Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, bottom center panel, by Jan van Eyck, Ghent Altarpiece, completed 1432.

Part 3: The Lamb and the Witness of the Cross

In the previous two instalments of this series, I have argued that the Book of Revelation, far from being a book focused on a future ‘end-time’, is concerned with the historical condition of oppression faced by some Christians sometime toward the end of the first century. The book uses strange symbols to reveal to its audience God’s perspective their current situation of suffering.

I have also discussed two of the malevolent characters that appear in the Book of Revelation: the Beast (Revelation 13) and the Great Prostitute (Revelation 17–18). The first, I’ve argued, represents the military might and violence of the Roman Empire, the second its luxury and economic exploitation. It is not difficult to imagine how such characters might function in a book written to communities of early Christians facing oppression and marginalisation at the hands of that very empire, or wrestling with the temptation to conform to its ways.

Revelation’s depiction of these characters forms a critique that is undoubtedly powerful and illuminating. But critique does not on its own constitute faithful discipleship, nor does it unilaterally lead to hope or change. There must also be an embodied alternative, the substance of a different way, or at least a sign pointing in its direction.

With this in mind, what alternative does Revelation provide to the Beast and the Prostitute? What hope do we have in the midst of a world of violence and greed?

Out of empire: The Lamb as a model then and now

Something worth recognising before going further is that, though Revelation is critiquing the Roman Empire, Rome is merely the manifestation of empire that is current at the time of Revelation’s audience. In other words, the social and political reality to which Revelation is responding is not limited to one time period but is an ongoing reality in our world. ‘Beasts’ and ‘Prostitutes’ are not once-off realities, but can be discerned in many places at many points in history.

The challenge for us is to identify such realities and ‘come out’ of them, as Revelation insists (18:4). If we are called to come out of empire, what does this mean exactly? What models does John provide that we might follow?

