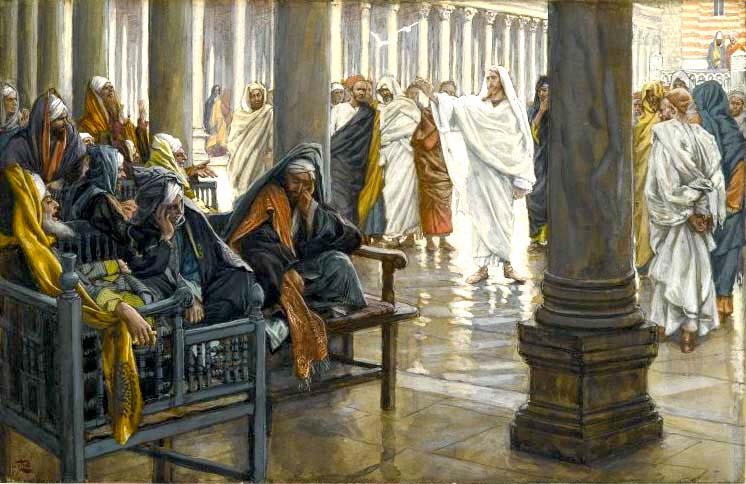

Woe Unto You, Scribes and Pharisees by James Tissot (1886)

Part 3

At some point when I was thinking about how I would write this article, I listened to a song by the Canadian folk band, The Great Big Sea:

I want to be / Consequence free

I want to be / Where nothing needs to matter

I want to be / Consequence free

Just sing / Na na na na na na na na

While I can’t but help love this upbeat song, I realised that it is expressing a profoundly misguided sentiment. The singer is wishing to be able to party hard without suffering any adverse effects of such actions. Of course, he is wishing for such a thing precisely because his life experience tells him it is not possible. It seems a life-affirming sentiment, but in reality, it is a denial of our created existence in an interconnected world where all of our actions have consequences, whether for good or ill. When Jesus offered life in abundance, he did not have escape from this world in mind, but something much better.

In the previous article, I attempted to unpack the ideas that lie behind the Old Testament language of judgement. I argued that although the ancients used the idea of divine punishment to explain judgement, what they were really describing was the operation of cause and effect in the moral universe that God has created. If there is ‘punishment’ in judgement (and I do not think such language is helpful to us), it is the punishment that we bring upon ourselves. What we call ‘judgement’ is that moment of disclosure when what has always been true, but has generally been ignored, suddenly becomes plainly apparent. We are in such a moment now with climate change.

In this article, it remains to see how judgement plays out in the New Testament. I will suggest that the central idea remains fundamentally the same, but with the coming of Jesus there is a surprising new twist. Finally, I will try to hint at how the biblical idea of judgement plays out within human history and in our own time. If judgement is the disclosure of reality, then we should be able to see it happening. It seems laughable to attempt such a thing so briefly, but as Chesterton helpfully advised, ‘if a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.’

Judgement in the New Testament

On a superficial reading, the gospels can seem a bit confusing on the matter of judgement. In various places we are told not to judge, to judge for ourselves, to judge with right judgement, that Jesus does not judge and that Jesus is our judge! Clearly there is a lot to unravel here and to do so well would require paying attention to all the different contexts in which the concept of judgement appears. We do not have space for that here, but let me at least suggest some baseline concepts that will help us understand it better.

First, we need to address the underlying discomfort that we, postmodern individualistic readers, bring to the subject. Jesus speaks about judgement often and much of it is pretty uncomfortable. The language is strong and the imagery dire and it seems to confirm our worst fears about a vindictive and arbitrary God. I suspect this is largely for two reasons:

i) In the back of our mind, we are applying these statements about judgement to our own little world of petty transgressions: we have treated someone badly, we are self-indulgent, we made a mistake of judgement (!) about a particular situation. That is, our consciences are troubled by our own judgement of ourselves.

ii) In spite of a sometimes negative assessment of ourselves, when we feel we are being judged by another (including God), we can’t shake the feeling that it is being judged against an arbitrary standard. It doesn’t feel ‘fair’.

Ultimately, we are worried that our lives will be weighed in the balance by an arbitrary and vindictive God who doesn’t share our sense of compassion, fairness or proportion. Our worry betrays a lack of confidence in who God is and what Jesus is about.

