Finding Life in Jesus’ Hard Teachings on Money (Part 3)

|

|

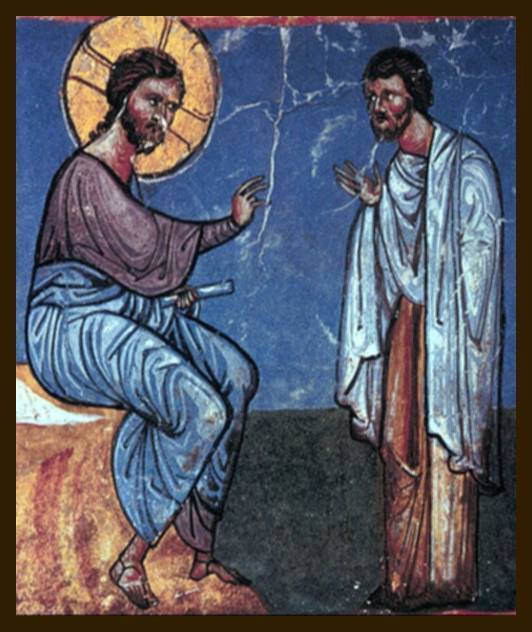

| Jesus and the rich young man. |

So far in this series we have been looking at Jesus’ teachings on money and paying attention to just how counter-cultural and difficult they were. The underlying premise has been that although everyone finds Jesus’ teachings hard (and I mean everyone), once we plumb their depths we find something profoundly life-giving; something that is not only good for the world, but also good for us.

As I have often said in this newsletter, the whole meaning and purpose of Jesus can be summed up by that short statement, ‘I came that they might have life and have it in abundance’, and this statement can and should be applied not just to our own little lives, but to the whole Community of Creation. Jesus' teachings on money should always be seen as a subset of this great purpose.

As we shall see, the core teachings of the New Testament about money revolve around the concrete practices of renunciation, generosity and contentedness. As with so much of the teaching of Jesus, these practices are commended to us for deep and broad reasons – they are simultaneously concerned with limiting harm, accomplishing good in the world and with personal liberation. In the great economy of God, there is no conflict between such things. The great question is how we enact such things in a complex global economy and hyper-consumer culture. To such territory we will turn in the next article in this series, but we are not there yet. We still have one more obstacle to be cleared away.

If Jesus' teachings on money are meant to be life-giving, why would he go and say something so polarising as ‘Woe to you who are rich’ (Lk 6:24)? This is perhaps one of the most evaded texts of the gospels and certainly a candidate for the gospel text least preached on from the pulpit. Why would Jesus say such a thing? Is he really just some sort of ancient angry communist?

When approaching this declaration of woe to the rich, much depends on what sort of tone of voice we imagine Jesus speaking in. Was it the sort of righteous accusation you might hear being shouted down a megaphone by a Socialist Alliance agitator, or was it spoken slowly and quietly, with anguish and earnestness? We don’t know, but we can guess. Mark’s gospel tells us pointedly that when Jesus spoke to the rich young man looking for the secret of eternal life, he looked at him ‘and loved him’ and so advised him to sell all he owned, to give the money to the poor and then to ‘come, follow me’ (Mark 10:21). In Luke’s gospel, when the super-rich Zacchaeus undergoes a life-changing transformation, Jesus joyfully declares: ‘Today salvation has come to this house … For the Son of Man came to seek out and to save the lost’. It is clear that Jesus is no anti-rich ideologue – when he says ‘Woe to you who are rich’, he is saying something we need to hear, not a message of condemnation.

We also need to be very clear about how our own position as readers/hearers shapes our response to a text like this. Do we enjoy this instance of Jesus sticking it to them (the rich)? Or do we squirm at the uncomfortable prospect that Jesus has denounced us? So let’s get one thing straight: when Jesus is talking about ‘the rich’ in the gospel, by any standard that is meaningful, he is talking about us. One of the most enduring gifts of my time working in Laos and Cambodia is that it is now impossible for me to evade the fact that I am immensely wealthy. Although our family is in the lowest 20% income bracket for Australia, we nevertheless live luxuriously, forming part of the elite top 10% of income earners in the world (see ‘How do you rank?’ in Manna Matters, May 2015). I am reasonably confident that this also applies to most Manna Matters readers.