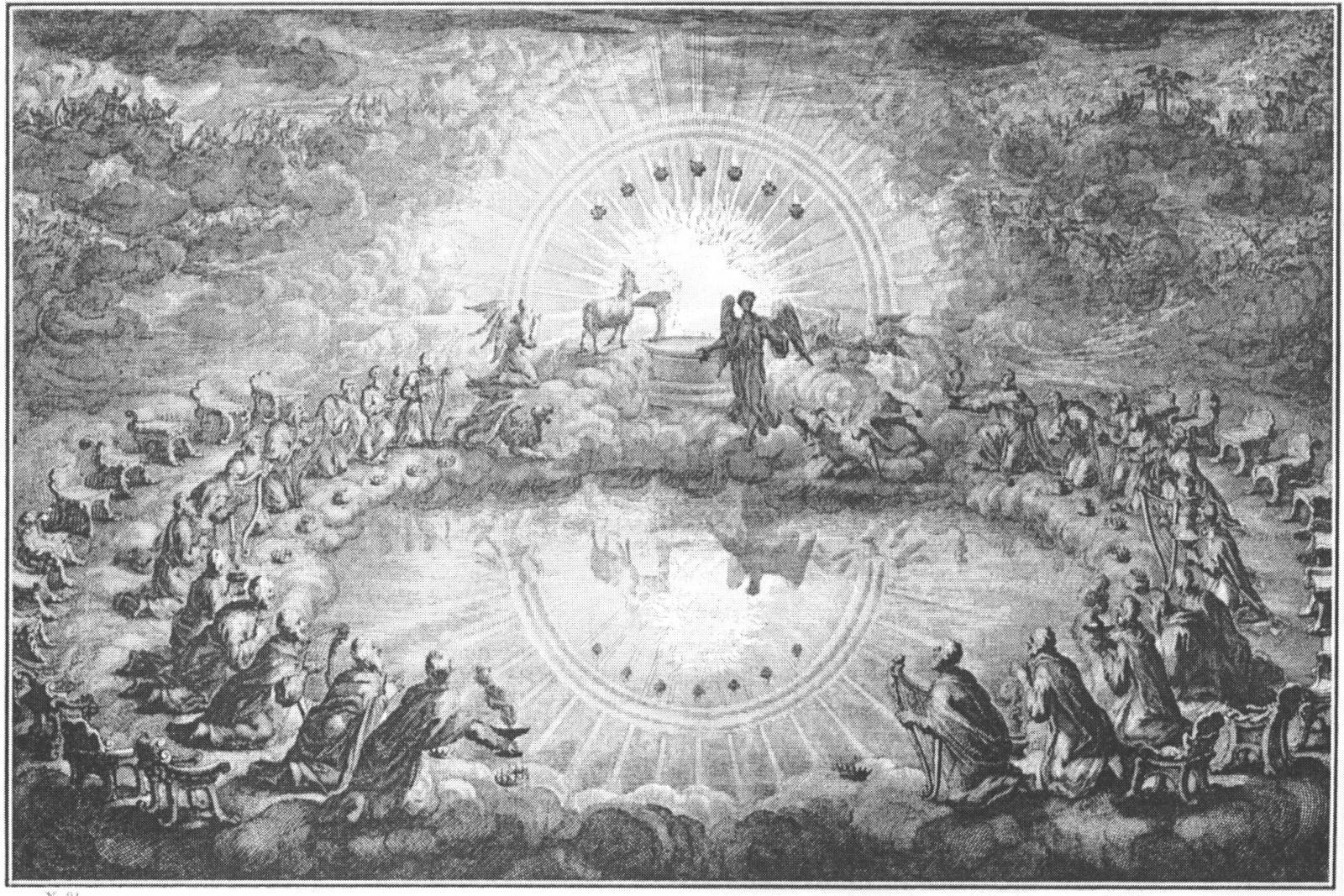

Perhaps the most important image that Revelation offers as an alternative to the powerful and monstrous Beast and the seductive and inebriating Prostitute is the Lamb in Revelation 5.

We are first introduced to the Lamb when John is weeping because no one in heaven or on earth or under the earth was able to open the scroll in God’s hand (5:1–4). One of the elders says to John, ‘Weep no more; behold the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the root of David has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and the seven seals’ (5:5). By this description, which John hears, we are led to expect a lion, as many in Israel had expected—a nationalistic warrior messiah, a militaristic conqueror as envisioned throughout the history of Israel (like David), who will win God’s victory.

This expectation is turned upside-down when what John sees contrasts to what he heard. The conqueror is not a mighty lion at all, but a lamb who has been slain (5:6). The death and resurrection of this Lamb is, as John will learn, how God’s victory is embodied.

This image shakes up the assumption that God will be victorious through lion-like violence and power. It is the Lamb’s sacrificial death that has ransomed the people from all nations (5:9)—the militaristic and nationalistic overtones are muted. Strangely enough, sacrificial death for others is the means by which God will conquer the world. This is a theme that will run throughout Revelation.

There are no doubt countless implications we could draw from the image of the Lamb. There are a few that I’d like to explore.

1. The Lamb tells us about what God is like

The portrayal of the Lamb is central to how Revelation portrays Christ. Indeed, given that the book equates Jesus with God (Rev 1:17–18, ‘the first and the last’, cf. 1:8), the portrayal of the Lamb can be said to be central to how Revelation portrays God. I don’t think it’s an understatement to suggest that the image of the Lamb is of great theological importance. If we want to know what God is like, we look at Jesus, the slain Lamb. God’s nature, according to Revelation, is like the crucified Christ.

(This raises the obvious question regarding portrayals of divine violence in Revelation. While there is no space here to engage deeply with these apocalyptic-style images, what can be said is that we must view these portrayals of divine violence through the lens of the slain Lamb, the paradigmatic image of Christ in the book. They should also be viewed in light of the apocalyptic genre of the book which, as I outlined in the first instalment of this series, depicts things symbolically rather than literally.)

%2C-mosaic%2C-detail-of--central-ceiling-medallion..jpg) |

|

|

Detail of the Agnus Dei, central chancel ceiling medallion of the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, mid sixth century. |

Given Christ is equated with God, it is unsurprising that worship forms a central theme in Revelation, particularly chapter 5. There, those in heaven fall before the Lamb in worship, as they do before God, and proclaim his glory.

There are many things we could say about worship, but two are striking in the context of Revelation. First, worship is mimetic. By this I mean that we invariably conform to the image of that which we worship (as the saying goes, ‘you become like what you worship’). Revelation never says this explicitly, but it is assumed on every page. Idolatry is a problem, and indeed is forbidden, because the worship of idols leads to the distortion of the person in the image of the idol. To worship the Beast is to become like the Beast. To worship the Lamb, however, is to become like the Lamb, which is to become like God.

If worship is mimetic, our understanding of the nature of God and Christ is extremely important since distorted notions of God will lead to distorted worshippers. Revelation—in a way that would be shocking to us if not for the dulling effect of our familiarity—depicts worship first and foremost as glory and honour being directed toward a slaughtered Lamb who is the image of the divine. Moreover, it expects us to conform to this image as those who worship the Lamb.

