You can see those mighty kings sitting in state on their thrones,

robed in luxurious purple, surrounded by glittering armour, …

but only take away their raiment of vain splendour

and you will discern the festoons of heavy chains that bind them.

See the lust in their hearts, and observe their poisonous greed. ... Their sorrows gnaw within them,

and their boundless hopes torment them,

helpless and wretched victims.

The kings are overthrown; the rulers are ruled by these masters.— Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, IV.2

On the morning of Friday November 28, 2008, over 2000 people were gathered outside the doors of a Wal-Mart store in Long Island, New York, awaiting its opening. Many had been there since the previous morning, lining up for the annual Black Friday sales.

A 34-year-old Wal-Mart employee, Jdimytai Damour, was tasked with opening the doors of the department store. As he did, the horde of shoppers surged inside, breaking the doors and, according to a witness, leaving the metal part of the door-frame crumpled like an accordion.

As they poured through the entrance, the shoppers knocked Damour to the ground, walking over him as he lay there. Other workers attempted to rescue the man, but they were trampled. Several of them were injured in the scrimmage. Damour was killed.

When Wal-Mart officials informed customers that they were closing the store on account of Damour’s death, shoppers complained—many of them in a vitriolic fashion—that they had lined up for a long time for the Black Friday sales. The vast majority continued to go about their shopping.

What might explain this kind of frenzied and barbarous behaviour, the ravenous and irrational striving for luxury material goods? What might account for the senselessness of a young man being sacrificed in the pursuit of discounts on televisions and toasters?

This kind of behaviour isn’t innate. It’s something that is learned, absorbed from some cultural context. That context, I would suggest, is consumer culture.

Consumer culture as our context

It is no exaggeration, I think, to say that consumer culture has shaped us into a people who have almost no limits on our desires. Those of us in the West—and increasingly in the rest of the world—have imbibed the idea that nothing we want is bad, so long as it doesn’t harm another person (or, at least, so long as we aren’t aware of that harm).

When I say ‘consumer culture’, I’m talking about the culture formed within the context of consumerism. Consumerism is distinct from, say, mere consumption, the necessary act of using resources. Instead, consumerism refers to our current economic and social order that incites the endless acquisition and accumulation of material goods. For champions of this order, a person’s well-being and happiness depend on such accumulation.

‘Consumer culture’ is what results from this economic and social order: the culture—the particular beliefs, values, norms, and behaviours—in which the meaning of our lives is mediated through markets, such that we become known primarily as ‘consumers’.

Desire: The engine of consumer culture

At the heart of consumer culture is desire. Desire is complex and varied, but can be defined, in simple terms, as a disposition toward something. A central and crucial driver towards the constant accumulation of goods in consumer society is the creation and moulding of people’s desires, the turning of our dispositions toward certain things. Such is achieved in a variety of ways, both technical (so-called ‘planned obsolescence’, for example), as well as social and cultural (such as advertising and ‘perceived/continual obsolescence’).

The notion of ‘creating’ desires might seem odd to some in our current age. After all, we live in a time when, according to philosopher Charles Taylor, people think,

Everyone has a right to develop their own form of life, grounded on their own sense of what is really important or of value. People are called to be true to themselves and to seek their own self-fulfilment. … No one else can or should try to dictate this content’ (Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity, p.14).

We might assume that we are in control of what we desire, that it’s a matter of our own choices and freedom. But what we come to value isn’t manufactured in a vacuum. What we think is important, and much of what we desire, is developed in a social and cultural context. In other words, we aren’t as free or as in control as we assume we are.

The organised creation of dissatisfaction

Certain desires are obviously triggered by biological and physiological cues—hunger, thirst, etc.—but others arise contextually. If this weren’t the case, advertising would be fairly pointless. Advertising has, however, been hugely successful in shaping what it is that people desire.

