Spring 2020. Prohibited from gathering inside, Melbournians rediscovered city parks and gardens. Clusters of picknickers reclined on the grass, savouring food, drink and companionship. In some parks, white painted circles adorning the grass reminded picnickers to ‘social distance.’ This Spring was unusually wet and warm. There was a great deal of grass.

****

We most often hear the stories of Jesus feeding large crowds as told by Matthew (14.1–23; 15:29–39), Mark (6:34–44; 8:1–10) or Luke (9:10–17). Yet, it’s only in John’s account of a miraculous feeding that we encounter “a great deal of grass.” Several other details are unique to John. Only John reminds us that the Sea of Galilee is the Sea of Tiberias (6:1) and tells us that Passover is approaching (6:4). Only in John do we learn that the loaves are barley bread (6:9, 13) and hear Jesus speak of “the bread of life” the following day (6:26-38). Let’s revisit the story as John relates it (6:1–15).

After this Jesus went to the other side of the Sea of Galilee, the Sea of Tiberias (6:1). Herod Antipas constructed the city of Tiberias in 18 CE, strategically located on the South West shore of the sea to facilitate taxation of the fishing industry. He named the city in honour of Caesar Tiberius, emperor of Rome between 14 and 37 CE. Only Luke identifies Caesar Tiberius by name (3:1); none of the Gospels mention the city given his name. Only John mentions the imperial name for the sea, using it only in the stories of the miraculous feeding (6:1, 23) and, post-resurrection, the miraculous multiplication of fish (21:1).

Before Passover, five thousand plus people resting on a great deal of grass eat their fill of bread and fish. After Passover, seasoned fishermen are surprised by a phenomenal catch. Idyllic scenes? Perhaps if viewed in isolation. But John evokes the shadow of empire with a name: Tiberias. This is Roman-occupied Palestine, highly militarised, increasingly monetised, ruthlessly taxed. John reminds us that these feeding and fishing miracles took place in a world in which the realities of empire drove anxieties about daily bread, depleted fish stocks and eroded livelihoods. The Sea of Galilee was the Sea of Tiberias.

