It’s 4am, but you don’t know it yet. You reach for a glass of water beside the bed. Then for whatever reason you also have to know what time it is. Your hand fumbles across the side table for your…

It’s 10am. Bi-weekly team meeting. Someone hasn’t turned off their…

2pm, walking back from lunch, you sense something’s missing. You clutch an empty pocket. Stomach drops, conversation ends abruptly as you dash back to the café for your…

It’s 4pm and the kids have been patient and easy-going all afternoon. Now they’re starting to get a little ratty and disturbing your conversation. To gain a little peace and quiet you hand them your…

9pm and you’re squirming as you watch your favourite thriller. You allay some of the piercing discomfort with a quick look at your…

11pm and it’s another day done and dusted. Only one thing left to do: plug in your…

---

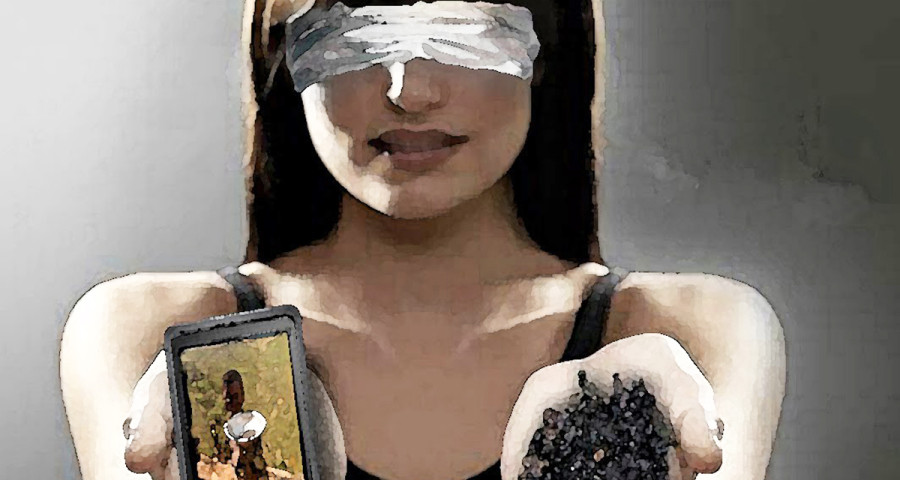

Alongside the most mundane of life’s titbits can sit the most significant realities of the world we live in today. In the most routine moments of existence, there are threads that lead to the most profound.

Our phones constitute one of those mundanities which, when examined more closely, tell us many profound things about ourselves and our world. Each of us has a link, via our phone and many other of our electronic devices, to one of the most horrific and yet ignored situations of violence and destitution in the world today.

Inside your smartphone, your TV, your internet modem, your laptop, your tablet, your smart fridge, is an intricate set of chips which perform a vast array of functions, some of them bordering on quantum scale. The intricate functions performed by the motherboards within these devices require very finely controlled power levels and this is where tantalum capacitors come in.

A capacitor is a simple manager of electrical flow. Capacitors can be made from many different materials, but one of the most reliable and longest lasting is a metal called tantalum. Tantalum sits at number 73 on the periodic table. It is a chemically inert metal that can be used as a substitute for platinum and is regarded as a ‘Technology-Critical Element’ by the US Department of Energy for its use in a wide range of technologies..

Tantalum is commonly mined in the form of coltan, but it can also be produced from the by-products of tin mining and derived from recycled e-waste. The world’s biggest single producer of coltan in 2013, the last year for which there are reliable figures, was Rwanda. Second was Brazil and third was the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Both Rwanda and the DRC have a chequered past, and the fact they produced, between them, over 40% of a ‘Technology-Critical Element’ justifiably raises concerns. In recent years, Rwanda has taken great strides towards peace, democracy and wellbeing, partly funded by regulated mining activity.

|

|

The DRC has also made progress in some areas; however, in many situations, it is clear that unregulated, clandestine mining activities and exports have fuelled a conflict and humanitarian crisis on a scale never before seen. While the DRC’s civil wars, triggered by a spillover from the Rwandan crisis of the late 1990s, are technically over, conflict persists, where rape is used as a weapon, child labour common and health outcomes dire.

