The Whore Babylon, Revelation 17:1-18 by Matthias Gerung (c. 1500-1570), c. 1530-1532.

Part 2: The Beauty

The Book of Revelation is, as I mentioned in the previous instalment of this series, complex, confusing, and controversial. In that article, I discussed how we might read such a text, outlining what I think are its central historical and literary dimensions in order to provide some context for reading it. I suggested that the book, which was written to communities of early Christians facing oppression and marginalisation, is ‘a text that utilises well-known genres and symbols in order to reveal to its audience God’s perspective on their current situation of suffering and marginalisation’.

From this starting point, I also looked at the figure of the Beast in Revelation 13, showing how it relates to certain Old Testament texts as well as the Roman imperial context of the time. I argued that the Beast represents the military might and violence of the Roman Empire. Revelation’s purpose for using such imagery was to call its audience to endure and resist such violence and to give their allegiance not to the Beast but to Christ, who was crucified by such beastly brutality but was raised from the dead.

In this next instalment, I wish to turn our attention to the figure of the ‘Great Prostitute’ in Revelation 17–18 and the economic critique it raises.

A Disclaimer

Revelation’s negative use of the image of a prostitute has, in some circles, been controversial for its patriarchal and sexist depiction. Feminist biblical scholar Tina Pippin claims the disembodiment of the Prostitute in Revelation 17:16 ‘points to the ultimate misogynist fantasy!’ Pippin’s point is that these images can be quite dangerous, particularly in the hands of men who can exert power over the bodies of women. Howard-Brook and Gwyther point to the example of the church’s burning of women as ‘witches’ as a consequence of taking such images literally as the word of God.

It will not do, then, for a male like myself simply to say that this language was a product of its time. This would be to pass over, and even excuse, the real pain, violence, and degradation that many women across the world have experienced because of the use and abuse of such scriptural passages.

I wish to begin by acknowledging this pain. Without excusing the problems and historical effects of the text, I hope to show that the images of women used by Revelation were not produced with the intent to legitimise violence against women. Ultimately, the image of the Prostitute in Revelation is not about women at all — as we shall see, the image represents a corrupt city and empire.

The Great Prostitute (Revelation 17:1–14)

In terms of the text itself, Revelation describes the ‘Great Prostitute’ as being,

seated on many waters, with whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication, and with the wine of whose fornication the inhabitants of the earth have become drunk. (17:1–2)

That she is seated on many waters is important. The sea was the paradigmatic symbol of death and chaos throughout Israel’s history (e.g., Noah’s Flood, Exodus’ Red Sea, Jonah’s journey). In a sense, the Prostitute is seated on death itself, the place from which the Beast emerged in 13:1.

The Prostitute is also ‘clothed in purple and scarlet, and adorned with gold and jewels and pearls, holding in her hand a golden cup full of abominations and the impurities of her fornication’. In other words, she is obscenely rich and luxurious and her golden cup is the exact opposite of the golden bowls in heaven (5:8) — the bowls hold the prayers of the saints, but her cup holds abominations.

Further, on the forehead of the Prostitute is written ‘a name, a mystery: “Babylon the great, mother of whores and of earth’s abominations.”’

What is Revelation’s author trying to achieve with such imagery? The reference to Babylon is reasonably clear: Babylon was the greatest empire of the ancient world and had become the typical, paradigmatic image of empire in Israel’s tradition. The prophetic sections of the Old Testament denounce heavily the political and economic tyranny of Babylon (see, for example, Jeremiah 50:23–27).

In Israel’s literature, Babylon eventually came to represent all empires opposed to God. For example, most biblical scholars agree that ‘Babel’ in Genesis 11 is an allusion to Babylon (in Hebrew, Bāḇel is the word for Babylon). Babel’s universalising project was thwarted because it was an attempt by humankind to construct an idolatrous empire.

By the time of the late first century CE, Babylon had become a label used in Jewish and Christian circles to refer to Rome (see for example 4 Ezra 3:1–2, 28–31; Sibylline Oracles 5.213–218). One of the reasons for this was probably that Rome, like Babylon, had destroyed Jerusalem and its temple.

It is not difficult to see, then, that this Prostitute in Revelation, who is said to be ‘Babylon the great’, represents the Roman Empire. This is further evidenced by the fact that the Prostitute is said to sit on seven mountains (17:9), a well-known reference to Rome, which was built on seven hills. Rome was, after all, the dominating political reality in the world of the New Testament.

The Siege and Destruction of Jersualem by David Roberts (1796-1864), c.1850.

