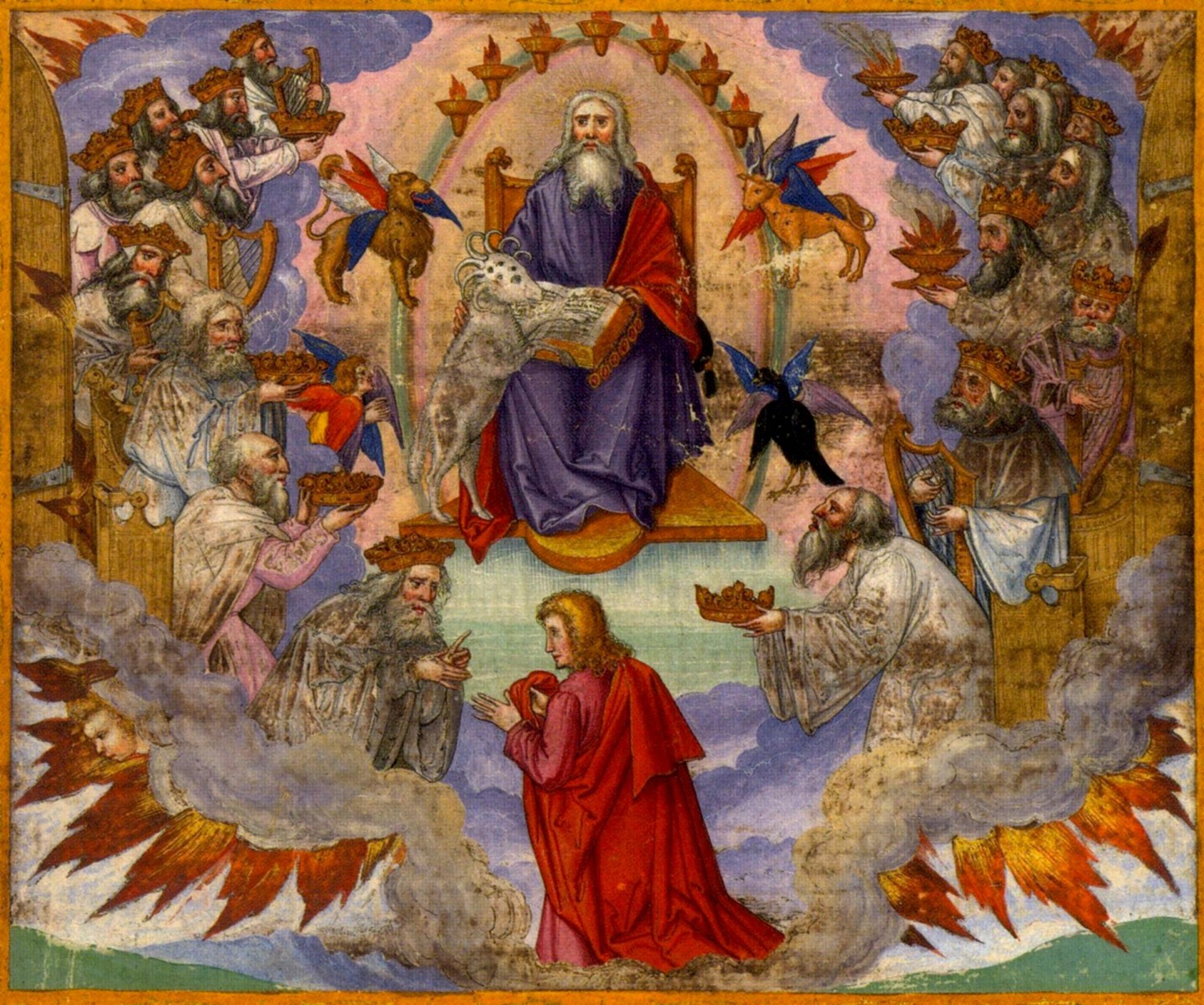

John's vision of heaven, by Matthias Gerung (1530)

Part 1: The Beast

I think it is safe to say that the Book of Revelation is a divisive text. The reasons for this are no doubt numerous, though the book’s complex and intriguing character probably plays a large part. Such characteristics are probably also to blame for two of the main attitudes to the book I have experienced, namely, avoidance and obsession.

