A Christian Ethic of Property (Part 5)

“That’s mine!” protests a child as another child snatches a toy. We’ve all seen it, we’ve all done it. There will be violence soon, unless a parent steps in. Often the parent will mediate the dispute by explaining and enforcing property rights: “You can’t take that toy because it belongs to her.” The idea of property is introduced to limit conflict, but almost immediately it takes root, transmuting into possessiveness. Soon the statement, “That’s mine!” will be used to prevent the other child from playing with a toy not in use.

The aggressive defence of “Mine!” lies at the heart of Australian politics. It underlies a property-owning class who will eject any government that presides over a fall in house prices; it drives the catastrophic clearing of native vegetation by landholders in defiance of proposed environmental regulation; and it emboldens the defence of shameless profits by banks, supermarkets, and gas companies amid rising cost of living pressure and social distress.

Unless we can find a more positive conception of the role of property in society, we will not be able to loosen the many knotty problems we confront: climate change, housing crisis, justice for First Nations. But do Christians hold attitudes to property that are different from anyone else? On the whole, I suspect not.

This is the last in a series of articles that seeks to rewaken a biblical vision of property, and a distinctive practice of property amongst Christian communities. In my view, such an ethic will be both evangelical—a visible witness to Christ—and political—it will shape what policies we vote for and speak out for.

A foundational vision of property

We need a starting point.

Reflecting on the biblical vision of property and the heritage of Christian thought that has been discussed in the previous four articles, the moral theologian, Oliver O’Donovan, summarises the purpose of property as a means by which humans administer common possession of the goods of creation. That is, the act of possessing something represents only a moment when that which is properly ‘ours’ (belonging to all creatures) becomes, for a period, ‘mine’, but not for the purposes of selfish aggrandisement. Rather, through the alchemy of ‘good work’ (see MM Nov 2022), property is a means to contribute to the common good, such that what is ‘mine’ is meaningfully transformed into something that once again becomes ‘ours’. Property releases good work in the world that serves the community of creation.

When property becomes a means of hoarding wealth, of exerting power over others, or of pursuing a selfish independence from others, then property becomes improper. Currently Australia is founded on ‘improperty’: how do we transform it?

In what follows I will attempt to outline a proposal for a positive, practical, moral, and political ethic of property which attempts to forward a Christian vision within the realities of twenty-first century Australia, taking account of justice for First Nations, the housing crisis, economic inequality, and more. ‘Property’ here, does not just refer to real estate (although land plays a central role), but to all that we possess: land, houses, cars, and all our stuff.

I emphasise that this is a proposal: it is a tentative sketch which represents an attempt to recover something that has been largely lost to Australian Christians. It should be read as first word, not a last word.

Property is a means to contribute to the common good, such that what is ‘mine’ is meaningfully transformed into something that once again becomes ‘ours’.

Living on stolen land

Two hundred and thirty years down the track of settler colonisation, we have to frankly admit that it cannot now be undone. The legal-economic tapestry of property rights that supports 28 million people cannot now simply be erased.

I know of some Christians, who are rightly grieved by the deep wrongs underpinning the foundation of Australia, and who have come to the conclusion that it cannot then, be ethical for a non-Indigenous Christian to own land. But this is pointless and self-defeating. It requires putting one’s life at the disposal of landlords, who do own the property, and are far less likely to think about how this bit of property might contribute to the broader social good, as opposed to merely personal accumulation. It would resign property rights over to those in the community with the most negative conception of property.

However, acknowledging the reality of our departure point in 2025 need not amount to a resignation to (much less, a justification of) the deep injustices that still afflicts the First Nations of this continent. It is incumbent on Christ’s people to seek whatever healing and justice can now be sought. There is still a great deal that can, and should, be done.

Home ownership

Currently, the primary possibilities for housing in Australia are to be an owner or a renter. As has been stated, there is virtually no place in Australia in which freehold property is not stolen land; however, for most people, the idea of divesting one’s family home to traditional owners is simply out of the question. This means that, whether or not we own or rent, all non-Indigenous Australians are, in a sense, in debt to First Nations people. The biblical injunction with regards to land ownership is that we are ‘but aliens and tenants’ on the land (Lev 25:24): people with a responsibility of stewardship. How much more so, then, is such a responsibility forwarded by an outstanding debt to First Nations?