The Prostitute as Luxury and Economic Exploitation

Like the Beast, the Prostitute is not simply a generic depiction of the empire. Rather, it is an image that emphasises certain of the empire’s characteristics.

If the Beast represents the violence and coercive power of Rome, then the Prostitute, with her ornate clothing and luxurious seductiveness (17:4), represents the economics of the empire that seduces the imaginations of the people, particularly the ‘kings of the earth’ who fornicate with her (17:2).

We are told of the Prostitute that by her the inhabitants of the earth have become drunk (17:2), and that even John, when confronted by her, is moved to ‘marvel greatly’ (17:6b). The Greek word for prostitute is porneuō, the same word used in the Greek version of Exodus 34:15–16 where the children of Israel are warned not to ‘whore’ after the gods of the surrounding nations.

The issue in Exodus is not sexual immorality, but the people’s idolatry and thus the selling out of the radical message of YHWH, which was distinct from the practices of the other peoples who surrounded the Israelites. As Howard-Brook and Gwyther point out, idolatry was not merely about falling down before this statue or that tree — it was about adopting a cult and culture that was at odds with the covenant YHWH had established with Israel.

This covenant was, at its core, a way of life in faithfulness to the character of YHWH. One of the central concerns of the covenant was economics — the Israelites are, again and again, commanded to treat each other fairly in their economic dealings.

One of the ways that Israel in the Old Testament was most unfaithful was in its constant entering into alliances with neighbouring empires for protection, thus abandoning their covenant with YHWH. These alliances were both military and economic. That is, they were trading alliances (e.g., Isaiah 23:15–17; Ezekiel 16, esp. 26, 28–29).

Israel, in making such alliances, was being seduced into economic relationships that were contrary to its covenant with YHWH. By connecting Israel’s past covenant unfaithfulness with the Prostitute, Revelation’s point is reasonably clear: those who capitulate to the Prostitute are committing the same idolatry that Israel had been warned against. Indeed, the entire world has become drunk with the intoxicating and hypnotic seduction of the Prostitute, that is, with imperial economics that conflict with the will of God. In other words, the people have given themselves to a lord other than God, namely the Roman economic system under Caesar.

The Immorality of Kings and Merchants

This is why Revelation goes out of its way to indict the ‘kings of the earth’ (17:2; 18:9) and ‘the merchants of the earth’ (18:11–13) — they are the ones who benefit from the seduction of the Prostitute, from the oppressive imperial economic system.

When it is said in Revelation 18 that Babylon (the Prostitute) is fallen, the kings of the earth ‘who committed sexual immorality and lived in luxury with her’ weep and wail (18:9) and the merchants ‘weep and mourn for her, since no one buys their cargo any more’ (18:11).

What is Revelation talking about here? Why do the kings of the earth and the merchants weep at the demise of the Prostitute? These extremely powerful members of society were those who had become wealthy because of the oppressive economic system in place in the empire.

It is helpful to have some background into this economic system to fully comprehend why Revelation might be so antagonistic toward it. While it is not possible to provide a comprehensive explanation, a basic description will aid our understanding.

The Roman Empire was what social scientists call an advanced agrarian society. Such societies came about in part through the invention of certain agricultural technologies, such as ploughs, which made possible surplus production. Surpluses allowed for trade and permanent settlement to occur. It also allowed for the existence of an ‘exploiter’ class, those who could coerce from agriculturalists the payment of a certain portion of produce.

|

|

|

A Roman sestertius minted under Vespasian (69-79 AD) depicting the goddess Roma seated upon seven hills. |

As time went on, the exploiter class gained more wealth, and thus the power to employ more coercive tactics, such as standing armies. The agriculturalists, on the other hand, became a peasantry. With the rise of elite bureaucracies that were necessary to support this system, the wealthy could begin to keep records, such as debt, and thus debt became perpetual.

Eventually, these exploiting elites became so wealthy that there began to be a demand for rarer luxury goods. This necessitated the creation of a merchant class: people who would travel between settlements transporting luxury goods and selling them for high prices. They would typically buy these from poorer artisans for low prices and sell them to the elite for much more.

In short, advanced agrarian societies were those in which a tiny fraction of the population lived in luxury at the expense of the vast majority, who lived a life of subsistence. The elite worked out numerous ways of extracting all surplus from the peasantry, leaving them with just enough to survive.

The Roman Empire was such a society. Everyone from Caesar and his bureaucracy down to the more well-off merchants made a killing from a system that heavily taxed the majority of rural peasants, leaving them in poverty and constantly at risk of many afflictions and dangers.