Although Luke’s gospel is the only one that records Jesus saying ‘Woe to the rich’, there are a plethora of teachings across the New Testament (indeed, the whole Bible) which warn about the perils of wealth. Foremost among them, of course, is Jesus’ anguished observation to his disciples as he watched the grieving rich young man (whom ‘he loved’) depart from him: ‘How hard it is for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God’. There is also the letter from the Apostle James which strikes a very similar note to Jesus: ‘Come now, you rich people, weep and wail for your miseries’ (James 5:1). Not to be outdone, the Apostle Paul writes: ‘But those who want to be rich fall into temptation and are trapped by many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil, and in their eagerness to be rich some have wandered away from the faith and pierced themselves with many pains.’ (1 Tim 6:9-10). And then there is the message to the church of Laodicea in the Book of Revelation: ‘You say, “I am rich, I have prospered, and I need nothing.” You do not realize that you are wretched, pitiable, poor, blind, and naked.’ (Rev 3:17).

There is a lot going on in all of these texts, and each one warrants its own exposition. However, for our purposes, it is also critical to realise that there is an essential unity to the teaching of the New Testament on the matter of wealth, and that is a teaching that puts all of us in 21st Century Western civilization in an awkward position. Woe to the rich. How hard it is for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God.

What, then, could these warnings about the perils of wealth mean for us who are wealthy and yet would be followers of Jesus? There are two dimensions to these teachings that need to be considered.

|

|

| Lazarus and Dives. |

Firstly, just as many fear, there is indeed an element of judgement to these teachings. This is particularly clear in the letter of James: ‘Listen! The wages of the labourers … which you kept back by fraud, cry out, and the cries of the harvesters have reached the Lord of hosts. You have lived in the earth in luxury and in pleasure; you have fattened your hearts in a day of slaughter’ (James 5:4-5). Judgement is also central to the story of Lazarus and ‘the rich man’ in Luke 16.

In both these cases, there is a strong association between the existence of wealth and the fact of injustice, and, indeed, this is a very strong theme throughout the Old Testament too. Although not all inequality is the product of injustice, there is little doubt that the vast chasm of global inequality in which 20% of the world’s population consumes 80% of its resources is by and large the product of endemic and systemic injustice. Australian affluence today cannot be explained without beginning from the monumental fact of stealing a continent from its indigenous possessors. The cheapness of consumer products today – whether coffee, clothing or computers – cannot be explained without including the environmental negligence of so much large-scale mining and agriculture and the appalling work and wage conditions in much of the developing world, often literally involving the withholding of workers’ wages, who surely still cry out to heaven.

The Bible is consistently clear that God is outraged by such things. This is the proper meaning of the ‘wrath’ of God – not that God is a harsh and angry deity, but that he quite rightly is outraged when humans treat each other inhumanely. He does not remain neutral about such facts, he makes a judgement about them. As the texts from James and Luke and so much of the prophets make clear, God takes sides. We should rightly feel uncomfortable about our implication in global structures of injustice.

Judgement is a difficult and uncomfortable concept, and one that has frequently been misconstrued when reading the Bible. When we ‘judge’ someone, it very often means that we have written them off – we do not permit them scope for an alternate possibility outside of our estimation of them. We must not imagine God’s judgement is like that. The word that is most often translated as ‘judgement’ in our New Testaments is the Greek word krisis, from which we get our word ‘crisis’. In the Bible, judgement is a time when things come to a head, when God makes clear where he stands. Yes, it is a scary and confronting moment, but other than the idea of ‘a final judgement’, which is beyond our scope to discuss here, God’s judgement in the Bible is primarily an opportunity for change. God’s judgement of us is always a function of his love for us. It is indeed true that every crisis is a moment of opportunity. As Abraham explains to the soul of the dead rich man in Luke 16, the witness and judgement of the prophets was present in his life continually to permit him an opportunity to choose a different path.

And that is where judgement leads into the second dimension of the Bible’s warning about wealth, which is God’s concern for the wealthy. As I have said, the whole meaning and purpose of Jesus can be summed up in one verse: ‘I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly’ (John 10:10). But what are the things that get in the way of us ‘having life’? In the diagnosis of Jesus, money and wealth is one of the primal forces that lure humans away from ‘the life that really is life’ (1 Tim 6:19).

