It is school holidays. Peter has called to see if the mulcher and whipper-snipper are available. I tell him the whipper-snipper (which we co-own together) is in our shed and he can grab it any time, but the mulcher (which four households co-own) is at Colin and Anthea’s. They are away at the moment, but Greg and Elvira are staying in their house, so he will be able to get the key to their shed. I remember at this point that I need to go around to Colin and Anthea’s to pick up the dog crate, as they took care of our dog while we were away …

Kylie has banged and cut her head quite badly while vacuuming and Dave (on retreat with Jon and Glenn) is away with the car. Kylie calls Colin and Anthea, who come around and do some initial patching up on Kylie’s head, then take care of her son, Shane, while Kylie borrows their car to drive to the hospital. Next day, Kylie needs a car again, so she calls Kim (Colin and Anthea have gone away). Kim says that is fine, but Edie is currently using the car to fetch a load of horse poo, so she will have to get it off her. That night, Kim, Kylie and Edie, and all the kids have dinner together while their husbands are away …

Edie has sent around an email - it is time to put in our bulk orders for Fair Trade tea and coffee. I have to decide whether we order way more coffee this time, or I try to reduce my consumption …

I am building a pergola along the north face of our house. It is a big job and I can’t afford to pay anyone to do it, but I have never built one before. I pick Peter’s and JD’s brains first, then get to work, getting a decent half-day’s labour (and bits of advice along the way) on each day I work, from Peter, Glenn, Colin and Dave. I use a number of Peter’s and JD’s tools to do the job.

---

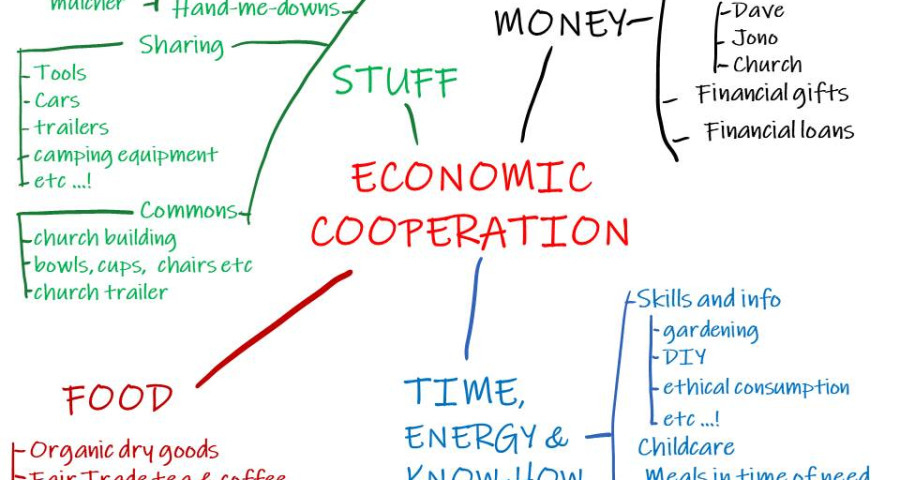

This is the normal week-to-week life and interaction of the Seeds Community in Bendigo. It is not something that has happened by design, but something that has grown entirely organically. It was only recently in one of our evening discussions that we decided to think a bit more intentionally about how we practise economic cooperation, beginning with mapping what we already do. As the piece of butcher’s paper began to fill up, we were gratified to discover that it was quite a lot. This is what our butcher’s paper looked like [see above].

In this article, I want to share a bit about the experience of economic cooperation in the Seeds Community, what it looks like, how it has happened and what we have learnt. The danger with writing an article like this is that it can tend, however unintentionally, to make something seem more impressive than it really is, when in actual fact it has all been rather ordinary and low-key. I am willing to risk this danger because this is a subject that, if it is to go any further, really needs people to be sharing and discussing real-life examples. We have all been shaped as highly individualised consumers and have largely lost the multifarious arts of economic cooperation. For the sake of ourselves and the planet, we urgently need to recover them. And I know from experience that, on subject matter like this, the great need is to get beyond ideas and down to practicalities. This is one modest step in that direction.

What have we done?

Income-sharing

Income sharing is simply where a group of people pool some portion of their income to fund activity they want to see happen. Two people in the Seeds Community (Dave Fagg and myself) are involved in ministry where our wages are paid by raising financial support (Dave for community mission work in Long Gully, me for Manna Gum). This goes far beyond the Seeds Community, but a significant portion of our income, for both of us, comes from within our own community. That is, our community has directed significant portions of income to support the ministries we undertake.

The other key area where we pool income is through our giving to St Matthew's, our local church in Long Gully. People don’t generally think of their tithe or offering as engaging in income-sharing, but that is what it is: pooling money to support a local community organisation. In fact, the local Christian gathering has always been a community of economic cooperation in some way, even if it has largely lost this self-understanding.

Sharing stuff

The informal, ad hoc sharing of stuff has been a notable part of our community life. The range of things shared spans virtually the whole gamut of household goods, including cars, trailers, tools, garden equipment, kitchen equipment, camping and recreation equipment, books and the list goes on. Of particular note has been the readiness to make our cars available to each other – something of enormous practical value at various times. Also of note is the circulation of hand-me-downs in kid's clothes and assorted household items.

|

|

|

A mulcher is super-handy to have, but a bit too big and expensive to own on your own.

|

Co-ownership

For some items, some households have decided it makes more sense to split the cost and share the ownership. Once again, this has happened on an entirely ad hoc basis, stemming from particular need and circumstance, not any plan. Two households have owned a mower together, two own a whipper-snipper together and four households have pitched in to buy a decent mulcher, something extremely handy every now and then, but not enough to warrant buying one yourself. Interestingly, these co-owned goods have been just as much a part of the sharing economy discussed above, available to other non-owners.