It is no wonder, then, that the kings and merchants weep at the fall of Babylon, that is, the Roman Empire and its economic system. Revelation 18:14–17a says:

‘The fruit for which your soul longed

has gone from you,

and all your dainties and your splendor

are lost to you,

never to be found again!’The merchants of these wares, who gained wealth from her, will stand far off, in fear of her torment, weeping and mourning aloud,

‘Alas, alas, the great city,

clothed in fine linen,

in purple and scarlet,

adorned with gold,

with jewels, and with pearls!For in one hour all this wealth has been laid waste!’

If that system were to fall apart, it would indeed be the kings of the earth and the merchants who would weep. After all, they are the ones who have become rich from it. In Revelation 18:11–13 it is said that,

No one buys their cargo any more, cargo of gold, silver, jewels, pearls, fine linen, purple cloth, silk, scarlet cloth, all kinds of scented wood, all kinds of articles of ivory, all kinds of articles of costly wood, bronze, iron and marble, cinnamon, spice, incense, myrrh, frankincense, wine, oil, fine flour, wheat, cattle and sheep, horses and chariots, and slaves, that is, human souls.

This list is representative of the trade in commodities at the time, both the luxuries (gold, jewels etc.), but also the staples of life (oil, flour, wheat, cattle) — Babylon extracts everything from the entire earth, even human persons.

This is the very system that Revelation critiques when it portrays it as a Prostitute.

The Truth About the Prostitute

It is no surprise that the Prostitute is said in Revelation 17:3 to ride on the Beast — John is aware that the exploitative economic system of the empire is achieved and maintained only by the presence of the Beast, Rome’s imperial military and political power. We might remember from the previous article in this series that the ‘mark of the Beast’ symbolises that those who have not given their allegiance to the Beast, the military power of Rome, are not permitted to participate in the economic system. The two systems are intimately related.

The imperial economic system is also held in place by the myths and propaganda controlled by the elites. The nations are indeed drunk on the Prostitute, hypnotised by her seductive myths. She offers them a golden cup, and they drink deeply, to the point of intoxication.

But John’s critique is devastating: the cup offered by the Prostitute, despite its seductiveness, is filled with the wine of her impurities. This includes, according to Revelation 17:6, the blood of the saints — the blood of the witnesses of Jesus. The Prostitute may seduce the inhabitants of the earth — indeed, even John is captivated at first (17:6b–7). But the heavenly perspective on her is that her charms are fraudulent, her ornaments are illusions, and she is destined for destruction

'Come Out of Her, My People!'