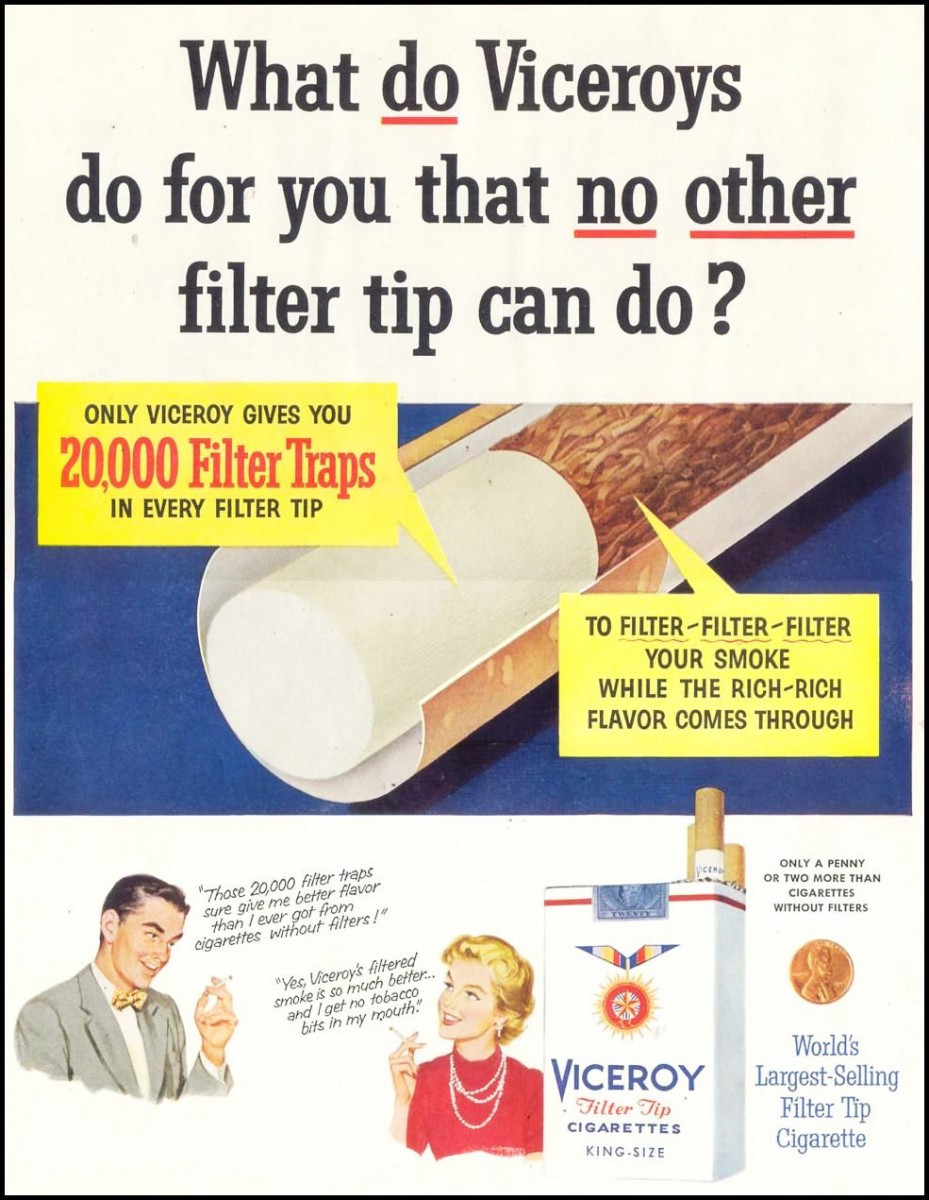

|

|

|

An example of Rosser Reeves' 'unique selling

proposition'.

|

Early advertising was rather simple, often outlining the benefits of a product in the hope that people might see its value and be convinced to purchase it. By the 1930s, however, things had shifted; advertising executive Rosser Reeves introduced the ‘unique selling proposition’, where the focus was on how a product might solve a customer’s problems. In 1935, George Gallup pioneered market research, the gathering of information about people in order to more effectively advertise to them. Things have only escalated from there, with digital superpowers like Facebook and Google having many dozens of data points on each of their users.