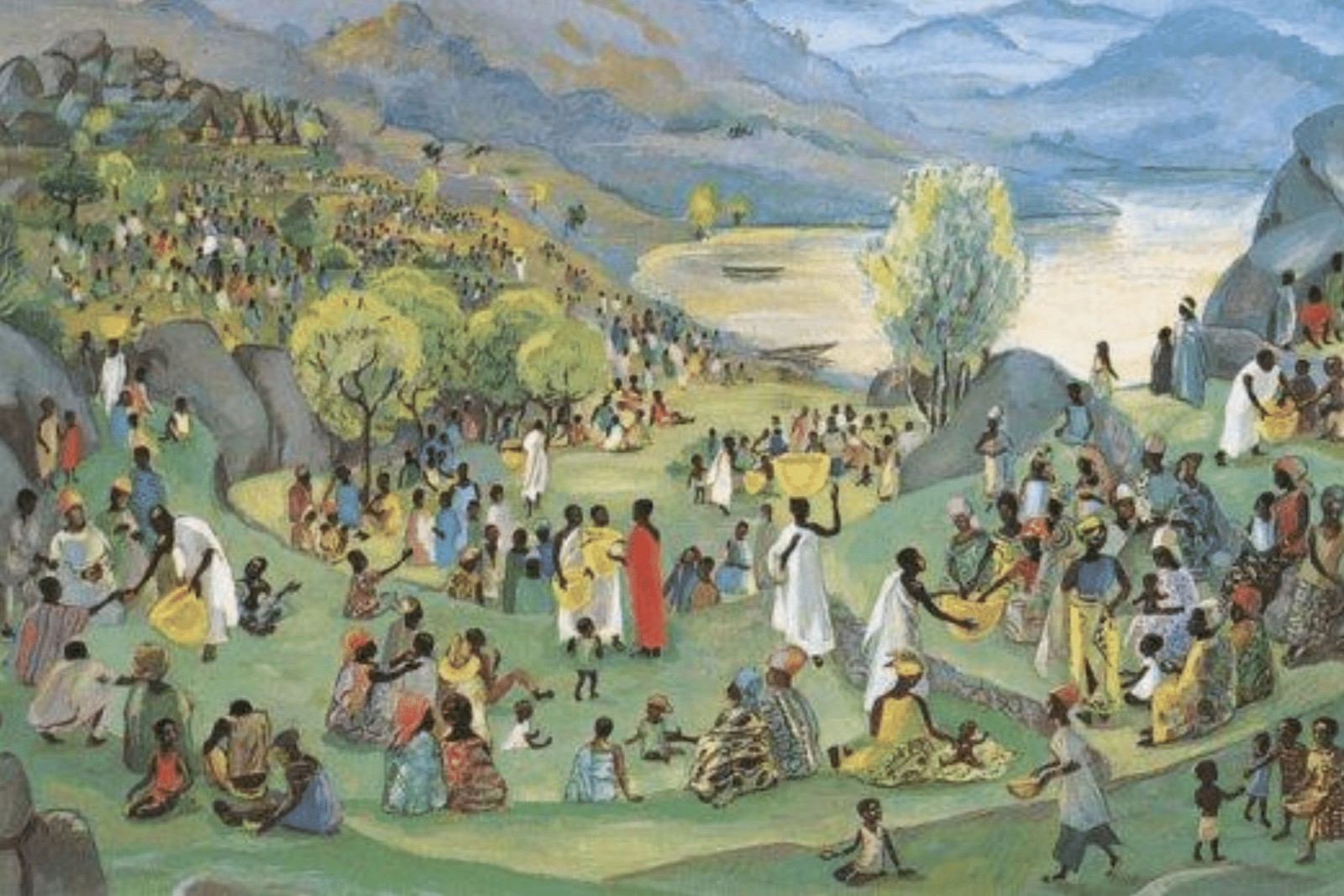

Jesus Mafa, Cameroon 1973, Vanderbilt Digital Library

A large crowd kept following [Jesus] because they saw the signs that he was doing for the weak. Jesus went up the mountain and sat down there with his disciples. Now the Passover, the festival of the Jews, was near (6:2–4). Observant Jews celebrate Passover by remembering and re-enacting their liberation from slavery in Egypt, the giving of the covenant, and God’s miraculous provision of manna, bread from heaven, and quail—meat—in the wilderness. At the time of Jesus’ ministry, descendants of those freed slaves still lived in the Promised Land but were no longer free. Herodian, Roman, and ruling priestly demands fell heavily on the population. Everything was taxed: fish, fishing boats and fishing nets, salt and yeast, grains and breads, even barley and barley bread, the basics of life. The land still flowed with milk and honey—there was a great deal of grass—but they no longer enjoyed its fruit. Rome, like Egypt, was an economy that enriched a few and impoverished many. Passover calls imperial pretensions into question, nourishes hope among the oppressed, and reminds us that God is a God who acts to liberate: the way things are is not the way they will remain.

Seeing the crowd approaching, Jesus asked Philip, “How are we to buy bread so that these people might eat?” He said this to test him, for he himself knew what he was going to do. (6:5–6). Jesus’ words echo a question Moses asked during the first Exodus: “Where am I to get meat to give to all this people?” (Num 11:13). Whereas Moses’ used the language of gift, Jesus tested Philip with the language of market exchange. Literally, “How are we to market bread so that these [people] might eat?”

Philip answered him, “Two hundred denarii would not buy enough bread for each of them to get a little.” (6:7). A denarius, a Roman coin bearing Caesar’s image and inscription, was the coin with which each adult Jew rendered the annual head tax to Rome. Its monetary value was roughly equivalent to the amount daily labourers received for a day’s work if they found work. Two hundred denarii was more than most families saw in a year. Philip instinctively assumed a transactional market-based response. He focused on scarcity, on what was lacking. He assumed that there would not be enough.

One of his disciples, Andrew, Simon Peter’s brother, said to [Jesus], “Here is a boy who has five barley loaves and two small fish. But what are they among so many?” (6:8–9). Although troubled by the arithmetic, Andrew draws attention to resources already present among the crowd. He does not assume a transactional market-based response nor focus on scarcity, on what is lacking.

The five loaves are barley bread; the fish are small. Barley bread was the staple food of those who could afford nothing else. A first century Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria, considered barley bread “highly questionable,” fit only for consumption by “animals and unfortunate humans.” A Roman historian, Pliny the Elder, and the Jewish historian, Josephus, thought much the same. Barley bread was rough and plain, simple fare, the bread of the poor.

Loaves and Fishes, John August Swanson

Jesus said, “Make the people sit down.” Now there was a great deal of grass in the place and they sat down, about five thousand in all. (6:10). A great deal of grass, an abundance of grass, grass that sprang from the ground when rains fell in season, grass that grew without human cultivation or calculation. The plentiful grass evokes the Psalmist’s testimony of God’s provision: “The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want. He makes me lie down in green pastures; he leads me beside still waters.” (Ps. 23:1–2).

Then Jesus took the loaves, and when he had given thanks, he distributed them to those who were seated; so also the fish, as much as they wanted. (6:11). A boy (or a slave or a child, the Greek is not specific) offered what they had: five barley loaves, two small fish. Jesus blessed, literally eucharist-ed, the food and distributed it. How would those five barley loaves and two small fish feed the crowd of thousands? It was not immediately obvious. The food multiplied as it was distributed, as it was shared.

