Tax avoidance and tax evasion by multinational corporations continue to play a significant role in depriving people in developing countries of vital revenue to pay for hospitals, health care clinics, schools, universities, aged care mental health services and other community needs. The Australian Government has made commendable efforts to stem the losses Australia has suffered from tax avoidance by multinational corporations and these efforts have made an impact. However, the struggle is far from over and those businesses that advise companies on how to avoid paying tax have been very aggressive in opposing reform measures. Some of those lobbying efforts have been successful at killing off announced reforms.

The support Australia has given to global reforms to address the impact on people in developing countries has been far more limited.

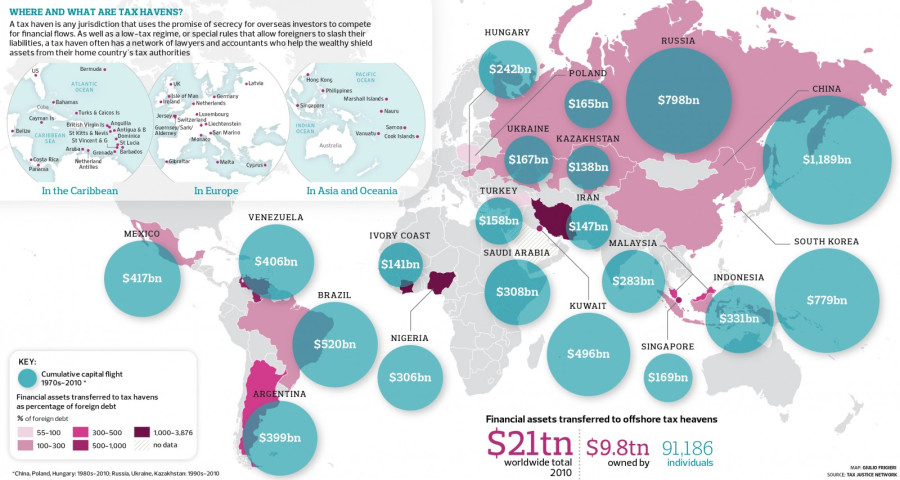

The scale of the problem

The extent of tax avoidance and tax evasion by multinational corporations and other businesses at a global level remains significant. In March 2020, non-government organisation Global Financial Integrity released its assessment of losses to 135 developing countries and 36 advanced economies from 2008 to 2017 from just one type of tax evasion, trade misinvoicing. Trade misinvoicing involves importer and exporter corporations deliberately falsifying stated prices on invoices for goods they are trading. Its aims are tax evasion, evasion of customs duties, money laundering of the proceeds of crime, to circumvent currency controls and to hide profits offshore. The value of fraudulent invoices was estimated to be $13.7 trillion for those 135 developing countries and 36 advanced economies from 2008-17 and the value of trade misinvoicing in 2017 alone was $1,280 billion. Gambia suffered the most significant loss to the value of 47% of its trade in the years 2008-17.

[space]

Global actions

On the positive side, there continue to be discussions at the global level for reforms that could ultimately benefit developing countries. One such proposal is for multinational corporations to have to pay a minimum rate of tax globally. If they have structured their affairs globally to avoid that minimum rate of tax, then governments in places the corporations are doing business would be entitled to collect extra tax up to that global minimum. This proposal would help put a lot of secrecy jurisdictions selling low tax rates out of business.

Tax authorities in 95 countries are now automatically sharing information about assets held by foreign nationals in their jurisdictions. This exchange of information makes it harder for wealthy individuals to hide assets offshore and has seen around $170 billion in extra revenue raised for governments from those engaged in tax avoidance and tax evasion.

The OECD has reported that, since 2015, around 290 harmful tax arrangements being offered by governments to multinational corporations to assist them to cheat other governments of tax revenue have been identified. These have all been amended or abolished.

As of the end of 2019, almost 1,000 financial crime investigators from 100 countries have been trained in several sites of the OECD’s International Academy for Tax and Financial Crime Investigations.

The UN Development Program and the OECD have also set up Tax Inspectors Without Borders to provide on-the-job assistance to developing countries’ tax authorities to tackle multinational corporate tax avoidance and tax evasion. So far, Tax Inspectors Without Borders has allowed developing countries to recover over $830 million in tax revenue.