The conflict in the DRC, raging since 1996, has been the deadliest single conflict since World War II. This superlative is so common when one hears—if one hears—about the DRC that perhaps it doesn’t carry so much weight any more. But if you take pause to consider that so many people have died in a single conflict within a single country that it ranks second only to World War II it begins to sink in. And when you consider the relative importance of the DRC in the nightly news, compared to, say, the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, the absurdity of it all begins to hit you.

There are approximately 4.5 million internally displaced people in the DRC. Imagine the population of Melbourne forcibly displaced, forming chaotic and disease-ridden encampments across the countryside, preyed upon by militias and people smugglers. These people have been displaced by an unceasing epidemic of violence. It is estimated that there are over 140 armed groups active in the eastern provinces of the DRC, battling for territory and the proceeds of whatever profitable activities are still able to take place there. One of the most profitable of those is mining.

The links between mining and conflict have a long history in the DRC. Seventy-five percent of the copper used in the brass shell casings of allied troops in World War I was Congolese. As was the uranium used in the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When it comes to the league tables of national mineral deposits, the DRC is a heavyweight. It has significant reserves of cobalt, copper, diamonds, tantalum, tin, gold, coltan, uranium and lithium. Overall estimates of the DRC’s mineral wealth sit at around US$24 trillion.

This potent mix of money, corruption, lawlessness, poverty and conflict is at the heart of the crisis in the DRC and mining is the catalyst. Under President Joseph Kabila, approximately US$4 billion disappeared from the national accounts every year. In 2013, 8 to 12 tonnes of gold, worth about US$400 million, disappeared. And in a 2016 plea bargain in the US, it was disclosed that a US hedge fund paid more than US$100 million in bribes for mining concessions worth several billions of dollars. Clearly there is something very wrong here.

Attempts have been made to address this vicious cycle. In 2012 , the Obama administration passed a bill that included laws relating to ‘conflict minerals’. This concentrated minds at many large technology companies, including Apple and Samsung, which have taken steps towards greater knowledge of their supply chains and greater disclosure of that knowledge. Perhaps the most significant of these is a requirement by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for yearly conflict minerals reports, which are publicly available. Apple directed suppliers to stop using five refineries and smelters which refused or were unable to comply with a conflict minerals audit. In 2017, Amnesty International praised Apple and Samsung for their efforts in tracking and eradicating conflict minerals from their supply chains.

Clearly it is possible to improve practices, and the leadership exists to make such practice common. However, in that same year, the Enough Project published an extensive ranking of companies, primarily tech and jewellery, with most of them falling far short of a reasonable ethical standard. To its credit, Apple was lauded for continuing to source minerals from the Congo, but from mines that had been third-party audited and approved as benefiting the local community.

Present-day DRC reflects back on us an image of our society and global economy that is complex, convoluted, conflicted and consumption-obsessed. It is a country of 70 million sitting at the heart of Africa that goes largely ignored, but which is hugely exploited. The challenges faced by ordinary Congolese in the quest for a safe, fulfilling life are enormous.

In Australia, as citizens of one of the wealthiest countries on Earth, where 88% of the population owns a smartphone as well as a plethora of other electronic devices, we are inextricably linked into this global system and to the exploitation of the DRC.

There are bright spots, however, as the issue of conflict minerals gains momentum and technology companies take their responsibilities seriously. Much remains to be done and if we must purchase electronics it pays to do our research [see box below]. Awareness can feel like a burden, but it need not be. We cannot individually solve anything, but if we each do our best and raise our collective awareness, we bear witness, and in so doing we learn to be part of the solution to the unjust systems in our world.

Tom Allen lives and works in Geelong, where he runs a social enterprise bike shop and lives in an intentional community of urban farmers and permaculturalists.

Responsible consumption of electronic devices1. Buy fewer gadgets. Upgrade less often. Try doing without some things altogether (gasp!). 2. When a device is broken, look into repair before replacing. Find out if there is a 'repair cafe' in your local area. 3. Seek to source devices second-hand before buying new. There is a huge array of high-quality electronic stuff available on Gumtree, eBay and from social enterprises like Green Collect.

4. When buying new, check out the Shop Ethical Guide or website to see which brands are accredited for conflict minerals. www. ethical.org.au 5. When disposing of unusable devices, make sure they go to an e-waste recycler. Check with your local council to find one. |