I don’t want to suggest that what I have just called ‘petty transgressions’ are not actually important to the texture of our day-to-day lives (they are very important), but if this is the only canvas we bring to the texts on judgement, we are missing the big picture. What if, instead of our own petty lives, we bring to mind the big stuff that makes up human history: war, slavery, genocide, radical poverty alongside radical wealth, dying oceans, disappearing forests, species extinction? These are not matters of petty existential angst, but matters that cry out for justice! Notice how the following teaching of Jesus takes on quite a different tone when we begin to apply it to the climate emergency:

You hypocrites! You know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky, but why do you not know how to interpret the present time? And why do you not judge for yourselves what is right? Thus, when you go with your accuser before a magistrate, on the way make an effort to settle the case, or you may be dragged before the judge, and the judge hand you over to the officer, and the officer throw you in prison. I tell you, you will never get out until you have paid the very last penny. (Luke 12:56–59)

In the midst of a multi-dimensional ecological crisis, might we not say that that the Earth stands as our accuser and that if we do not come to some acceptable terms with the Earth, we will surely pay a very high cost? Surely this is the very position we find ourselves in and it is the secular scientific establishment who are warning us of impending judgement. The Bible’s language is strong precisely because, as we are finding out with climate change, the stakes of human action and consequence are so very high.

Which brings us to the meaning of the word ‘judgement’. In the New Testament, the Greek word that is translated as ‘judgement’ is krisis, from which we get our word ‘crisis’. The correlate of this word in Hebrew is mishpat, which is most often translated in our Old Testaments as ‘justice’. Whereas we tend to think about judgement as unfairly writing someone off—‘Don’t judge me!’—mishpat and krisis are much more serious concepts: they refer to an intervention by a ruler or court to restore right where wrong has been done. Judgement is the tipping point of crisis, when justice is demanded.

So how do we relate this krisis to Jesus? As I have mentioned, Jesus speaks about judgement a lot. In the synoptics, this mostly relates to the concept of a ‘Day of Judgement’, which I shall come to in a moment; but in the Gospel of John, judgement is discussed repeatedly in relation to the person of Jesus himself. We see this most famously in chapter 3, which, in this case, is most consistently rendered in the New American Standard Version:

For God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world, but that the world should be saved through Him. He who believes in Him is not judged; he who does not believe has been judged already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God. And this is the judgement, that the light is come into the world, and men loved the darkness rather than the light. (John 3:16–19)

A major theme of this gospel, explored in John’s difficult style of holding paradox in tension, is the way in which Jesus refuses to judge and yet brings the moment of judgement with him. At one level, Jesus comes ‘full of grace and truth’, calling all to repent and opening the path to salvation. At another level, the very coming of the light of love into the world presents us irrevocably with a choice and in our choice lies our judgement. As John’s gospel rises to a climax, when it is clear that this embodiment of love will be murdered, Jesus declares: ‘Now is the judgment of this world’ (12:31). When truth and love are rejected, horrible consequences must follow. But notice the final twist: the suffering of humanity’s calamitous choice falls on God’s self. The cross is God suffering the consequences of humanity’s judgement, which is the full disclosure of our predicament: when we were visited by Love, we killed it. As the great mystic, Julian of Norwich, once proclaimed: ‘The worst has already happened and has been repaired’.

The rest of the New Testament bears witness to this dual story of grace and judgement. The way is opened for all to enter salvation, irrespective of past history, but notice how it must be accomplished: by each participating in the crucifixion by which God bears the judgement of the world, and so participating in the healing that follows. ‘For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.’ (Rom 6:5) Judgement is not in tension with the economy of grace but an integral part of it.

But the grace of resurrection life is not that of entering a new creation in which there are no consequences for actions. It is not what Bonhoeffer called ‘cheap grace’, but rather a restoration to the moral ecology of love. ‘Do not be deceived. God is not mocked. You reap whatever you sow.’ Interesting that the Apostle Paul states this in Galatians, a letter all about freedom from the Law. Paul staked his whole apostleship on a revolutionary claim about the profound human freedom being discovered ‘in Christ’: ‘It is for freedom Christ that has set us free’ (Gal 5:1). Yet Paul never imagined that freedom meant that ethics and morality become a kind of playdough in the hands of humans: able to be re-shaped endlessly according to new desires and inclinations. Rather, Paul is emphatic that humans exist within a pre-ordered moral universe. When he talks of the restoration of freedom, he does not mean what we moderns tend to mean by ‘freedom’: the removal of all constraints and obligations upon individual will. Paul’s idea of freedom is almost the opposite: we are being restored to a ‘new creation’, the restoration of a fractured cosmos back into the healing communion of love for which it was intended. That is, we are being restored into connection and relationship.

What of that vital teaching of the Sermon on the Mount, ‘Judge not, that you may not be judged’? It is not really that complicated: Jesus is teaching that we must never presume to weigh the soul of another human being, because the full disclosure of reality is open only to God. Just as God holds the offer of grace open to the utmost, so must we. However, we are never absolved of the responsibility of making moral judgements, however provisional they must be, about the times and circumstances we find ourselves in: ‘Judge for yourselves what is right’ (Lk 12:57); ‘Do not judge by appearances, but judge with right judgement’ (Jn 7:24).