Australia’s actions so far

In December 2014, then Treasurer Joe Hockey said the Australian Government was being short-changed by the cross-border profit-shifting activities of multinational corporations to the tune of $1 billion to $3 billion a year. Independent research put Australian losses from cross-border tax avoidance in 2013 at $9 billion.

|

|

|

|

Even before that time, notable in Australia’s efforts to address tax avoidance was the establishment of Project Wickenby in 2006. This was a multi-agency task force aimed at preventing people from promoting and using overseas secrecy jurisdictions for tax avoidance and tax evasion. Project Wickenby ended on 30 June 2015 having raised $2.3 billion in tax liabilities, of which $986 million was recovered. Its work saw 77 people charged and 46 convicted and it has emerged as a model for other countries to follow in curbing tax evasion and tax avoidance. Project Wickenby was replaced in 2015 by the Serious Financial Crime Taskforce, which, by June 2019, had recovered $306 million.

Legislation has been passed that requires multinational corporations with more than $1 billion in revenues globally to provide their financial details on a country-by-country basis to the Australian Taxation Office. None of this information is made publicly available, which is a significant shortcoming given that civil society plays an integral part in scrutinising corporate tax behaviour. However, information in these reports is exchanged with the tax authorities of other participating governments. The Commonwealth Government has attempted to ensure compliance with these country-by-country reporting requirements by introducing penalties of up to $450,000 for failing to file the report within 16 weeks of it being due.

The Government has also implemented the OECD Common Reporting Standard for the automatic exchange of financial account information, with the first exchange in 2018. This allows tax authorities in participating countries to know how much money each of their citizens has shifted elsewhere. De-identified data has been made available to developing countries so that they can see the size of assets being held by their nationals in Australia.

In June 2013, the Australian Parliament passed legislation to allow the tax payable by companies with revenues greater than $100 million to be published by the Australian Taxation Office, a small step towards greater tax transparency. However, for 700 privately-owned companies, where the company is at least 50% Australian-owned, the disclosure threshold is $200 million.

The Australian Parliament’s Multilateral Anti-Avoidance Law, which came into effect on 11 December 2015, allows the ATO to tax profits made from Australian residents by multinational enterprises even if the company has not set up a permanent presence in Australia for tax purposes. This is particularly important in the area of digital services, but the law only applies to companies with global revenues of more than $1 billion.

The Australian Government has also introduced a Diverted Profits Tax that came into effect on 1 July 2017. This imposes a 40% corporate income tax rate on multinational corporations with over $1 billion in revenues that attempts to avoid paying tax on profits made in Australia.

Furthermore, the Parliament passed legislation on 19 February 2019 to provide protection and compensation for whistleblowers in the private sector who expose tax evasion and tax avoidance.

The Government has also consulted on requiring tax advisers to have to report to the Australian Taxation Office if they are marketing aggressive tax schemes. This legislation would have given the ATO early warning about tax avoidance schemes and allowed the Government to act to close down such schemes before they became widespread. However, after heavy lobbying by those who provide tax advice to corporations, there have been no public signs of progress that such a measure will be implemented.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board has put in place new rules to eliminate Australia’s unique loophole that has allowed corporations to self-assess the level of financial disclosure they need to provide. Corporations could then choose to use a reporting category of Special Purpose Financial Statements to avoid providing meaningful public financial disclosure.

The ATO believes these reforms have had a significant impact on the level of tax avoidance by large corporations in Australia. In its most recent analysis, released in late 2019, it estimates the gap between what corporations with revenues over $250 million should have paid in tax versus what they did pay was $2 billion, or 4% of corporate income tax for this class of corporation. The ATO believes the gap is primarily driven by differences in the interpretation of complex areas of tax law.

However, in this game of cat and mouse, legions of tax advisers are always on the lookout for the next tax loophole to sell to corporate clients. Thus, the struggle to ensure multinational corporations pay the taxes they should in Australia will remain. However, for those campaigning for tax justice, the main focus remains on enabling developing countries to be able to collect the tax revenue set by their laws and benefit from the resources that are being extracted and exploited by multinational corporations.

For more information, visit the Tax Justice Network Australia website at http://www.taxjustice.org.au/ and the global Tax Justice Network website at https://www.taxjustice.net/.

Dr Mark Zirnsak is the secretariat for the Tax Justice Network Australia and is the Senior Social Justice Advocate at the Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria and Tasmania.