Residence on stolen land therefore obligates us to work for Indigenous justice whenever and however we able. This is first and foremost a political obligation. It requires endeavouring to listen to, and understand First Nations voices, and to join with them in their struggle for ‘Truth, Treaty, and Voice’ and the ongoing quest for land rights in the form of title and/or custodianship. Tragically, we missed one such an opportunity in 2023, but the debt remains. In Victoria, another opportunity will be presented in June this year when the Yoorook Commission presents a final blueprint document for the redress of injustices in the area of land and water, education, and health and housing. However, the political quest for Indigenous justice is not restricted to the arenas of federal or state governments: it can be pursued at a very local level. This requires becoming acquainted with the local traditional owners, learning about their context and supporting their goals and objectives.

Whether or not we own or rent, all non-Indigenous Australians are, in a sense, in debt to First Nations people.

Larger landowners

In the case of large landowners—whether wealthy individuals, organisations, or private companies—there are more possibilities, and perhaps responsibilities, for thinking about some level of divestment of property to First Nations groups, or entering into joint custodianship arrangements. There is particular scope for this in the case of environmental philanthropy, where land is purchased privately to ensure conservation of its ecological values. There are now a number of examples around Australia where such projects have been twinned with Indigenous justice concerns, either divesting ownership wholly to traditional owners, or including them as custodians of the land, restoring opportunities to care for Country (for example the HalfCut initiative in the Daintree, QLD, divesting to Kuku Yalanji traditional owners; and the Cooroong Lakes Project, SA, partnering Cassinia Environmental and Ngarrindjeri traditional owners). There are also cases of farming properties that have entered into agreements with traditional owners to give them access to Country and voice in caring for Country. I hope we can profile some of these stories in Manna Matters in the future.

Church land

I think there is a particularly sharp case for various Christian denominations to be thinking about their responsibilities for some divestment and joint custodianship of property. This is for two reasons: firstly, some denominations (especially the older mainline churches) are large owners of land, both urban and rural, some (much?) of which is severely underutilised. Secondly, the fact that some of this land was in fact granted to churches by the Crown as the first ‘beneficial owner’ following Indigenous dispossession, is an open moral wound undermining the vocation of churches to be bearers of the gospel of reconciliation. Irrespective of such original land grants, if churches take seriously their calling to be the Body of Christ in the world, then they simply cannot ignore the foundational and unaddressed injustice by which churches have come to exist in this continent in the first place. There are number of ways this can begin to be addressed:

Acknowledgement of Country: apparently, since the failed 2023 ‘Voice’ referendum, many churches have retreated from what was a growing practice of including some acknowledgement of Country in their gatherings. This is a shameful instance of churches cowering at a change in the winds of public opinion. No wonder so many Indigenous Australians have shaken the dust of Christianity from their feet, bitter at the shallow ‘fair weather’ reconciliation of the churches. Acknowledgement of Country represents an absolute minimum of truth-telling, and if we cannot even do this, we are nowhere.

Paying the rent: in the absence of broader structural justice for First Nations people, churches can themselves undertake to ‘pay a rent’ to First Nations peoples for the use of land that was rightfully theirs. This is not without complexities: should it be calculated somehow in relation to current commercial rents, or as a proportion of income, like a tithe? Should it be paid to the formal traditional owner bodies, or should some way be found to include the many ‘historic Indigenous Australians’ whose dispossession is such that they cannot claim membership in any such bodies? Should priority be given to Indigenous Christian ministries or more broadly representative Indigenous groups? I do not offer an opinion, and note that there are differences of views amongst Indigenous leaders. But even discussing these questions would be a significant step forward for churches in grappling with the manifold realities of Indigenous dispossession.

Shared space: many churches have underutilised spaces and facilities that could be made freely available to Indigenous groups and/or services, forming an ‘in kind’ form of paying the rent, and potentially opening up the opportunity for new and deeper relationships.

