.jpg)

Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moth and rust do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also. (Matthew 6:19-21)

It’s happened to all of us, in some form or another. Your heart sinks as you hear a ripping sound, feel an unexpected tug where your favourite jacket has caught on a branch. Hoping you are wrong, you shrug off the garment to check the damage. Sure enough, there is a large hole torn in the fabric.

The Bible continually warns us not to become attached to material possessions. Love of money and possessions keeps us from loving God and humans are inclined to love money and possessions too much, when they ultimately mean nothing:

I have seen a grievous evil under the sun: wealth hoarded to the harm of its owners... Everyone comes naked from their mother’s womb, and as everyone comes, so they depart. They take nothing from their toil that they can carry in their hands. (Ecclesiastes 5:13, 15)

|

|

|

Moth and rust may destroy… |

Moth and rust may destroy our material possessions, but considering them disposable spiritually does not mean considering them as disposable physically. Rather, an effort to conserve and repair our possessions recognises the value of the God-given resources that went into their production.

If you’re new to making repairs which require more than a little super-glue and hope, or sending the work out to be done by someone else, I have some news: mending is hard work. In many cases, it would be easier to get a new thing.

Even those — including Christians — who intellectually understand the urgency of the climate crisis, and the need to take actions globally and individually, baulk at many of the personal privations required.

Then he [Jesus] said to them, 'Watch out! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; life does not consist in the abundance of possessions.' (Luke 12:15)

The practice of mending is a great opportunity to reflect on one’s attitude to material things. Our things are really God’s things and caring for them is caring for His creation.

Choosing to make repairs is often a sacrifice, of time even more so than money. It is fast and easy to purchase something new. It takes thought to decide how best to mend something. It takes effort to understand how it works and can be made to work again. It takes dedication to find the tools and materials to mend it effectively. It takes time to effect the repair.

Taking that time to sit down and care for our possessions, doing that work, can be an act of discipleship. On a very tactile level, mending demonstrates many of the values by which we are called to live as followers of Jesus.

Caring for creation

|

|

|

A twist of wire replaces a problem bolt on this chicken feeder. |

Mending is, at its heart, about conservation of resources. To keep a broken item serviceable is to get more use out of the money we paid for it (our personal resources), as well as the energy embodied in its original production (the planet’s resources). And all of these resources are gifts from God. Appropriate use of these resources is therefore part of our job as stewards of God’s creation.

The practice of economy, or frugality, is essentially balancing the consumption of resources involved in an action in order to achieve the least waste. The climate crisis has tipped these scales, making it necessary to put more weight into the conservation of our planet’s physical resources than ever before. Beside the increasing importance of keeping physical waste to a minimum, expenditure of time or money on repairs are dwindling considerations. The effort it will take to sew a patch on your favourite jacket is easily outweighed by the benefit of keeping it out of landfill.

Countering a culture of indulgence

To some, a noticeably mended item is a bit of an embarrassment. Long before social media distilled the concept into a noxious hard liquor, it has been a cultural imperative to continually demonstrate one’s personal wealth and supposedly resulting happiness. In such an atmosphere, any indication of poverty (or less-than-ideal wealth) must be swept under the rug, and the perceived inability to replace something broken falls into that category.

As Christians, we are called to reject this world full of ‘the desire of the flesh, the desire of the eyes, the pride in riches’ and instead let our actions shine as lights in the darkness (1 John 2:15-17). Choosing to make repairs, especially those which will be on display (such as the big patch on your favourite jacket), is therefore a countercultural action. Visible mending can be a powerful statement to others of one’s priorities as a follower of Jesus.

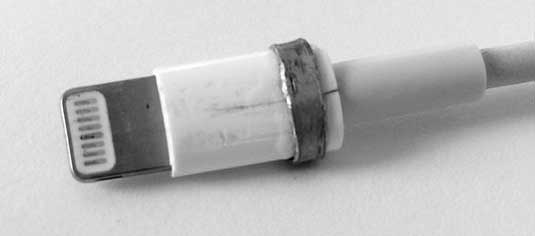

A metal ring ensures this high-use item stays functional as long as possible after mending.

Service to others

|

|

|

This well-loved dress has been extensively repaired multiple times and has finally been retired to garden-and-garage duty. |

There are several ways to serve others through the practice of mending. The most obvious, direct act of service is to employ one’s repair skills to help others with their own repair needs, especially those whose circumstances mean it will have a greater impact on their health and comfort. This kind of act of service is a central part of living in a community as Christians. Performing repairs for others is only one aspect of serving others directly through mending. Repair mavens usually have a stash of materials and tools to use and the provision of these is a valuable service to those without them (and almost always a more economical way to make a repair). And obviously, passing on one’s skills is a gift which keeps giving.

But a commitment to mending also serves people we may never even meet: the global poor who stand to lose the most and quickly from the devastation of a changing climate. Wealthy countries are able to overconsume to such a degree partly because others have so little, and consuming less is one of the (sadly, many) necessary steps toward an equitable and sustainable distribution of resources for all. And every action which slows or lessens the inevitable impacts of climate change aids those people and regions with less ability to deal with the deadly effects we are already seeing and will only see more of in the future. This group probably includes the people who sewed your favourite jacket. Sustainable practices are now and increasingly one of the most powerful ways we can ‘share with God’s people who are in need’ (Romans 12:13).

Redemption

|

|

|

One of many repairs to the author’s favourite jacket. |

The biblical metaphor is one of washing away sins, but the restoration of something considered rubbish (even to an imperfect state, which is where the mending metaphor falls short), is a moment to meditate on God’s surpassing grace. It may only be a jacket, but an unwillingness to discard the worthless and an appreciation of the value of all things God has created are attitudes to nurture as we seek to imitate Jesus. The sacrifice of time and money required when making repairs for others and the planet’s future is an everyday opportunity to train ourselves to put aside worldly desires.

Mending can be hard work, but it is important work. It’s all too easy to stuff that jacket into the landfill bin (it’s unlikely to be compostable) and purchase a new one. But to do so ignores the pressing need to conserve the planet’s resources in any way we can. Choosing to repair and continue to wear the jacket will demonstrate to others your commitment to care for God’s planet and people, at the cost of personal prestige in our greedy, showy culture. The process of mending it provides an opportunity to bring to life on a small scale the values we seek to embody as followers of Jesus. Conserving our earthly goods does not necessarily indicate a harmful love of possessions. Storing up treasures in heaven may mean mending things which are here on earth.

Phoebe Garrett is an inveterate maker of things, with a particular interest in textiles and adapting historical craft techniques to bring about a greener future. She has a degree in ancient history and is currently studying weaving.

.jpg)

Repaired hinges on a sewing machine case.