|

|

|

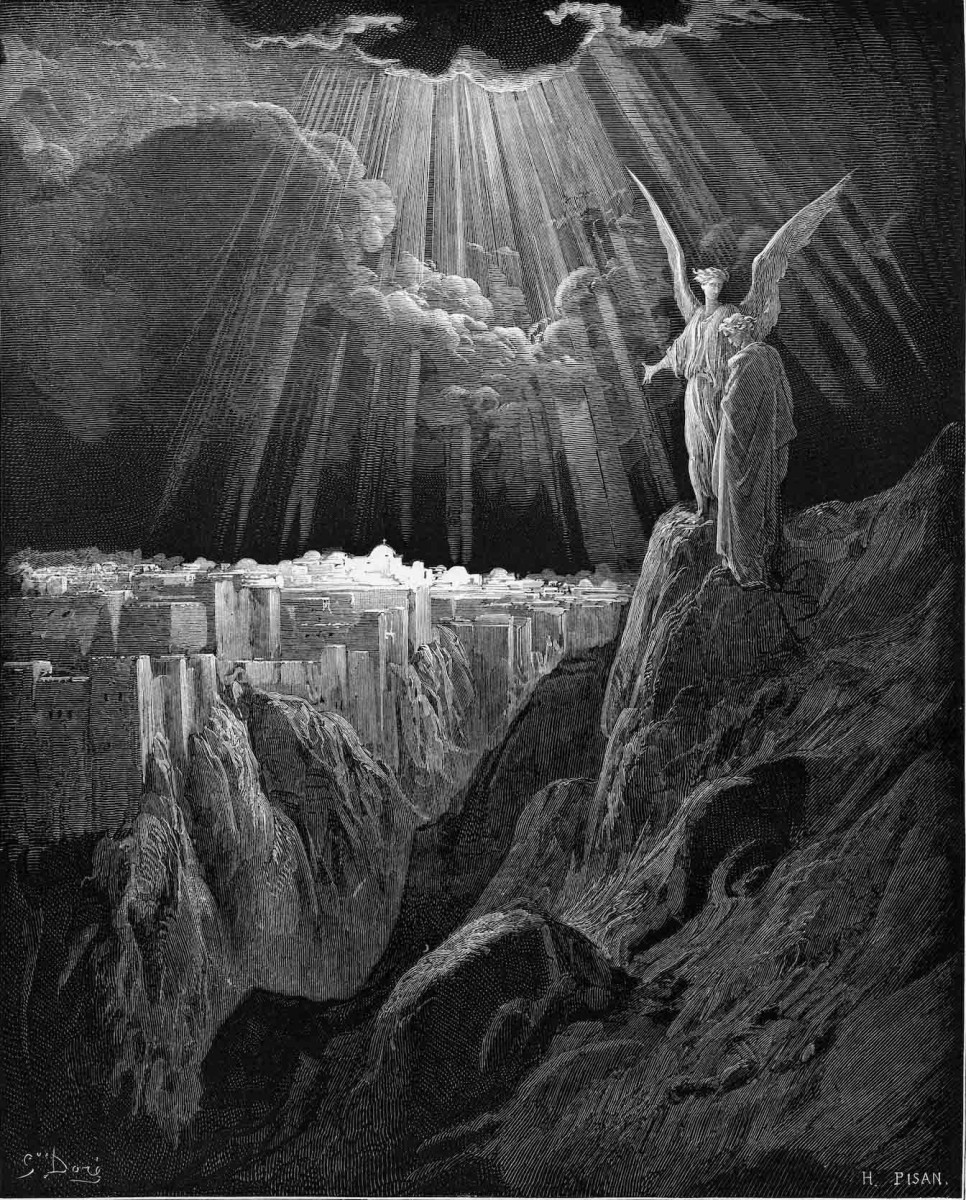

The New Jerusalem by Gustave Doré, 1865. |

Revelation’s warning is to avoid the seduction of the Prostitute, who will ultimately come to ruin. Unlike the kings and the merchants, who fornicate with such exploitative systems, Revelation’s audience is called not to drink from her cup, but to resist her oppression.

This was apparently a real issue for Revelation’s audience. Even if one didn’t like the economic system of the Roman Empire, you were nonetheless compelled to place your faith in it. It was easier to accommodate the empire than to resist; to resist was to risk much. The Prostitute is drunk on the blood of the saints for a reason (17:6) — Rome would not allow a group of misfits who followed an unknown crucified prophet from some backwater province called Judea to create instability in its empire.

Nonetheless, the call of God in Revelation is this: ‘Come out of her, my people, lest you take part in her sins…’ (18:4).

The sexual euphemism is disquieting, perhaps because Revelation’s message is drastic. Though the kings and merchants of the earth weep and wail when Babylon falls, those who have come out of her have no need to weep. Revelation calls the people of God to continue to resist the oppressive and exploitative economic system of Rome. It also warns those who have colluded and compromised with Rome to get out of her now.

As Revelation goes on, we find that the people of God are not merely called to come out of Babylon; they are also called also to come into the New Jerusalem. This is not a call to move geographically. Rather, it is a call to Revelation’s audience to discern the true character of Babylon/Rome and to distance themselves from its seduction by embracing a new way of life. In other words, they are to give their allegiance to an alternative to Rome — God’s kingdom of justice and peace — and to create alternatives in fitting with this kingdom.

Despite the vast differences in experience between the original audiences of Revelation and modern Christians, it is not difficult to draw parallels between the demands placed on them and on us. Today’s global economic system is more obscene and filled with more baubles and trinkets than the author of Revelation could ever have imagined. Revelation’s warnings against being hypnotised by the ‘Prostitute’ are perhaps more relevant than ever.

We have not the space here to proceed into an in-depth critique of our own economic situations in light of Revelation’s message. I trust, though, that this explanation of the book’s economic critique will spawn hearty reflection and conversations. In the next and final instalment of this series, we will turn our attention to Revelation’s alternative to the Beauty and the Beast, namely its image of the slain Lamb.

Until then, may you continue to wrestle with the implicit question posed by the Book of Revelation: How can the Church truly be the Church in the face of a powerful and seductive empire?

Dr. Matthew Anslow is Educator for Lay Ministry in the Uniting Church Synod of NSW/ACT. He’s married to Ashlee and, together with their three young children, they live at Milk and Honey Farm, two hours west of Sydney.