Sri Lanka has been called the land of ‘serendipity’ – meaning a surprising, delightful, unexpected discovery. So it was with me in 1976 when I first visited that country. My visit to the Coconut Research Institute turned out to be the start of an adventure.

I was amazed by the palm itself: that it should produce regular bunches of large fruit all year round and that the fruit itself could be divided into a wide range of products. The husk could be made into coir fibre products; the shell into tools, ornaments, charcoal and activated carbon. Then there was the nutritious juice (water) followed by the flesh which had delicious milk, cream, oil and – potentially – desiccated coconut. No wonder the palm is referred to as ‘The Tree of Life’.

Ten years later, in April 1986, Cyclone Namu tore through the Solomon Islands causing enormous devastation. That same month, the world price of copra dropped to less than half its ‘normal’ price. Deaths in the country from malaria had increased rapidly. Population growth was much faster than the increase in national educational and medical services. I remember thinking that the country was ‘paralytic’ and recalled the story of the crippled man brought to Jesus on a stretcher by four friends. Their way into the house was blocked by a crowd, but with a good dose of lateral thinking, they made a hole in the roof and lowered their friend through it to Jesus (Mark 2:1-5). I prayed then that maybe I could help this nation – possibly through the ‘Tree of Life’, with its wide range of potential products.

In 1991, I attended a conference where a British scientist presented a paper on low-pressure extraction of coconut oil. It described a simple traditional technique for producing coconut oil first observed in Tuvalu. It took me a while to grasp the importance of this work, but in 1992 I was challenged by a village soap maker in Mozambique to come up with a method whereby he could make his own coconut oil on the farm rather than selling his copra to a large factory and buying the oil back. It was a few months later that I experimented with a simple caulking gun: I modified the sealant tube by drilling micro-holes and making sure the piston could move both ways. I mixed some desiccated coconut with a little hot water and stuffed this into the tube and started pressing. Eureka! Oil just poured out onto the floor!

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

|

Top: The Direct Micro Expelling technique provides a cheap and easy-to-use means of village-based production of high-value coconut oil. Above: a four-man team at the drying tables. Photos by Sean Davey. |

This was the birth of what became the Direct Micro Expelling (DME) process:

Direct – quick – pure oil within one hour of opening a coconut.

Micro – small scale (family farm size).

Expelling – extraction of extra virgin coconut oil (EVCO).

With active support from the CSIRO, we built some genuine presses and started field trials in PNG, Solomon Islands and then Fiji. We showed that it was indeed possible to produce a pure raw, virgin coconut oil of superb quality in a village or farm setting using what was effectively indigenous Pacific island know-how. We registered Kokonut Pacific as a company in November 1994 in order to have a vehicle to produce the equipment.

The Company’s vision was, and is, encapsulated in the motto ‘Empowering and Bringing Hope.’ In partnership with local communities, we aimed to improve their lives by building sustainable value chains and revitalising the smallholder coconut industry with appropriate technology. I was fortunate in that I had a full-time research position at the ANU, but that did not provide funds for a commercial operation. Without knowing quite what we were getting into, my wife and I, our eldest son and two good friends in Brisbane provided very modest, totally unsecured, loans to the Company. Our five shareholders were passionate about justice (for people and the planet) and wanted to invest with purpose. I retired from the university in 1997 to follow the dream. In effect, we became a pioneer ‘social enterprise’ before the term came into common use.

Kokonut Pacific was formed as a for-profit company rather than a charity because we believed that it had to be profitable in order to be sustainable. Profits were made, but retained as we grew. We still have the five original shareholders, but later (2013) added an extra shareholder in the form of a charitable trust, the Niulife Foundation (NLF). KP had two parallel strands to work on: first, the supply side, the DME process and the production system; and, secondly, the demand side – the market for the oil produced.

Making Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) at a village/farm level was a totally radical, if not ridiculous, proposition. There was no market for it. Initially we thought that the oil would be used mainly as a diesel-fuel substitute in remote locations. Copra was the only commercial coconut product produced at a village level. This debased raw material was exported for the oil and meal to be extracted in large factories overseas. The farmers never saw the oil or the meal. But the DME units in Fiji and Samoa produced far more VCO than the domestic market could absorb. In order to sustain this new value chain, we had to find export markets for the VCO now arriving from Samoa in 200 litre drums.