Let us look at the evidence. Since the end of the Second World War, real incomes in Australia have more than trebled, yet studies have confirmed again and again that there has been no gain in happiness whatsoever. This finding is eerily the same across all wealthy developed countries, irrespective of language and culture. In fact, in the last two to three decades, when wealth increase has been most rapid, there has been an alarming rise of symptoms that point to a deep malaise at the heart of our wealthy culture. Most prominent has been the breakdown of that which is most foundational to human wellness and thriving – relationships. This is reflected in the frighteningly high rates of family breakdown, but also in the incredibly high rates of people reporting a sense of isolation. Equally as prominent, and surely linked, is the dramatic rise in mental ill-health, especially depression and associated conditions. And then there is the phenomenon, surely also linked, of lifestyle diseases (obesity, diabetes, heart disease, renal failure): as drugs and medical treatment continue to increase our longevity, our way of life is making us increasingly unwell.

What we are witnessing is not just instances of social, mental or physical unwellness that have afflicted this person or that person; we are witnessing a culture that is deeply unwell. All of us are affected. And we are putting our finger right on the heart of the matter when we describe this culture as an affluent consumer culture. It is deeply focussed around the gratification that comes from the consumption of things and therefore it is organised around money. Mammon really and truly is an idol of immense spiritual power (see ‘Unmasking Mammon’, Manna Matters, May 2015).

But there is one more symptom which has been noticed far less, but which lies at the heart of this whole existential crisis. All the evidence points inexorably to one striking fact: the wealthier we have become, the harder it has become to believe in God. We all know about declining church attendance since the 1960s and the end of ‘cultural Christianity’ (not quite finished yet) is probably a good thing. Much more concerning is the rate at which genuine Christian faith is being transmitted – or rather, isn’t being transmitted – from parents to children. Also concerning is the deep theological, ethical and existential uncertainty being expressed by many who believe and are trying desperately to hold on to faith. You don’t have to live in a big house or drive an expensive car to be affected by this – it is in the very air we breathe.

It is no accident that the loss of God has come at the same time as the triumph of Mammon. How hard it is for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God. In his famous Parable of the Sower, Jesus describes three archetypal barriers to faith and the third one rings particularly ominously for us: ‘As for what was sown among thorns, this is the one who hears the word, but the cares of the world and the lure of wealth choke the word, and it yields nothing’ (Matt 13:22). Truly, we are the generation amongst the thorns.

Why do we have so much trouble with this concept? It is a truth that has been almost universally acknowledged amongst all the great religious and philosophical traditions of the world, it is one of the most basic understandings of folk wisdom and it is something which most people (if they are honest and reflective) have some evidence for in their own lives.

Why does Jesus say ‘woe to you who are rich’? Let us listen to his answer: ‘because you have received your consolation’ (Lk 6:24). In other words, because we get what we want. It is the tragedy of the human condition that so often what we think we want is not what gives us life; we are tempted towards gratifications which end up doing harm to ourselves and to others. It is the curse of the rich that we are able to give fuller expression to such temptations.

And there is a yet deeper implication. The rich – that is most of us in the affluent western world – receive ‘their consolation’ (what they want) through their own power, which is the power of the money they hold. This means they are easy prey to the great deceit that they are self-sufficient, that they do not need God. In a previous article, I stated that this was the core deceit at the heart of the spirituality of the city – that humanity can fool itself into thinking it is self-sufficient – but it is equally the power that money has over us too. Indeed, cities and money are, excuse the pun, two sides of the same coin. This is the core dislocation of humanity that Genesis describes and its effects ripple out into all of the vast social injustices and ecological depredations that we can see today. Self-sufficiency equals independence which equals separateness which winds up as aloneness; and aloneness, as the Bible teaches, is another word for death.

The scandal of the gospel is that the road to life – ‘the life that really is life’ – runs in a different direction from the one we most often choose when left to do what we want: ‘for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life’ (Matt 7:13-14). That is why Jesus confronts money and wealth so directly and so forcefully. It is one of the primal forces that creates division and the promotion of self against the other, when the very thing that gives and sustains life is the communion of love. In the Bible, love and life are almost interchangeable. That is why Jesus says, ‘If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves …’ (Mk 8:34).

It is from these core teachings about ‘the path that leads to life’ from which Jesus’ teachings on money flow. The monetary practices that are commended in the New Testament – renunciation, generosity, contentedness – are not hoops for us to jump through; they are not spiritual exercises that demonstrate the extent of our faith. Rather, they are the practical mechanisms by which the power of Mammon can be broken and we rich can be saved from ourselves. It is to these that we will turn in the next edition.