Over the next few articles focused on this enigmatic text, my aim is twofold. First, I hope to provide a helpful model for navigating the Book of Revelation. This doesn’t mean I will address every burning question or cause for controversy—the book is far too grand and intricate for that. As I lay out my basic approach to the book, however, I hope others will find some encouragement in learning to read it as Christian Scripture.

Second, and more specific to the work of Manna Gum, I hope to illuminate the Book of Revelation’s powerful critique of violent economic systems and its alternative vision for Christian witness and human life.

How do we read Revelation?

Interpreting texts is tricky business, particularly one as strange as Revelation. But there’s no reason why we should treat Revelation as fundamentally different to, say, the Gospel of Luke or Ephesians. Each book is a coherent whole, seeking to convey a message, and we should be wary of approaching each with our conclusions already decided. Furthermore, in each case we consider the literary context (what kind of text is this and what is it saying?) and the historical context (from what historical situation does this text arise?). Not that these contexts exhaust the meaning of the text, but they do provide a good starting point.

Literary Context

Perhaps part of what makes the Book of Revelation so complex is the fact that it contains at least three genres: epistle (letter), prophetic text and apocalyptic text.

Epistles and prophetic texts are somewhat familiar to us, in part because they are common elsewhere in Scripture. Again, this suggests to us that we shouldn’t take a radically different approach to reading Revelation compared with other texts.

Where Revelation is most strange to us is in its so-called ‘apocalyptic’ aspects. While there are apocalyptic elements elsewhere in Scripture, Revelation is by far the most comprehensively apocalyptic text.

So, what is an apocalyptic text? Defining apocalyptic has been a hot topic in biblical studies for decades, but generally speaking apocalyptic texts are thought to be those that tell a story about a person’s visionary experience. In this story, the world is imagined symbolically. The reason for the symbols is that it forces the audience to look at the world in a different way. This is why the texts are called ‘apocalyptic’—the Greek word apokalyptō means ‘to lift the veil’ or ‘to reveal’, and apocalyptic texts seek to reveal a divine truth to the audience.

Despite the thinking of certain preachers, apocalyptic texts were not about the future, but were written to explain the difficult circumstances in which the people addressed found themselves in their own time. The only reason these texts ever look to the future is to help explain the present and to offer hope. The audience of an apocalyptic text is typically a marginalised or oppressed group in the midst of a traumatic experience. Apocalyptic texts are intended to help them view the world through a different lens so that they can endure their suffering.

So why, then, does apocalyptic literature use such strange symbols? Such a question is likely a product of our own distance from the original audience, both in terms of time and culture. In truth, the language used in these texts was fairly comprehensible to the original audience.

Simply put, Revelation is a text that utilises well-known genres and symbols in order to reveal to its audience God’s perspective on their current situation of suffering and marginalisation. But if the audience was being oppressed, who was the oppressor?

Historical Context

The answer to this question is fairly straightforward: the dominant power in the Mediterranean world at the time of Revelation was the Roman Empire. The entire New Testament originates in a social, political, economic and religious context overshadowed and dominated by Rome, whose empire spread from present-day Britain, France and Spain across to Turkey and Syria and down to North Africa, ruling over approximately 60-65 million people of a diversity of ethnicities and cultures.

Revelation was probably written in the late first century CE under the reign of the Emperor Domitian. In the political system of Rome there were vast disparities of wealth and power. Life was miserable for a great many people not fortunate enough to be in the top 2–3% who made up the elite. This elite class owned the majority of the land and consumed some 65% of its production. They exploited cheap labour with slaves and tenant farmers and imposed tributes, taxes, and rents.

Rome was able to preserve this situation through its military domination. The so-called Pax Romana (Roman Peace) of the period was the result of military coercion and the constant threat of military action. The cost of maintaining the 25 legions (6000 troops each) of the Roman military machine was paid by the taxes mentioned above.