Divestment: those denominations that have large real estate holdings should be examining the possibility of divesting some of this property to First Nations people, especially where they are closing down non-viable congregations. This could take the form of simply giving the property over to First Nations groups; transferring ownership but retaining use through a lease-back arrangement; or directing a percentage of all property sales to Indigenous organisations. This raises many similar questions as above, but such complexities should not be used as an excuse to do nothing. Of course, the major obstacle is the fact that denominations are often using land sales or rental income to bolster their declining financial sustainability, thus making this a very hard proposition to come at. But addressing historic injustice can never be costless. Church fears about financial security played a large role in driving their inadequate responses to revelations of child sexual abuse, and it is arguable that this failure meant churches have ultimately paid a much higher price in lost credibility. We should be wary of such false accounting when addressing our colonial legacy.

I should note that some denominations and local churches have made beginnings in these directions. This is to be commended, but there is still much to be done.

Less stuff with more care

If we think about property as: (i) that which enables a decent standard of living for my family; (ii) a concrete part of creation which I am responsible to steward; and (iii) and a means to release good work into the world; then this suggests a primary task for Australian Christians is to recalibrate our idea of how many possessions we need in order to achieve these things. The Early Church Father, Clement of Alexandria, advised: ‘Just as the foot is the measure of the sandal, so the physical needs of each are the measure of what one should possess.’ Given that Australians have one of the highest ecological footprints on the planet, this suggests that a primary goal for Australian Christians should be to attempt to live with less stuff, and with more care. Very briefly, here is some of what that could mean:

Housing

Aspiring to more modestly-sized housing, and giving more attention (time and money) to energy and water efficiency.

Understanding a house and land not as an isolated packet of possession (‘mine’), but as one part of a much bigger ecology, even in urban areas, and doing what we can to make it more hospitable to the community of creation (especially native animals and soil microbes). (See articles in MM Aug 2023, Oct 2020, June 2010)

Cars, clothes, computers, and other stuff

Can we do with fewer of all these things, can we make them last longer and can we take greater care in obtaining and disposing of them? (There are so many MM articles on this: search ‘ethical consumption’ under ‘All articles by topic’ on the website.)

Given that Australians have one of the highest ecological footprints on the planet, this suggests that a primary goal for Australian Christians should be to attempt to live with less stuff, and with more care.

Housing and economic inequality

The housing crisis in Australia is not just a crisis of the affordability of housing, it is a crisis of a deepening social division between those who own property and those who do not. Once again, a Christian approach to property requires attending to our personal ethics within this sphere and attending to the politics of property in Australia.

Investment properties

Christ’s people must absolutely reject the use of ‘real estate’—i.e. someone’s home—as a means of building wealth. Rather, those Christians who own investment properties should see them as an opportunity to invest in the kingdom of God. This requires a profound rethink of the ethics and responsibilities of being a landlord – someone with power over someone else’s home. What does it mean to be a Christ-centred landlord in the midst of a housing crisis? One place to begin answering this question is within church communities themselves. Can those in the community with investment properties, or other financial assets, assist those in the community who are locked out to secure decent, stable, and affordable housing? For a fuller discussion of this see MM Dec 2014.

Church land

Around the country there are churches with unused or vacant land that could be made available to partner with organisations seeking to deliver affordable housing. There are now numerous examples of this which demonstrate that these partnerships can be mutually beneficial. Hopefully we will profile some of these schemes in coming editions of Manna Matters.

Housing politics

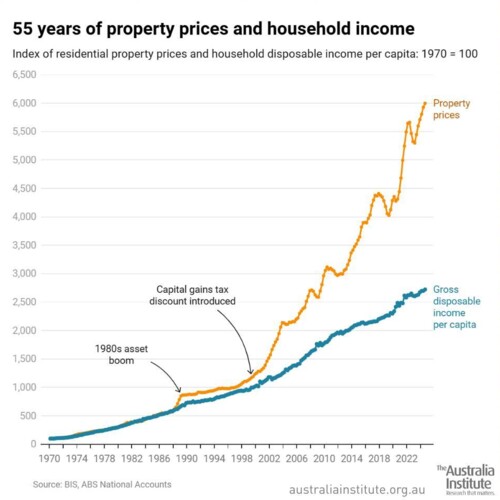

The housing crisis has not just happened, it is an outcome of policy design that has been developing for twenty-five years: a train wreck in slow motion, where no government has yet felt moved to pull on the brake. Addressing the housing crisis requires a multi-pronged approach, including: overhauling taxation at federal and state levels (capital gains discount, negative gearing, stamp duty, land tax); a massive re-investment of governments in providing housing; and encouraging more and better non-ownership access to housing than simply short-term private rental (see MM June 2019, MM Summer 2025). The upshot is ultimately that house prices must come down, and Christian home owners and investors must be prepared to vote against their own short-term financial interest, and for the common good.