Cooperative purchasing

Members of the Seeds Community all share an ethic of responsible consumption, trying to prioritise organic, Fair Trade, minimal packaging, Australian-owned and made and, where possible, local. But it all takes time and energy and generally costs more, and most of us are on below-average incomes. Edie has taken it on herself to organise the cooperative purchasing of bulk organic dry goods (flour, rice, oats, dried fruit, etc) and bulk Fair Trade tea and coffee (see Manna Matters, Advent 2015). This involves pooling our money together for the purchase and delivery and getting together once a quarter to divvy up the goods according to orders. The trick is in coordinating the orders and the purchasing, which Edie, armed with an Excel spreadsheet, has down to a fine art.

We also join forces periodically to buy meat from local sources that have been kind to the earth and kind to the animals. Once again, this is expensive to do and hard to find, but when one of us finds something we have generally emailed around others to take orders for a bulk purchase and pick-up. Kim has gone for chickens from Hand to Ground in Kyneton, Kylie has sourced lamb from her Mum’s property, also in Kyneton, and Ali and Di, members of the St Matthew's community, have sold pork raised from their property out of town. Making these bulk pick-ups work has also involved sharing cars and Eskies.

Shared labour, skills and care

Another of the key features of our economic cooperation has been the sharing of time and energy, know-how, muscle and acts of care. This has been so intrinsic and natural to our community life that no one really thinks of it as 'economic' sharing, but it nevertheless amounts to something of significant material and practical value. It can take the form of child care, caring for pets and gardens while on holiday, sharing home economy and handy-man skills and know-how, working bees in someone’s garden, help with big projects and the provisions of meals in times of sickness or distress. Of all the forms of cooperation, these sort of activities most convey the sense of others being there for you.

|

|

|

St Matthew's Church: a 'local commons' in Long Gully that is supported by community income-sharing.

|

Commons

‘The commons’ refers to goods owned and/or managed by a community. St Matthew’s Church in Long Gully, which, in its current form, was started by the Seeds Community, has functioned as something of a commons. As well as being a place of worship and venue for a whole bunch of different community initiatives and organisations, it has also become an economic good both for its members, and for the local community more broadly. The St Matthew's community (which extends beyond Seeds members) is an independent congregation, with no paid staff and a flat structure, that manages a building and property owned by the Anglican Diocese of Bendigo and very graciously made available to us. That is to say, the church only exists by the ongoing will and efforts of its members, so there is a very high level of ownership and participation. Consequently, it has just seemed natural and sensible that when one of us has a function or party on, we borrow cups, bowls, plates, chairs and tables from the church. Or sometimes we use the building itself. Moreover, with its pizza oven, garden, amphitheatre and adjoining hall, the church has been an attractive venue for other locals to hold the odd birthday party at little or no cost. The church also owns a trailer that has been made freely available to virtually anyone who asks (whether members of the community or not). Once again, there is no system, set of rules, or log book for any of this; it all just happens with a high level of trust.

How did it happen?

As I have pointed out a number of times, none of this happened by design, but has rather evolved organically out of the life of the community. But there are a number of preconditions that have inclined us in this direction and others that have allowed it to be possible.

- As a covenanted intentional community [see box below] we are already predisposed to think of ourselves as a ‘community’ - that is, people who are sharing a common life - and we have invested a certain level of trust and hope in that community.

- We all in some way accept that following Christ has implications for our material lives and are all concerned about the impacts of the consumer economy upon people and the planet.

- Part of the Seeds Covenant is to live in the suburb of Long Gully, so we all live within an area 1.5km across. Geographical proximity makes possible many acts of sharing and cooperation which, otherwise, would be much harder to accomplish.

- Most of us work part-time and have therefore chosen a level of income-constraint on our lives that gives us a real practical incentive to think about how we can economise through shared action.

Evaluating our experience

When we reflected on our experience of this economic cooperation, the strong consensus was that it had been uniformly positive across a number of fronts.

- It has enriched and deepened our experience of community. The material and practical value of this sharing takes the experience of community beyond simply something we choose, to be something we come to depend upon, and something through which we have come to experience a significant level of care and support.

- Economic cooperation has required trust, but doing it has also built trust.

- Although we have not quantified the economic value of our economic cooperation, there is little doubt that its value to the bottom line of our household budgets is significant.

- The seemingly low-key, but creeping, practice of sharing goods has helped us to gradually learn to loosen our grip on our possessions.

- Although our economic sharing has largely arisen from within the Seeds Community, it has not been exclusive to it, but has overflowed into the broader Long Gully community, drawing other people into it and opening up resources to them that they otherwise did not have access to.

What have we learnt about economic cooperation?

- The local Christian gathering is a ready-made technology and site for economic cooperation, if only we can tap its potential. I am a member of the New Economy Network (see Manna Matters, Nov 2018) which involves all sorts of creative and ingenious ways of fostering a ‘sharing economy’, but all of it is trying to make up for the absence of community. We have found the local Christian community to be a place where it can take place naturally without fancy platforms or legal structures and one which can easily leak into the broader community.

- We all acknowledged that reciprocity has been critical to the positive and deepening nature of our economic cooperation – if it were one-sided, it would not last long. But ...

- Not accounting reciprocity has also been critical to the positive experience of it. If we tried to count and keep track of who had given what, it would destroy the graced experience and the willing spirit that sustains it.

- Responsibility for other people’s stuff is critical: treat other people’s stuff with greater care than you would your own, 'fess-up when something has gone wrong and fix it where you can.

|

.jpg) The Seeds Community

The Seeds Community