The logic of contemporary advertising is simple: what Charles Kettering of General Motors called, ‘the organised creation of dissatisfaction’. One of the more recent results of this logic is the phenomenon of ‘pornification’. While, strictly speaking, pornification refers to the mainstreaming of porn culture (consider how this is altering the desires of young people, especially boys, making them feel dissatisfied with ‘normal’ sex), pornification can also be applied to other forms of consumption. Whole trends and careers have sprung up around ‘food porn’, ‘travel porn’, and ‘exercise porn’, whose provocative and hyper-real images are ubiquitous on social media platforms such as Instagram.

One of the achievements of such a ‘pornified’ lens on the world, a lens through which the world is pictured in unrealistic terms, is the creation of dissatisfaction. Our lives, after all, do not look like that. Such dissatisfaction inevitably leads to a desire for such idealistic things—things that transcend the apparent drudgery of daily, embodied life.

|

|

|

Pornification: food, travel, exercise, sex.

|

An unbearably delectable culinary dish. A painfully beautiful Mediterranean sunset. An inhumanly chiselled torso. An unachievably erotic sex act.

We rarely notice the dissatisfaction this system creates. After all, consumer culture thrives on the façade of fulfilling our desires; if we could see through its smoke and mirrors, we would hardly be hypnotised by it. But the contradiction is that this system, which promises to satisfy our desires, only ever produces dissatisfaction. And regardless of how much we consume in this system, our desires are never gratified. This is entirely intentional, since our satisfaction would mean consumer culture’s demise.

And so, this consumerist system rolls on, leaving a trail of greenhouse emissions, devastated landscapes, ocean garbage patches, starving mouths, broken bodies, and hungry souls.

Looking for God in all the wrong places

We should, however, be cautious before too readily condemning people for buying into consumer culture. This is true for at least two reasons. First, we are all implicated, albeit to varying degrees. Second, it is entirely natural for people to get caught up in consumer culture.

Why on earth would I make this second claim? Surely consumer culture is anything but natural.

Here we would do well to recall St. Augustine’s words in the opening to his Confessions: ‘You (God) have made us for Yourself, and our hearts are restless till they find their rest in Thee’. For Augustine, all of our desire, all of our longing, is ultimately for God, the source of all goodness. Sometimes, however, our desires go awry, and we end up pursuing lower things. But even then, in the midst of this or that form of idolatry—in the worship of things lower than God—we are ultimately seeking to satisfy our desire for the Creator by way of created things.

Created things, as Augustine said, contain traces of the Creator. When seen in their proper, ordered place, created things can become the means through which we enjoy God. Creation is, after all, ‘good’ (Genesis 1) and through it we can enjoy the Source of all goodness. When seen out of place, however, created things can become an end in themselves, through which we seek to placate our existential yearning for God.

This is why capitulating to consumer culture is entirely natural, insofar as doing so is to attempt to reach the transcendent, the very thing for which we were created. In a sense, consumerism is a form of spirituality. But, by seeking the transcendent in the material, we end up constantly disposing of the material since it never lives up to our desires.

The result, as William Cavanaugh notes, is not attachment to things, but detachment. We constantly purchase new things, but our attachment is only ever being short-lived before we sense our own dissatisfaction and move to the next thing. In truth, we are not necessarily too materialistic, but rather we are not materialistic enough; we don’t truly embrace the gifts of the material world, but rather dispose of them as failed idols in our search for transcendence.

The gospel alternative to consumer culture

We don’t really need climate change to exist in order to know that consumer culture is harmful and anti-Christian. If we had properly recognised the state of our desires and their proper ends, the Church may have embodied an alternative to consumer culture long before the urgency of global environmental ruin forced itself on us.