This graph from The Australia Institute shows that a major cause of rising house prices has been increased demand from investors. The research shows restricting negative gearing to newly built housing and scrapping the capital gains tax discount would reduce speculation in the housing market and allow more first home buyers to get into their own home.

A new political vision for property

Beyond housing, a vision of a just, neighbourly, and sustainable Australia requires addressing the massive concentrations of property-as-economic-power that have been allowed to congeal in key sectors of the economy, especially banking, mining, supermarkets, agribusiness, pharmaceuticals, and digital technology. The vested interests of big money are playing a decidedly obstructionist role when it comes to doing what we need to do to face the massive challenges of the twenty-first century. This will require some smart regulation from government, and may even require employing some form of anti-trust (monopoly-breaking) legislation.

Moreover, a new political vision of property should include rethinking elements of the privatisation binge of the previous three decades, especially in the areas of energy and transport. Rather than idolising private property, we should be asking what a given sector of the economy needs to do serve the common good, and seek to apply the most appropriate property regime to achieve that, whether that be private, collective, or some form of public ownership. An overarching goal should be to break up distorting concentrations of property (i.e. economic power) and seek to distribute access to, and stakes in, property, as widely as possible.

Currently, such thinking is mere fantasy within Australian politics. To be advanced it will require people with a new and hopeful vision of social life, people who are prepared to say what is not popular. Where will they come from?

Churches re-imagining common property

How do we overcome our possessive individualist attitude to property? We need communities where there is both the opportunity and common desire for thicker relationships of mutual dependence. Believe it or not, the local church is a purpose-made social technology for economic cooperation, however, this aspect of its vocation has been largely mothballed in the Western Christian imagination (see also MannaCast ep. 11). However, it is in this community, more than any other, where people can learn what it means for what is ‘mine’ to become ‘ours’.

Most people think the example of economic community described in Acts 2 and 4 is an unattainable chimera, but actually the steps to begin building economic cooperation are smaller and easier than many people think. The major caveat to this is that they generally require a certain amount of geographical proximity. Sharing place and sharing property go together.

Economic cooperation is not one big, scary thing, but rather a series of practices that can begin very modestly and grow organically (see MM Sept 2019). These include things such as:

- Basic material support (e.g. meals in a time of crisis)

- Sharing of knowledge and know-how (gardening, DIY, preserving, etc.)

- Simple sharing of stuff (tools, cars, etc.)

- Shared labour (working bees, help with projects)

- Cooperative purchasing (bulk goods)

- Co-ownership (a bigger step: buying big lumpy things together that don’t make sense replicating in a community, such as mowers, whipper snippers, trailers, etc.)

- Income sharing (today called ‘crowdfunding’, all churches already do this with their offering, but it is a practice that can be extended in multiple directions)

- Renewing commons (nurturing assets, such as church facilities, as something in which the whole community can have a stake)

These are all things that can be done in small steps, where we learn to relax our possessive muscle and discover the richer life that awaits when what is ‘mine’ becomes ‘ours’ in some meaningful way. This is a subject that warrants much more conversation and, for those who are interested, will be explored in detail in Manna Gum’s ‘Kingdom Communities’ series of webinars in June.

I am convinced that if the church in Australia is to undergo some sort of renewal, it will likely be connected to the recovery of the idea that local Christian communities are economic communities in which there is a rich sharing of everyday material life, underpinned by a transformed heart-disposition to our property. As Acts 2 makes clear, when the Holy Spirit moves, this is one of the first and most natural outcomes.

The local church is a purpose-made social technology for economic cooperation.