Ruling over this system was the emperor, who was called 'Father of the Fatherland' (pater patriae) and also 'lord' (kurios) and 'saviour' (sōtēr). People were required to have 'faith' (pistis) in him, which meant loyalty or faithfulness. In fact, when a new emperor was crowned, the announcement message was called the 'gospel' (euangelion).

While this is no doubt a vast simplification, it gives us a snapshot of what life may have been like for the audience of Revelation. The problem that they would have faced was not that they believed in a strange religion—Rome was generally tolerant of different religions. Rather, the problem for early Christians would have been that they denied the sovereignty of Rome and the emperor, instead claiming they belonged to a different kingdom, ruled by a different Lord, Saviour and Father in whom they put their faith by means of a different gospel.

In other words, the early Christians experienced periods of persecution because they were a political threat to Roman power and authority. If, as I suggested before, apocalyptic texts were written for oppressed communities, it makes sense that the Book of Revelation would have appeared for a certain community of early Christians. A question that would have been supremely relevant for them would have been, how should followers of Jesus, who was crucified by the empire but raised by God, negotiate Rome’s empire in their daily lives?

How, then, does the Book of Revelation answer this question? This will be the question over the next few instalments of this series in which I’ll turn our attention to some specific texts. As an introduction to Revelation’s message of discipleship, we’ll turn to one’s of the book’s most well-known characters.

The Beast (Revelation 13:1–10)

Revelation’s beast is hardly original. It is borrowed from Daniel 7:1–8 which describes four beasts, with the fourth being the most horrifying. These beasts are metaphors describing successive empires with whom Israel was confronted, as explained in Daniel 7:15–28. Daniel doesn’t identify the beasts and scholars disagree about which empires each represents. One strong possibility is that the beasts symbolise the Babylonian empire, the Median empire, the Persian empire and Alexander's Greek empire respectively.

The specifics are not terribly important for our present purposes. What is important is that, in Daniel, the focus shifts from the beasts to the ‘Ancient of Days’, who kills the fourth beast and takes the authority of the other three away. In the place of the beasts, authority is given to one like a son of man, whose kingdom will never be destroyed.

By the time Revelation was written, the fourth beast in Daniel was interpreted by some to represent the Roman Empire (e.g., 4 Ezra 12:11–30). But Revelation understands Rome differently. It is not merely the fourth beast, but in fact a composite of the four beasts in Daniel’s vision. Daniel’s beasts look like so:

Beast 1: Lion with eagle’s wings

Beast 2: Bear

Beast 3: Leopard with four bird’s wings

Beast 4: Iron teeth and ten horns

The Beast from the sea in Revelation 13, on the other hand, has, ‘Ten horns … And the beast that I saw was like a leopard; its feet were like a bear’s, and its mouth was like a lion’s mouth. And to it the dragon gave his power and his throne and great authority.’ This beast is a compilation of all of Daniel’s beasts.

In other words, Revelation shares Daniel’s use of beasts to describe empires, but Revelation’s Beast is more fearsome, more terrifying. This makes sense of Rome’s power, even in comparison to previous empires.

La Bête de la Mer (The Beast from the Sea), part of medieval

Tapisserie de l'Apocalypse (Tapestry of the Apocalypse).

This Beast emerges from the sea, the traditional place of chaos and death. It has a mortal head wound that has been healed (13:3), recalling the Emperor Nero’s suicide and the ‘Nero Redivivus’ legend in which it was said he would return. The Beast’s number, 666 (13:18), is a construction of Nero’s name by way of the common Jewish practice of the time of assigning numeric values to letters.

Nero had been a particularly brutal emperor, persecuting Christians after having used them as a scapegoat for Rome’s burning in 64 CE. After Nero’s death, the empire had almost collapsed, with four emperors taking the throne within the space of one year. It was the dynasty of the Flavian emperors, including Domitian, which brought the empire back from the brink. In other words, the empire had almost died, but alas came back to life.

It is no wonder, then, that the people are said to worship the Beast: ‘Who is like the beast, and who can fight against it?’ (13:14). This is not unlike Exodus’ claim about Yahweh, 'Who is like you, O LORD?' (Exod 15:11). The Beast seems invincible, even godlike.