What, then, might be the imperative of the gospel in light of consumer culture?

If I’m correct that consumer culture constitutes a form of worship directed at things other than God, we must disentangle ourselves from it. This is, however, easier said than done. Participating in our extrication from consumer culture is, as I have argued, not simply a matter of rational decision-making. The genius of modern marketing is such that our rationality and autonomy are overridden (see Crisp, ‘Persuasive Advertising, Autonomy, and the Creation of Desire’). We have formed deep-seated habits—patterns of thought and behaviour that direct countless of our daily decisions—and much of the time we are not overtly aware of them. What, then, can be done?

Playing around the edges of the problem, changing a few odd behaviours, will not be sufficient to revive the witness of the Church in the midst of consumer culture. Consumer culture has taught us to desire without limit. There needs to be change at the level of our desires, at the very core of who we are. Daunting as this may seem, the Church has always had the resources to do this.

One starting point might be to recover the practice of fasting. It used to be that fasting was a regular part of the Church calendar, even a weekly or bi-weekly occurrence in some traditions. Why was this the case? Is fasting a way to earn spiritual merit? By no means. Fasting was—and is—an expression of the fact that learning to become more like Jesus is not a matter of good intentions, nor automatic sanctification. To become more like Jesus, and to embody the gospel in our lives, requires training.

Fasting is a form of training. It is an act of learning to overcome our self-centredness. Fasting is the act of abstaining from the object of some desire—food, comfort, whatever—so that we refuse to let that desire control us, learning to master it rather than allowing it to master us. It teaches us detachment, though not from the world, as Thomas Merton said:

We do not detach ourselves from things in order to attach ourselves to God, but rather we become detached from ourselves in order to see and use all things in and for God (New Seeds of Contemplation)

In other words, those who fast learn to detach themselves from their selfish desires, so that they may be attached to God. Moreover, those who fast learn to control their desire for simple things, like food and comfort, so that they can learn to master their higher, spiritual passions—greed, list, envy, anger, and so forth.

-copy.jpg) |

|

|

The Temptations of Christ, 12th century mosaic at St Mark's |

Jesus in the wilderness in Matthew 4 and Luke 4 is a helpful model here. In this story, we see that even Jesus needed to fast; fully human, he needed to master his desires. When the Tempter, the Satanas, finally confronted him after forty days, offering the means to satisfy his desires (provision of food, public legitimation, rule over the kingdoms of the world), spiritual strength gained from fasting meant Jesus could assert that the devil’s word was not God’s word, that the devil’s way was not the way of the kingdom.

The presence of ‘the Tempter’ takes many forms in our time, and it may be that fasting and praying, as well as humble gratitude for what we have, are the practices of which the Church is most in need in order that we might resist consumer culture and offer an alternative to it.

Another necessary practice to help us overcome our detachment might be, as Cavanaugh notes, ‘to turn our homes into sites of production, not just consumption’. This imperative of reviving the ‘home economy’ has been a staple message of Manna Gum for a long time, so I won’t wade too deeply into it at present.

It is worth saying, though, that we desperately need to see through the veil created by consumer culture whereby the human, animal, and environmental costs of our economic system are separated from us. Indeed, they are quarantined away so we may consume without guilt or responsibility. Reclaiming our home economies constitutes part of our being awakened to the truth, since it involves recognising the effort and the cost that goes into many of the things we take for granted. Such may help us jam a stick into the spokes of our more thoughtless desires and habits, and may also reshape how we interact with the material world.

There are, of course, many other gospel-inspired imperatives in the face of consumer culture, from rethinking work to political action. I am convinced, however, that the most pressing issue is the formation of a people—the Church—who will learn to desire differently and, in doing so, will together become a living alternative to consumer culture.

Dr. Matthew Anslow is the editor of Manna Matters and a lecturer at Morling College in Sydney. He's married to Ashlee and together, with their three young children, they live at Milk and Honey Farm, two hours west of Sydney.