And what of that final ‘Day of Judgement’ – a day of crisis and of justice – that Jesus referred to so often? There is no doubt that he invokes this image as a strong warning: the stakes of our life choices are high; there is a road that brings life and a road that wastes life (which is the meaning of the image of Gehenna). It is perhaps a measure of both the material comfort of our lives and the insecurity of our minds that we find this such an unnerving concept; yet for the Hebrew people, as for so many of the world’s downtrodden and oppressed, the vision of a day when right will be done, creation restored and all that is wrong removed has long provided a vision of hope to hold on to. We fear being weighed by a demanding and arbitrary God, when we should look forward to a day when all our faltering efforts towards love and justice are brought to a completion by the God of love and grace and the world is healed. Of course, such a day is shrouded in mystery and beyond our comprehension: we can only speak of it with our own inadequate words and images. Yet the message is clear: if we are joining ourselves to the life and love of Jesus, then we have nothing to fear from such a day.

Judgement in history

‘Do not be deceived. God is not mocked. You reap whatever you sow.’ This is the moral ecology of an interconnected creation and the truth of it can be seen again and again throughout human history. After the Second World War, historian Herbert Butterfield wrote an important little book that is hardly remembered today, entitled Christianity and History. Butterfield was asking what the study of history, a secular academic discipline, might contribute to religious faith. His first two conclusions were: (i) the study of history confirms what the Bible says about human nature – ‘All men are sinners’; and (ii) the moral judgement of human nature is something that plays out within history. That is, so many of the catastrophes that play out in history are the product of civilisational moral failings. The catastrophe of the First World War was a product of European competitive nationalism in which nations ‘gambled very highly on what was an over-optimistic view of the character of man’. No one thought that what did happen, possibly could happen. The Second World War was, in large part, a product of a ‘peace’ imposed by the victors of the first war, who sought vengeance and denied their own culpability. The Great Depression in between these two events was a product of an over-optimistic view of the competence and propriety of capitalists.

One of the things Butterfield so usefully clarified is that this sort of judgement in history was a judgement upon systems and not upon persons. Stalin, possibly one of the most despicable human beings in history, died while still on top, at a ripe age, and probably of natural causes. But when, a generation later, the judgement came on the system he had erected, it came with a swiftness that shocked the world and which few people had seen coming. With hindsight, historians agree that the flaws of the Soviet system – its callousness, its hypocrisy, its punishment of truth, its outraging of human dignity and freedom (to name but a few) – simply could not be sustained over time.

Where the Old Testament view of causality would have attributed the collapse of the Soviet Union to the intervention of God, we can see that human actions bring such consequences upon themselves. As I argued in the previous article, we do not need to see a stark contradiction between these two: the consequences of history are the product (the ‘judgements’) of the moral cosmos God has created, in which all are things are inter-connected and all actions produce reactions, whether for good or ill.

This draws our attention to another feature of such judgements within history. Because it is systems and not people that are judged, the judgements of history fall, like rain, on both innocent and guilty alike. Very often it is the innocent who suffer the worst from such catastrophes of history and this is yet another reason why the warnings of the Bible about judgement are so strident. When human hubris and blindness run amok at a civilisational scale, there is no limiting the liability. And this ‘judgement’ in itself reveals another deep truth about God’s moral order: we are all in this together.

Judgement now

As I have been arguing throughout these articles, we can see all of this playing out with great clarity in the case of climate change. At the root, it is the result of humans imagining that we exist outside of the created order and can bend it, like plastic, to our own will and imagining that the moral order is simply something that we construct – it is not real. We are learning to our own hurt that neither of these are true and it is the innocent – Pacific islanders, Bangladeshi farmers, Sudanese herdsmen, not to mention the non-human species of the planet – who are suffering first and most. Reflecting upon the fact that human nature remains unchanged, yet human power has increased exponentially, Butterfield mused:

I am not sure that it would not be typical of human history if – assuming that the world was bound some day to cease to be a possible habitation for living creatures – men should by their own contrivance hasten that end and anticipate the operation of nature or of time, because it is so much in the character of Divine judgement in history that men are made to execute it upon themselves.

The Old Testament lament of sackcloth and ashes is an appropriate first response to such threat of judgement. We cannot move forward in hope if we do not own how we got here. But while the grief of lament can never really leave us, we cannot stay in that place. The witness of the Bible is that even in our darkest hour, there is a light from heaven that can break in, if indeed that is what we seek.