When they were satisfied, he told his disciples, “Gather up the fragments left over, so that none may be lost.” So they gathered them up, and from the fragments of the five barley loaves, left by those who had eaten, they filled twelve baskets. (6:12–13). Living in contexts where food is too often wasted, we easily lose sight of how amazing it was for people to eat as much as they wanted, until they were satisfied, and still to have food left over. The barley bread was precious as well as abundant; they gathered the fragments that none might be lost. Those who live with hunger know better than to throw leftovers away.

|

|

|

Maciejowski Bible, 13th century |

The gathered fragments of barley bread remind me of an Afghan proverb: Rez-e-non om non ast. Even a fragment of bread is bread. Bread has a special place in Afghan culture. It is holy, treated with respect. Bread is never put on the ground, never cut with a knife. Should a fragment fall when a small child eats, an older child or adult swiftly retrieves the fragment so that none may be lost. Even a fragment of bread is bread. Rez-e-non om non ast.

This feeding reminds us of mannah, the bread from heaven with which God fed the Israelites in the wilderness. The twelve baskets symbolise the twelve tribes of Israel. Yet John locates this feeding in non-Jewish territory on “the other side” of the sea (6:1), inviting those of us who identify as people of God to a broader, more inclusive vision. This story speaks about more than God’s provision for us. It anticipates provision for all, enough for all, fullness of life for all.

****

COVID19. A brief period in which cooperation displaced competition and the leaders of our states and nation put people before profits. At first, some dared speak of a season of levelling, of equalizing, of life and dignity for the poor. Others imagined that our sudden, dramatic reduction in consumption, particularly of air and car travel, might be first steps towards a more ecologically responsible way of life. Sadly, the equalizing aspects of our pandemic response did not last long. Those with insecure work were excluded from benefits. One in four single-parent families ran out of food and money during Victoria’s first lockdown. Hierarchy even crept into public gardens as hospitality businesses ‘pivoted’ to provide sumptuous platters and lavish picnic settings—picnics for a price. People poured onto planes the moment state borders opened.

In Palestine, two thousand years earlier, a boy (or a child or a slave) shared five barley loaves and two small fish. By the grace of God, this gift fed a multitude: everyone ate as much as they wanted, until they were satisfied. No money changed hands. No profits were made. No taxes extracted. No business conducted. No monopolies forged. God’s abundant provision beyond the grasp of Herod and beyond the reach of Rome: a great deal of grass, five barley loaves and two small fish, willingly shared and miraculously multiplied.

This Gospel story reassures us. It addresses our deepest anxieties: that there will not be enough; that we will not have enough: that we will not be enough.

It also challenges and confronts us. The unique details John weaves through the story are significant: the Sea of Tiberias; Passover; five barley loaves and two small fish; a great deal of grass; the dialogue between Jesus, Philip and Andrew. Taken together, these details point to the fundamental conflict between the way of Jesus and the assumptions, habits and aspirations of Rome and more recent empires.

The questions voiced within the story deserve a fresh hearing: the question with which Jesus tested Philip (6:5); Andrew’s question about how far finite resources could stretch (6:9). Two thousand years later, these questions press in upon us. How are we to market food so that the world’s billions can eat? What are our resources among so many?

How will we respond to these questions?

Will we focus on scarcity, on lack, and instinctively assume transactional market responses? I hope not. Jesus’ description of the consequences of Herodian and Roman economics applies equally to contemporary global economic arrangements: “To those who have, more will be given. From those who have not, even the little they have will be taken away” (Luke 19:26). As markets channel more and more of the world’s resources to provide products and services for those who can pay, vulnerable communities are dispossessed, environments degraded, conflicts exacerbated, and inequalities entrenched. Pope Francis calls it “an economy that kills.”

Will we hold back, defeated by the arithmetic: What is so little among so many? Will we hold on to what we have, trying to secure our own needs before we begin to share? I hope not. We experience grace, not when we cling to power and strive to secure our own futures, but when we relinquish control, let go, and trust God. This story calls us to resist the lie that what we have to offer—time, skills or friendship—is so small and insignificant that it’s not worth sharing. It was not immediately obvious how five barley loaves and two small fish would feed the crowd, yet all ate as much as they wanted, until they were satisfied. Put what we have in God’s hands, and it will be enough. Put who we are in God’s hands, and we will be enough.

Will we identify resources already present among us and offer to share whatever we have? Will we embrace the economic vision of Exodus? I hope and pray so. ‘As it is written, “The one who gathered much did not have too much, and the one who gathered little did not have too little.”’ (2 Cor 8:15; Ex 16:18). Five barley loaves, two fish and a great deal of grass. Manna and quails in the wilderness. God’s provision: liberation for all, dignity for all, enough for all, abundant life for all.

Dr. Deborah Storie is a Baptist pastor, lectures in Biblical Studies at Stirling College, and is an Honorary Associate Researcher at Whitley College and the University of Divinity. She lives and works on Wurundjeri land, walks in wilderness places when she can, and enjoys a long association with Manna Gum.