At first, markets for this rare, beautiful and healthy oil were very hard to find. Then, almost miraculously, some ‘radical’ nutritional scientists were taken seriously. Early studies on coconut oil were re-examined. Books and articles extolling the dietary benefits of coconut oil were widely published. Over the next two decades VCO has become something of a superfood featured in many magazines and recipe books. When we approached the largest vegetable-oil marketer in Melbourne 2003 with our oil we were told very firmly that there was no such thing as virgin coconut oil. However, as a charitable gesture, the manager bought two drums. Ten years later, they were our largest bulk customer buying six tons quarterly! The demand for VCO ‘took off’! So far, so good.

The challenge for us was to increase the supply of VCO from remote villages to affluent countries. But where? My original prayer was for the Solomons. If the Solomons was ‘paralytic’ in 1986, by 2002 it was ‘quadriplegic’. Ethnic conflict resulted in the RAMSI initiative in July 2003 to restore law and order. Colin Dyer, a missionary who was rebuilding burnt-out schools and clinics in rural locations where others ‘feared to tread’, invited Kokonut Pacific to consider a joint venture. Who would be rash enough to invest in the rural areas of a ‘failed state’? Another step of faith was required – encouraged by the poor widow’s experience in 2 Kings 4: 1-7.

By June 2004, we had set up a joint venture company, Kokonut Pacific Solomon Islands (KPSI). Colin Dyer provided the local contacts and administration for scattered village communities that were taught how to produce DME VCO. Kokonut Pacific (Australia) (KP) provided the equipment, training, technical, logistic and marketing support.

DME VCO is ideal to produce at a farm level. Not only does the producer have pure oil, but the residue is edible for human consumption and – together with the coconut water – makes an excellent stock feed. VCO has a long shelf life – measured in years rather than weeks or months.

We knew that any farm or village-based DME unit operating as a small business entity would perform best if it were a module within a system that provided the economies of scale necessary to enter the international market. The system could have three tiers of actual production units, regional service centres, and then a headquarters’ operation.

The economics of a system will vary depending on the density of coconut plantings, yields of fully mature nuts, farm size, ease of road and/or marine access, size of local markets, distance from export markets and, critically, on the desire of rural entrepreneurs and local communities to engage in this new coconut processing enterprise. Export markets require an assurance of quality. A reputation of having a remote pristine environment is not enough. Annual inspection of farms and VCO producers by an internationally accepted organic certifier became a necessary and expensive requirement which KP funded for 10 years.

The logistics of getting the oil from an isolated village to the export port for consolidation with oil from numerous other producers were, and are, challenging. Key components of the links in the chain include establishing and maintaining good relationships with farmers and producers, technology development and transfer, training, extension, business principles and handling money, communications and logistic support. It was to help facilitate this complex task, we set up the Niulife Foundation (NLF) in 2013 so KP could use its profits more effectively to assist poorer tropical communities to get better value for their coconuts.

One of NLF’s first projects was to help establish the Coconut Technology Centre (CTC) in Honiara. The CTC was registered as a legal charitable entity in September 2014 and an Australian volunteer (Frank Sanders) was engaged to build the basic facility and begin operations. The centre was formally launched by the Minister of Agriculture in June 2015 and is now managed by a Solomon Islander.

