul, in his classic work, The Meaning of the City, has masterfully described the spiritual essence of the city as rooted in humanity’s stubborn project of ‘self creation’; that is, our ongoing effort to define ourselves apart from our creator. ‘Just as Jesus Christ is God’s greatest work, so we can say, with all the consequence of such a statement, that the city is man’s greatest work.’ And just as sociologists read cities as attempts at insulating humanity from nature, so Ellul (via the Bible) reads cities as attempts at insulating humanity from God. Thus, we find in both the material and spiritual structure of cities, forces that are continually working to separate people from God, from each other and from creation. In other words, the city as a structure and a system has been characterised by forces of disconnection.

It is not surprising, then, that the Biblical text is full of prophetic denunciations of cities - Babylon, Nineveh, Tyre, Sodom and, not least, Jerusalem. What is shocking though, is that although the city represents the culmination of man’s choice, man’s work and man’s rebellion, God nevertheless says ‘yes’ to it. In a move that pre-figures the incomprehensible grace of God’s movement towards us in Christ, God enters Jerusalem and makes it holy. Thus, alongside all of those denunciations of the city, we also find in the Bible a host of wonderful visions of the city as she ought to be, the city as a place of shalom. Within the Biblical vision, the redeemed city, the holy city, is a force for peace in the world and brings harmony and economic security to its rural hinterland:

For out of Zion shall go forth instruction and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He shall judge between many peoples, and shall arbitrate between strong nations far away; they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more; but they shall all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees, and no one shall make them afraid; for the mouth of the LORD of hosts has spoken. (Micah 4:2-4)

Even more strikingly, and more directly relevant to our own missiological context, when the exiled people of God find themselves in the archetypal fallen city - Babylon, the great enemy of God - they are instructed to live lives that are manifestations of shalom and to work and pray for the shalom of Babylon itself (Jeremiah 29:1-7).

What would a vision of shalom look like for today’s cities? If we take seriously the material and sociological structure of cities, and the underlying spirit this expresses, what would it mean to live for, work for and pray for shalom in a modern city?

Cohesive Territorial Development: a new urban possibility?

Given what I have said above about the material and sociological structure of cities, it is not surprising that the UN-Habitat’s World Urban Campaign declares that ‘the battle for a more sustainable future will be won or lost in cities’. Central to the ‘new urban agenda’ being promoted by the World Urban Campaign is the idea of ‘cohesive territorial development’. Recognising how cities have dominated and shaped physical spaces and social structures, they seek to direct the city’s power over space and place towards more socially and ecologically positive development. This requires having a comprehensive perspective of how people, places and resources are being treated and utilised within the entire spatial zone that a city draws on, including its hinterland and beyond. It is an ambitious agenda:

The City We Need coordinates sectoral policies and actions, such as economy, mobility, housing, biodiversity, energy, water and waste, within a comprehensive and coherent territorial framework. […] The City We Need is a catalyst for sustainability planning across jurisdictions within the region it occupies. It actively seeks to coordinate and implement policies, make investments and take actions that retain local autonomy while building and enhancing regional cooperation. It actively seeks cross-sectoral coordination and cooperation and promotes mutually beneficial and environmentally sound linkages between rural and urban areas.

It does not take great prophetic imagination to realise that this statement represents a secularised vision of urban shalom. There is a strong recognition here that ‘human wellbeing’ - which may be as close to a spiritual idea as is possible in a secularised context - is bound up with the material structures of our life, the nature of human community (or lack of) and the ecological health of the planet. In essence, it is articulating a need for overcoming the systemic disconnection that characterises the structures of urban life. It would not be going too far to suggest that the cumbersome language of ‘cohesive territorial development’ is really a grasping for a vision of healing and wholeness, if not quite of holiness.