Second, such worship is subversive. Consider the content of the doxologies (short hymns of praise) in Revelation: they glorify God, yes, but they also challenge all other claims to sovereignty. For example:

’Worthy are you Lord God, to receive glory and honour and power, for you created all things, and by your will they existed and were created.’ (4:11)

’Worthy are you [the Lamb] to take the scroll and to open its seals, for you were slain, and by your blood you ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation, and you have made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on the earth.’ (5:9–10)

These are not merely pious statements; they are deeply political, challenging the claims to sovereignty and power of Rome and its emperor. The caesars, after all, claimed descent from the creators of Rome, saviourhood of the world, and lordship over all. They also demanded the loyalty (pistis; ‘faith’) of every tribe and nation under their dominion.

The worship of the saints in Revelation, however, subverts all such claims. It names the Lamb as the one by whose will all things were created, as the one who saves the world, and as the Lord of a kingdom that shall reign over the whole world. In urging the worship of this figure, and thus conformity to its image, Revelation is pointing to a completely new way of being human, shaped not by Roman power but by divine sacrifice.

The Glory of the Lamb, by David van der Plaats

2. The Lamb is the model for all disciples (or, ‘Witness Wins’)

One of Rome’s key myths was Victoria. Victoria was the goddess of (you guessed it) victory. She was particularly revered by the Roman military, for obvious reasons. It was thought that the Empire was founded on victory and that this was how order and prosperity were maintained. Victoria, then, was intimately related to the myth of Pax Romana (the so-called ‘Roman peace,’ discussed in Part 1), a peace that was established on military conquest.

The early Christians, in contrast, worshipped a crucified person. They had a counter-myth about what entailed true victory. What, for them, constituted such victory?

In Revelation 1:5, Jesus Christ is called ‘the faithful witness’ (also 1:2, 9; 3:14). Likewise, the most important title given to his followers in Revelation is ‘witnesses’ (martys; ‘martyr’). These followers hold ‘the witness (testimony) of Jesus’ (1:2, 9; 12:11, 17; 19:10; 20:4). This does not only mean that they witness about Jesus, but also that they bear the same testimony that Jesus himself bore, namely a witness to God and God’s kingdom over-against all other claimants to sovereignty and victory.

The image of faithful witnesses is most powerful in Revelation 11. The two witnesses here are implied to be Elijah (‘They have the power to shut the sky, that no rain may fall during the days of their prophesying’; v.6) and Moses (‘they have power over the waters to turn them into blood and to strike the earth with every kind of plague, as often as they desire’; v.6). These two were the paradigmatic prophets and witnesses of the Old Testament. Further, in the Old Testament two witnesses were required for a truthful (faithful) testimony in a legal setting. It is no coincidence, then, that Revelation depicts two witnesses; indeed, witnesses as reputable as Elijah and Moses.

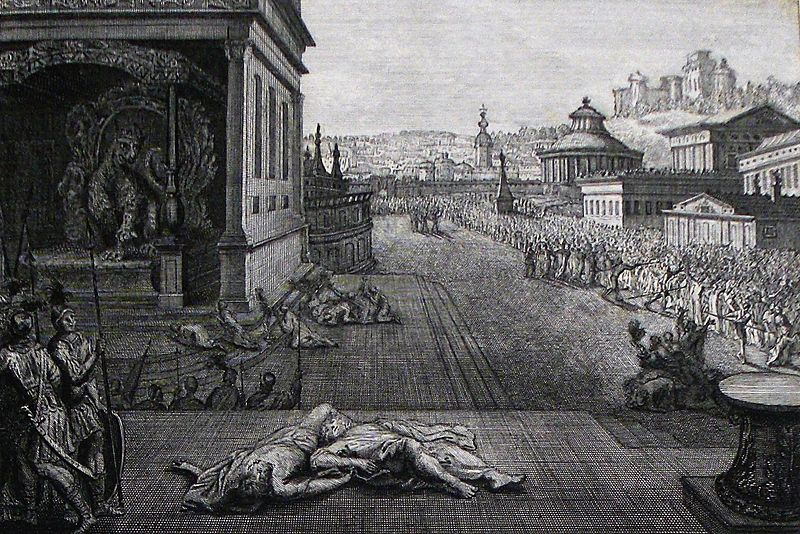

The two witnesses give their testimony and are then killed by the Beast, who comes to make war on them (11:7). The empire’s actions, in other words, reflects its commitment to Victoria—peace and order by military conquest.

The bodies of the two witnesses lie in the street of the great city (11:8). They are not given a proper burial, that is, they are shamed and humiliated (as in near-Eastern culture; 11:9). The people of the earth rejoice over their deaths because the witnesses ‘had been a torment’ to them (11:10). Their testimony, by revealing the truth about the way things really are (as all good testimony does), besieged the people of the earth.