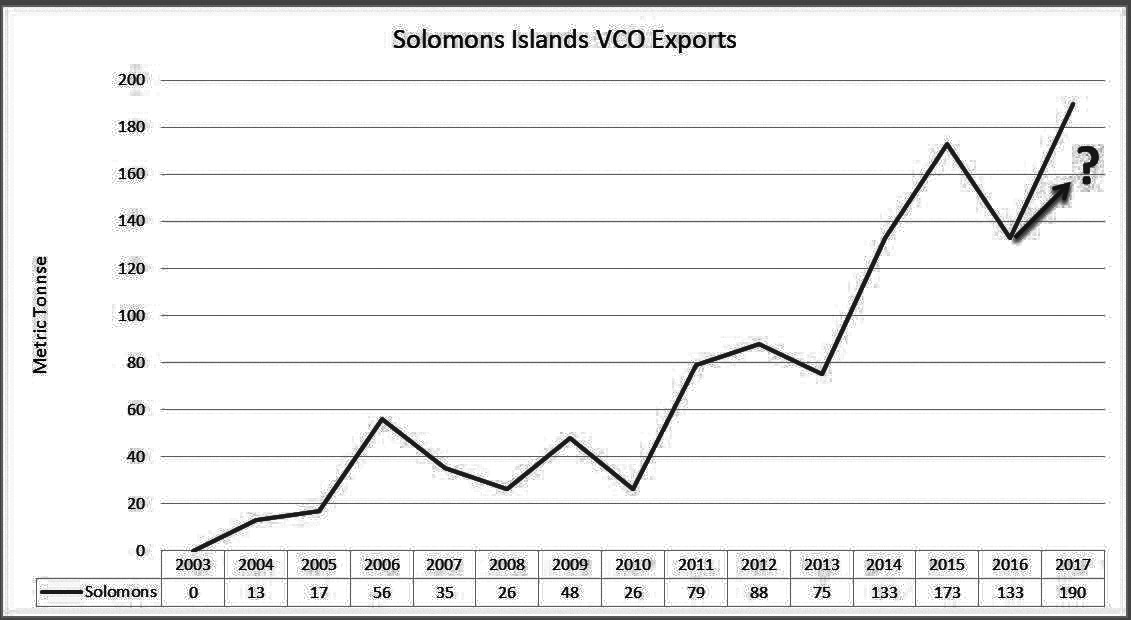

Supply side VCO production is increasing

Our vision was affirmed in 2006 when KPSI won first prize in an international competition mounted by the Asia Pacific Forum for Environment and Development (APFED). Ten years later, KPSI scooped the ‘Prime Minister’s Award’ as Business of the Year. Two other awards – Exporter of the Year and Business Contribution to the Community Award – were also received.

However, a significant biosecurity threat has emerged in the Solomons caused by the invasive attack of the Guam sub-species of the Coconut Rhinoceros beetle (CRB-G). Between 2014 and 2018, the stock of coconut palms in Honiara has plummeted by 73%. The threat of CRB to the islands is potentially dire.

What of the demand side?

VCO production from large-scale desiccated coconut (DCN) factories is now common in Sri Lanka, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. VCO has quickly spread from health food stores to supermarket shelves. Prices have halved! Our overseas bulk oil customers are facing the same challenge from a flood of new cheaper coconut oils entering the market.

KP has responded with a comprehensive rebranding exercise with new labels and updated Niulife website. Radically new retail packaging emphasises the uniqueness of KPSI’s village-produced oil. Our distribution network tells that ‘Trade, Not Aid’ brings benefits to over 10,000 people (farmers, oil producers, their families and neighbours, schools, clinics and churches) by the provision of employment and higher incomes. Communities are healthier, better educated, better dressed and enjoy an improved lifestyle with better homes and a hope for the future. The oil producers receive a price for their oil that is stable and above world market prices. Overall, communities make five times more from coconuts turned into VCO than the alternative, copra.

|

|

.jpg) |

|

|

KP’s ‘Niulife’ brand is trusted as the Australian ‘coconut specialists’. In addition to VCO, KP sells the widest range of coconut products which we source from different countries – from the flesh we sell (Creamed CN, CN flour, DCN) and from the nectar (CN sugar, syrup, vinegars and sauces). This diversification strategy spreads our risks and builds the sustainability of the brand around our core VCO product. We also continue to sell our DME equipment around the tropics.

The dilemma for our joint venture is how to remain competitive in a high-cost island situation. (KPSI) has made great strides in value-adding for the domestic and international markets with superior quality soaps and cosmetic products. It is important that DME VCO producers make their operations more efficient and use as much of the coconut resource as possible (composting husks; making coconut shell charcoal and feeding residual meal to livestock). It is important that the quality of the oil is maintained at high international standards.

As a founder of KP and joint founder of KPSI, I believe that in time middle-class urban Asian consumers will absorb more and more of their own country’s VCO production. There is then enormous potential for VCO exports from the South Pacific to increase. The Solomon Islanders have the coconut and human resources to continue to expand their VCO production and exports. We will continue to support this enormously important initiative. The adventure continues!

We have used for-profit structures to ensure sustainability and enter world trade on behalf of remote communities. This continues to pose enormous challenges. The rewards to the company and shareholders are not from financial returns, but the intangible good will expressed in smiling faces.

For more info see:

|

| Dan and Maureen Etherington, co-founders of Kokonut Pacific. |