What might cohesive territorial development mean, then, for how we think about urban mission? Surely, if we are to think about cities not just as contexts for Christian mission but also as subjects of Christian mission, then we need to be thinking about this sort of subject matter. Unfortunately, despite bearing a Biblical story that is characterised by wholism - a story that continually makes the connection between the spiritual and the material, the individual and the communal, the human and the non-human - Christian mission has at times been guilty of a certain narrowness of vision. True, William Booth’s observation that no one ever got saved with a toothache has been taken heed of, and a great deal of mission these days seeks to address, in some way, material needs as well as spiritual needs. However, Christian mission has rarely taken notice of the fact that those material needs take place within the context of economic systems, has taken even less notice that those economic systems take place within the context of ecological systems and hardly ever is it recognised that economic systems are in themselves spiritual forces.

So what might Christian mission learn from cohesive territorial development and in what way might we contribute to it? The scale of the challenge it poses is daunting, calling for cities ‘to coordinate very diverse agendas related to land use, housing, energy, water, waste, mobility, health and education, economic development and the promotion of gender equality, cultural vitality and social inclusion’! And despite the confidence of the World Urban Campaign that ‘new predictive planning and modelling tools based on systems approaches’ will make all this possible, it is hard not to feel that the task of comprehensive territorial development might become a technocratic black hole. Nevertheless, the ‘new urban agenda’ in which this vision is couched calls for the involvement of not just the multiple levels of government, but also civil society, academic, business and grass roots organisations and even affirms the principle of ‘subsidiarity’ (the devolution of responsibility) stemming from Catholic social teaching. How might we locate Christian communities and mission work within this mish-mash?

Jeremiah’s letter to the exiles in Babylon provides a helpful hint. The task of comprehensive territorial development is huge and, let’s be honest, the role that Christian communities play in most cities is tiny. Nonetheless, just as Jeremiah asked a small, marginalised and powerless community to contribute to the shalom of the great city-empire through the vehicle of their homes, gardens, families and communities, so, too, Christian communities should have an appropriately humble and realistic appreciation of their own social location within cities and yet still feel they can have some sort of life-bringing leavening influence. Contributing to the shalom of the city must therefore firstly begin by working with what we have and where we are; and, secondly, it must involve working in partnership with others beyond the bounds of our own communities and faith. Let’s consider each of these in turn.