But Revelation wants to make the point that the Beast is only a shadow of reality, a kind of parody. It has been resurrected, but it is a sub-par version of the resurrection of the Lamb in Revelation 5. The Beast is a parody of the God of Israel (‘Who is like you?’). And though the Beast utters blasphemies about God (recall Nero’s opposition to Christianity), he will only be allowed to exercise authority for forty-two months (13:5). Why forty-two? In Hebrew symbolism, seven is the number of completeness, while six is just short of that, the number of incompleteness. 7 x 6 = 42. ‘Let anyone who has an ear listen.’

Those who worship this Beast will not have their names written in the book of life (13:8). That is, they do not experience the life given by the Lamb of God, but only the deceit of the Beast.

Then, in Revelation 13:11, there appears a second Beast out of the earth who works to legitimate the first Beast. This second Beast speaks like a dragon, a reference to Revelation 12 where the dragon is Satan. In other words, the Beast is the product of the great source of evil himself. This is Revelation’s damning verdict on the Roman Empire.

Revelation insists that those who seek to be faithful to God must not enter into the worship of the Beast; they must not accept Rome’s version of imperial reality. This is difficult, since those who worship the Beast are given a mark that allows them to buy and sell (13:16–17). The ‘Mark of the Beast’ has been a source of much speculation in certain contemporary circles, but in Revelation the meaning is rather simple: to refuse to acquiesce to the demands of the Empire could have meant social and economic exclusion — how can one buy and sell in their communities if they have been excluded for not worshipping the Beast?

A coin minted during the first century with the image of Nero.

So What?

So, what does all this strange symbolism mean for the way Christians ought to live? Revelation’s description of Rome as a Beast is the heavenly perspective on what is apparently invisible to many humans: Rome is a monstrous, murderous, maniacal entity. The Beast seems especially to symbolise the coercive power and violence of imperial military might.

Revelation seeks to uncover this violence, to unveil the fact that the so-called Pax Romana (Roman Peace) was a sham for it is a peace brought about only through beastly, even inhuman, coercion and violence.

In the midst of all this, Revelation makes the following appeal: ‘Here is a call for the endurance and faith of the saints’ (13:10b). The book is not merely describing Rome’s military power as a beast because it would make a good read. It is describing a terrible reality in its world that must be opposed. Revelation’s is a call to embody an alternative and a challenge to Rome’s way of doing things.

Being such an alternative does not mean starting a rebellion against Rome; Revelation never counsels such counter-violence. But nor is the Christian alternative a form of passivism whereby Christians merely try to accommodate the way things are. Revelation counsels a third way of nonviolent embodiment of the kingdom of God (we’ll have more to say about this in future parts of this series).

This alternative begins not with a particular set of actions, but with seeing things differently — having one’s imagination transformed. As I’ve said, Revelation seeks to uncover reality from a heavenly perspective, to reveal how things really are. This might make us think the book is trying to get its readers to embrace some kind of heavenly escapism. This is not at all the case. The Book of Revelation reveals the very earthy reality of the daily violence and seductions of a particularly brutal political system, one that crucified Jesus. But it also asserts that Jesus was raised — the empire failed to kill him. Rome is not inexorable or inevitable, and, in fact, its days are numbered.

In the meantime, the Christian community is called to endure and resist Rome’s violence and seductions by embodying the example of Jesus, the slain and risen Lamb. This took numerous practical forms [see Edwina’s piece in this edition, for example], all of which derived from a transformed way of seeing the world whereby God, and not Caesar, is in charge. God will eventually judge the world, setting things right; this makes possible a radically countercultural way of living now, in the present.

Our own political system is by no means as openly vicious as Rome. Still, the global systems in which we live brutalise workers, even whole populations, as well as the natural world in order that we in privileged nations might maintain our opulent lifestyles. Revelation’s call to resist violence and seduction is far from abstract. It demands allegiance to Christ in our daily lives. We’ll talk more about what such allegiance might look like in our next instalment where we’ll focus on the ‘Great Prostitute’ in Revelation 17 and its damning critique of imperial economics.

Dr Matthew Anslow is the editor of Manna Matters. He's married to Ashlee and together, with their three young children, they live at Milk and Honey Farm, two hours west of Sydney.