But what of the global pandemic we are currently experiencing? Can we see the sorts of lessons we see in climate change playing out here too? This is admittedly a more complicated case than climate change and we need to be more tentative in coming to conclusions. Certainly, we must reject the tendency of some Christians today (and throughout history) to blame such events on the moral failings of the other, usually their current political enemies, and who seem to exhibit a certain gleeful shadenfreude at the spectacle of suffering.

Aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, Meulaboh, Sumatra. We must avoid the temptation of

saying that God wills such things.

Also, we should not imagine that every bad thing that happens is a consequence of human action. The 2004 Indian Oceantsunami was a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions to which we can attribute no human responsibility. Again, we must reject the temptation to say, as some Christians did, mysteriously shrugging their shoulders, ‘If it happened, God must have willed it’. God never wills such things. All that such events tell us is that it is not only humanity that is broken, but creation herself: they are another sign that things are not as God wills them. Bad things happen and humans touched by God’s love seek to heal them. (That said, there was a great deal to be learnt from the human response to the disaster, where we witnessed what Naomi Klein called ‘disaster capitalism’.)

Pandemics are caused by a complicated mix of ‘natural’ occurrence and human action. Most pandemics in history have involved animal diseases crossing over into the human population. This sort of disease crossover is just something that can happen in nature, but it happens more often when humans confine animals in unhealthy ways, or when we impinge too much on animal habitat. Both are now happening on a scale never before known. But disease crossover does not equal pandemic; the experience of pandemic is, almost by definition, the product of advanced human civilisation in which there is transcontinental mobility and exchange. The very complexity and high level of exchange and interconnection of our present globalised economy makes us more vulnerable to pandemic than ever before.

But is there a moral judgement to be drawn from this? Once again, we need to be more tentative. To conclude that exchange and movement of peoples between the different regions of the world is a bad thing would seem to be the wrong conclusion to draw. But perhaps we could say with more confidence that the forms and extent of present-day global exchange are problematic and there are other reasons that confirm this: the impact of transport emissions on climate change, the erosion of local production and the proliferation of ‘modern slavery’ are just a few more examples. We can also say with some confidence that our continued impingement on habitat and unnatural confining of animals will increase the frequency of disease crossover and thus the likelihood of pandemic. Perhaps the other significant area where the experience of the pandemic has shed a moral light is on the health of our political and economic systems, but this is a complex subject and we cannot open it up here. When we are finally able to look back on this experience, there will be many judgements that have to be made about our response if we are to learn our lessons and avoid such a catastrophic event again. As Herbert Butterfield observed, hindsight is itself a gift of human judgement.

A final word

I have been arguing throughout this series that being able to see, and come to terms with, what the Bible means by ‘judgement’ is a necessary part of being able to see, and being able to communicate, what good news looks like for us here and now. At the heart of being able to comprehend judgement is being able to comprehend the moral ecology of the created order: all things are connected and all actions have consequences. We reap what we sow: ‘If you sow to your own flesh, you will reap corruption from the flesh; but if you sow to the Spirit, you will reap eternal life from the Spirit. So let us not grow weary in doing what is right, for we will reap at harvest time, if we do not give up. So then, whenever we have an opportunity, let us work for the good of all’ (Gal 6:8).

'Because it is systems and not people that are judged, the judgements of history fall, like rain,

on both innocent and guilty alike.'

In closing this series on judgement, it is appropriate that I say something of what it means for the Christian church. ‘For the time has come for judgement to begin with the household of God’, the Apostle Peter advises his flock (1 Pet 4:17). Christians have often made the mistake of assuming that judgement is something the church gets to say about the world; but as the old saying goes, whoever points the finger has three fingers pointing back at them.

From what I have been saying it should be clear that the church is not immune to the moral ecology of action and consequence. We live in a period when, across the Western world, but especially in countries like Australia, there is a markedly negative attitude to the religion that shaped our culture. We miss the point if we complain that Christianity is the victim of misrepresentation and one-sided stereotyping. In the longer arc of history, this ill-feeling towards Christianity should be understood as the inevitable letting loose of centuries of stored-up resentment at the hypocrisy of a church wedded to its social prestige and often involved in oppressive and abusive power, all the while proclaiming itself as representing the gospel of Jesus. In many ways, I think it is true to say that the church is under judgement.

If we are to be people who hope to be bearers of the good news of Jesus in the world, then we need to come to terms with this judgement on the church. It demands a proper moment of lament, of sackcloth and ashes, and perhaps, in the interim at least, it demands a penance of silence. Perhaps the words of the church cannot be heard constructively again in the wider world until the church first learns to shut up for a season. But the ultimate response judgement calls forth is repentance: a new clarity of sight about where we went wrong and the ability to take a turning at the crossroads, to choose the road less travelled. Judgement is the moment of crisis, the opportunity to discover the ‘life that really is life’ (1 Tim 6:19).