Working towards healthy neighbourhoods

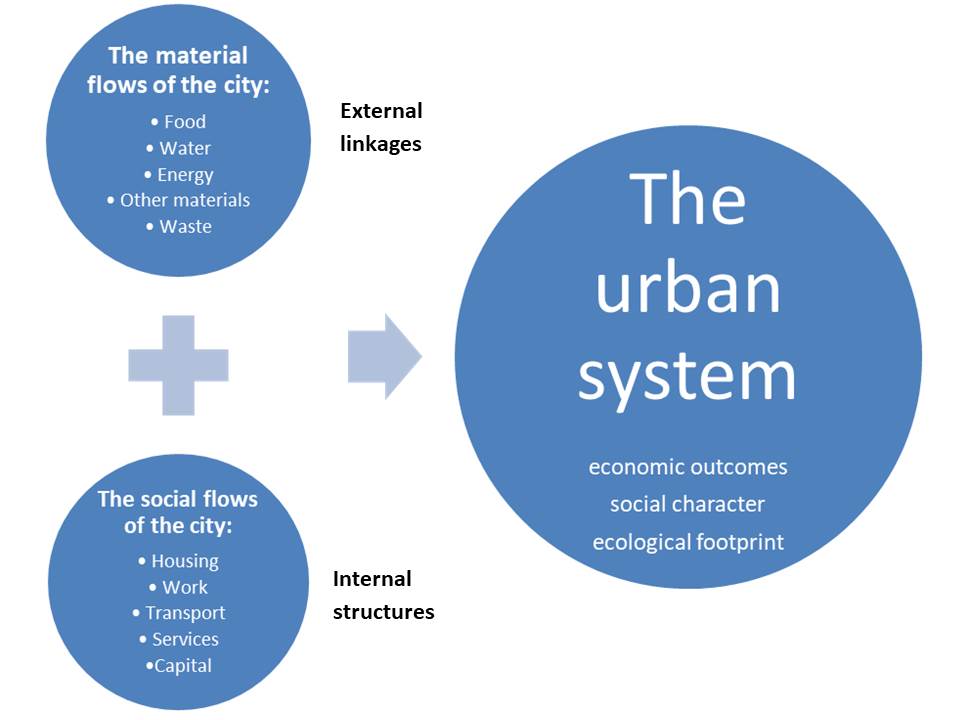

If the structures of the city tend towards disconnection, then a key missiological task for Christian communities within cities must be to seek re-connections. The language of comprehensive territorial development is a bit too grand, cumbersome and technocratic to be of much use in mission; however, its core ideas can nonetheless be enacted in very practical ways at the local level. The essence of this new urban agenda can be described more straightforwardly as working towards healthy neighbourhoods, where the ‘health’ of a neighbourhood is holistically understood to include its material, social, economic, communal, spiritual and ecological context. In practice, this means paying attention to the fundamental elements of life in the city, paying attention to the dis-connections between these elements and paying attention to how these disconnections manifest in our neighbourhoods.

It may be helpful at this point to simply map out what those key elements look like:

As has been said above, it is clearly inconceivable for most Christian groups to work at the system level; however, when these elements are translated down to the neighbourhood level there is an abundance of possibilities. Take, for example, the Casa de Videira community in Curitba, Brazil. Here, a small Christian group has made the connection between the ill-health caused by modern Western diets, especially amongst lower socio-economic groups, the ecological damage caused by industrialised agriculture and by urban food-waste and their own disconnections from creation, meaningful work and good food. In response, the community has undertaken to make a series of re-connections, via their own labour, collecting organic waste in their immediate neighbourhood and growing food using that waste. Claudio Oliver, pastor of the community explains:

Eating is connected with our treatment of the dejected and rejected - the leftovers. Our major concern, as Christians living in the city, is how the relationship with food in the city reveals our neglect of creation. Every day, tons of nutrients arrive, are delivered, cooked in the city and more than 30% of it is wasted. Every day, we collect organic waste in a 3 kilometre radius from our homes: gardening clips, grocery stores greens, leftovers, wood chips and ground coffee. We collect three to four tons of organic garbage a month - the refuse of roughly 150 households - and compost it all in our 0.08 acre back yard, turning it into beautiful soil. From this we produce around three tons of organic vegies per year and feed 25 chickens, 4 goats, 30 rabbits, giving us protein in the form of meat, eggs and milk. All this provides food for ourselves and our neighbours, shared every day in a communal meal.

In the western suburbs of Melbourne, a group of Christians have begun a social enterprise that specialises in re-using, recycling and even up-cycling office waste and e-waste, at the same time providing employment opportunities for the long-term unemployed and welfare dependent (see May 2018). In my own community, the Seeds Community in Bendigo, we have recognised the connections between the social dysfunction of welfare-dependent families, the behavioural issues of their children, their physical ill-health and their dependence on cheap, unhealthy, highly-processed foods. By providing an open community garden, basic cooking classes, a people’s pantry and a kids' garden club, the church has opened avenues of relationships with broken families who have complex needs. The role that the church plays in their lives is still small, but it is simultaneously material and spiritual.

Indeed, the potential connections that can be made between food, waste and employment at the local level are huge. As has been mentioned above, the modern city is a peculiarity to the extent that it has excluded food production from within its bounds. Within an increasingly volatile global food system, the door is opening for a re-emergence of urban agriculture that offers simultaneous opportunities for improving urban nutrition, providing employment and decreasing greenhouse gas emissions (through the composting of food waste and reducing food transport). When Cuba’s oil-dependent agriculture was suddenly thrown into crisis in the 1990s, the spontaneous rise of organic urban agriculture - by necessity rather than design - was able to supply 80% of the fruit and vegetables of Cuban cities. In Detroit, a city crippled by deindustrialisation and ‘white flight’ to the suburbs, there has been an efflorescence of vacant lot gardening that has been supported by marketing cooperatives, community health care and youth training.