Though the witnesses are killed, they are subsequently resurrected to life (11:11). Their enemies watch as they are raised and as judgement comes on the earth. The people of the earth are said to give glory to God in response, that is, they believe the testimony of the witnesses and become faithful to God and his kingdom, though not without there first occurring the consequences of their earlier actions (11:13).

This, according to Revelation, is the way in which true victory is won: not by military dominance, but by faithful witness to Jesus and his kingdom. It is utterly nonsensical from an earthly perspective, but from the perspective of heaven this is the way of things.

Of course, throughout the history of the interpretation of Revelation 11, the witnesses have been understood not as literal people but as symbolic of the church. The church’s primary job is, according to Revelation, to be witnesses of Jesus in the world, even under the shadow of violence and death. In word and deed, the church is meant to point toward and embody a different reality from that which exists around it, a reality that makes little sense unless the Lamb has truly conquered death through his own faithful testimony.

3. The Lamb’s fate unveils reality

This faithful testimony of the Lamb is most clearly shown in the crucifixion. The violent fate of the Lamb, slaughtered by the violence of the empire, reveals the true nature of that empire. Empire is violent, attempting to erase all who would witness to an alternative story. For it, victory comes through destroying the enemy.

The victory of God, on the other hand, is somehow won in death and suffering. Perhaps this is partly because suffering at the hands of empire without offering a violent response serves to reflect the true violent nature of empire and all oppressive power. This is why disciplined nonviolent actions in our world, including martyrdom, can be and have been so effective in changing public opinion in the long term—they reveal the true and terrible nature of oppressive regimes and open the way for alternative stories and possibilities.

The church’s role has never been to emulate the violent power of the Beast, but rather to imitate the sacrificial witness of the Lamb. To be clear, this does not mean embracing passivism or political neutrality—Jesus certainly did not do so, as evidenced by his at-times scathing political critique and execution as an enemy of the state. Likewise, the two witnesses of Revelation 11 are anything but political sectarians hiding from the world; no, they were public in their witness and became targets of imperial forces as a result.

The example set for us by the Lamb and the witnesses is of rejecting the normal use of power in our world. For them, there is a different, sacrificial way of using power. But more than that, they witness to a different story, one in which love and truth overcome sheer strength and brutality. Only when we lay down our nationalism and culture wars and realpolitiking will we be able to participate in this kind of victory, the victory of God.

Two Witnesses to be Unbound, Mortier's Bible (1700), Phillip Medhurst Collection.

The end of the story

It is worth concluding this series by outlining what Revelation teaches about where the world is headed. Many people use Revelation as a road map for the future, believing that it gives a detailed account of what is to come in ‘the last days’.

It is important to stress that this is not what Revelation is doing. As I said in the first instalment of this series, Revelation is not about the end of the world. Rather, it paints a picture of what was the case in its own historical period, even while it continues to speak to us about imperial realities in our (and every) time and the ongoing need for faithful witness.

Still, Revelation does offer a vision of the end of empire, of a world in which ‘the empire of this world has become the empire of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he shall reign forever and ever’ (11:15).

The vision of the end in Revelation is not of a world destroyed, but of a world that has finally been freed of Rome and all other empires and that has been restored and transfigured into a new, glorious reality.

Indeed, Revelation 21 depicts a vision of a renewed heaven and earth in which the earth is joined together with heaven—the fullness of creation is finally united. This is what it looks like when things have been set right.

The point of Revelation, though, is not to encourage us to passively await this eventual transformation of creation, but to encourage us to live in light of this future reality now, as faithful witnesses testifying about it and as lampstands signalling in its direction. In the present, we are given the opportunity to enact the upside-down reality of God’s victory, to embody the transformed creation in our lives here and now. Revelation, then, asks us to choose between:

- Worshiping the Beast or the Lamb

- Entering the luxury of the Prostitute, or being the Bride of Christ

- Living in the city of Babylon with its oppression and exploitation of the poor and marginalised (Revelation 17–18), or living in the city of the New Jerusalem in which the river of life flows for all people (Revelation 21–22)

- Embodying and enjoying the violence of the Dragon and the Beast, or being willing to nonviolently lay down our lives as witnesses of Christ

Or, to return to the question that has appeared throughout this series, a question that demands our loyalty and imagination: how can the church be the church in the face of a powerful and seductive empire?

Dr. Matthew Anslow is Educator for Lay Ministry in the Uniting Church Synod of NSW/ACT. He’s married to Ashlee and, together with their three young children, they live at Milk and Honey Farm, two hours west of Sydney.

%2C-completed-1432.jpg)