.jpg) |

|

|

These developments are all characterised as small-scale, bottom-up, grass roots ventures and, as is evident from the examples above, Christian communities are often well placed in terms of skill sets, energy, a ready-built cooperative structure, and access to land, to play an entrepreneurial role in supporting and stimulating such ventures. In the US, the New Parish Movement has been building a network of churches and Christian groups who are beginning to see themselves in just such terms. They talk of ‘refounding church in the everyday context of the neighbourhood’, rooting it in a locality and linking it to the real needs of the community.

The founders of the movement have gone one further and launched a Neighbourhood Economics network that seeks to attract ‘social investment capital’ into supporting grassroots local ventures. While the nexus between food, waste and employment is perhaps the most readily exploitable opportunity in such a neighbourhood approach to mission, it is not hard to imagine that by leveraging more of the under-utilised (or poorly utilised) capital within churches, Christian communities could play similar roles in the development of local business ventures, local renewable power generation and water harvesting and distribution projects, especially in developing countries where the urban poor are chronically underserved in terms of energy and water.

Working in partnership

If we have an appropriately humble and realistic appreciation of the social location of Christian communities within cities, and if we appreciate that seeking re-connections is critical to their missiological task, then these two things suggest that Christian communities should embrace the opportunity to work in partnership with groups and bodies who do not share their faith convictions.

Let me stress that I am not here suggesting that we adopt a version of secular pluralism which blandly assumes that differences in values and worldviews are irrelevant.

Rather, where we have identified in concrete and practical terms various ‘goods’ that will contribute to the health and wholeness of our neighbourhoods, not only does it make good sense to work with others who have also recognised those goods, but many of those goods will simply not be achievable without cooperative action. For example, we do not need to share all of the same ideological convictions of a particular environment group to recognise that working towards more local renewable energy is a good thing and that it makes good sense to work together towards such a goal. In doing so, we are likely to discover that we actually share some deep loves, which in turn will help us to more clearly and more kindly understand our differences.

In my hometown of Bendigo, the Cornerstone Community, has played a not insignificant role, punching above its weight in catalysing a ‘regional food alliance’ between the municipal council, the local university, local businesses and various community groups. These groups clearly represent a diverse range of interests and ways of working; however there is a simple common recognition that strengthening the local food economy brings with it a range of economic, ecological, social and nutritional benefits. The fact that a local Christian group has played a role in hosting (within a church!) some of the key meetings of this coalition has the potential to tie together these concerns with an awareness of a deeper wholism and charitable spirit that it can only be in the interests of Christian mission to foster.

As the World Urban Campaign has recognised, the particular and urgent demands of the ecological crisis, the food crisis and various other modern malaises are beyond the scope of governments alone to address, but rather require cooperative action across government, business and civil society. In particular, there is a need for a whole host of commonsense policies around food, waste, water and energy that will only come through the political lobbying of coalitions. It is time for Christian groups to lose their squeamishness for working in such partnerships, where we can identify common goals. As theologian Luke Bretherton has suggested, working in partnership amid diversity expresses a grace and Christian hospitality that need not sacrifice the distinctiveness of the Christian vision.

---

The crises of the twenty-first century are characterised by a series of disconnections: the spiritual from the material, the economic from the ecological, the urban from the rural, food from the soil, the individual from the community, and the soul from the body. Cities, as the definitive form of human organisation, represent these disconnections in their most intensive form. In many ways, the city is characterised by humanity’s disconnection from God. The scandal of the Biblical testimony is that God is yet willing to work with humanity, to take what they have built in their rebellion and to bring healing and wholeness to it. The great challenge and vocation that is given to God’s people is to be a people who live, work and pray for the shalom of the city, no matter how marginal they may be.

The agenda for cohesive territorial development laid out by the World Urban Campaign in many ways approximates a secular vision of shalom, working towards re-connection of multiple spheres of community, locality, economy and ecology. It is a program for which Christian mission should feel a certain affinity and, as such, should be prepared to work in partnership with and even, humbly, to accept guidance from. In many ways, the health of Christian faith into the twenty-first century will be dependent upon its ability to re-connect the multiple spheres of life under a single, coherent vision of the gospel.