|

|

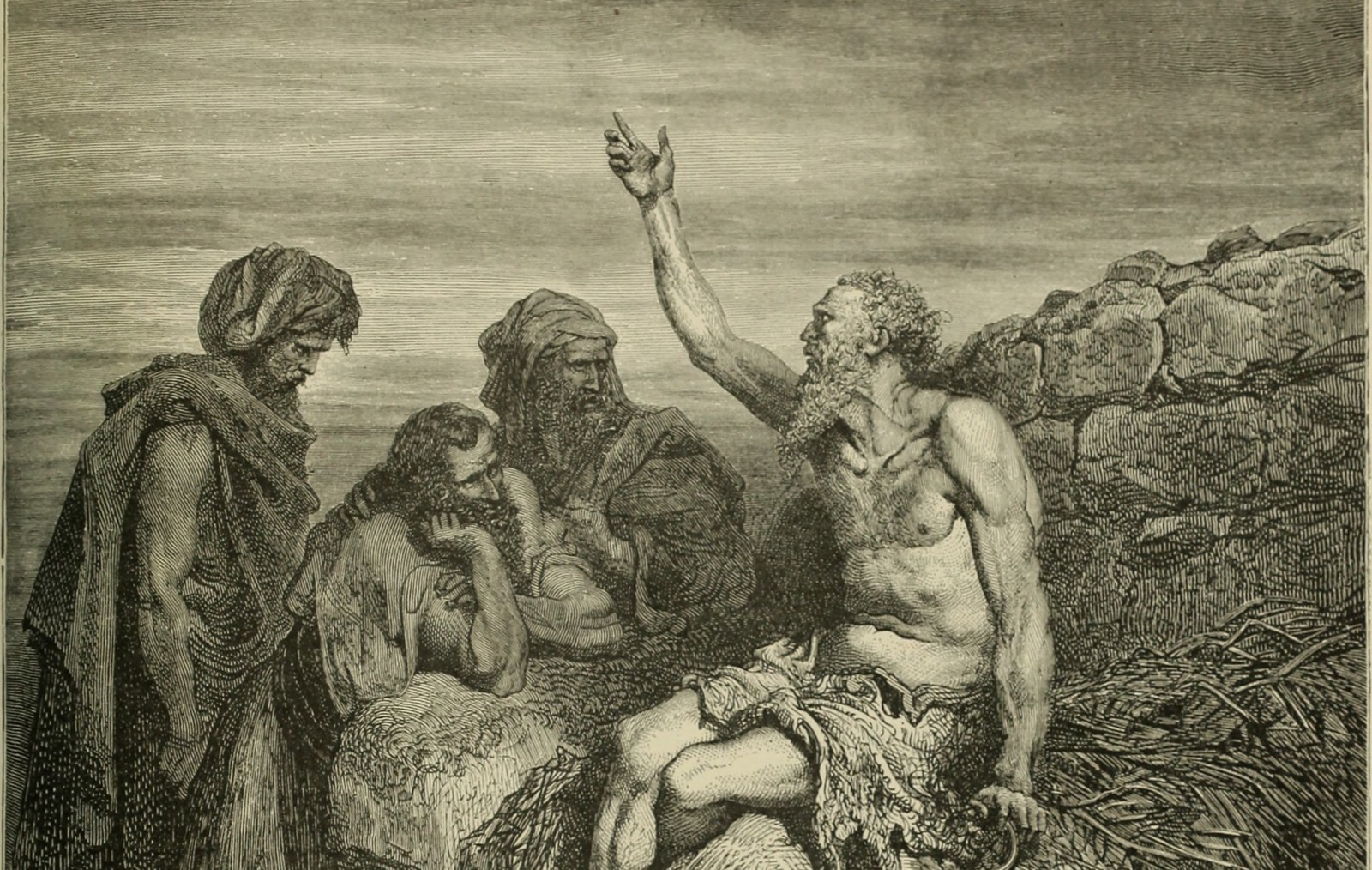

Job's Three Friends Come to See Him in His Affliction, by William A. Foster, 1891. |

In part one of this series we saw how the wisdom writers of the Bible observed life in God’s creation has a particular pattern and order to it: this world is one in which things tend to go certain way. ‘The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises’ says the Teacher in Ecclesiastes, while ‘[t]o the place where the streams come from, there they return again’ (Ecc 1). Human affairs similarly exhibit their own regularity:

A gentle answer turns away wrath,

but a harsh word stirs up anger (Prov 15:1).

While such proverbs are never guarantees, the way of wisdom involves the skill to identify the general pattern and to act accordingly. Simply put, wisdom means making our lives match reality, properly understood. If we do this, we shall walk the straight path: the path of justice, of prudence—of life itself.

But there is a tension here. While the physical and relational order of the cosmos indeed reflects the goodness—and wisdom—of its maker, there are other regularities, too:

If you see the poor oppressed in a district, and justice and rights denied, do not be surprised by such things; for one official is eyed by a higher one, and over them both are others higher still (Ecc 5:8).

Something is amiss. Even the Book of Proverbs, easily the most confident and upbeat of the wisdom books, is not ignorant of this tension, noting things like:

The poor are shunned even by their neighbours,

But the rich have many friends (Prov 14:20).

This is also the way things tend to go. Importantly, as we saw in part one, this is not necessarily an endorsement of the rich, and their wealth is not a reliable indicator of ultimate blessing or wisdom, rather:

Better a poor person whose walk is blameless

than a rich person whose ways are perverse (Prov 28:6).

This is not the place to discuss why good people experience poverty, oppression, or suffering, while ‘the wicked’ might seem to be thriving. We may well cry out in anger or despair at the apparent injustice of it all. Perhaps our words have echoed Job’s in the midst of his pain:

It is all the same; that is why I say

‘[God] destroys both the righteous and the wicked…’ (Job 9:22).

Curiously though, no biblical wisdom writer feels the need to give a thorough answer to why even the wise or righteous person finds suffering or difficulty in this life. Indeed, none of them conclude we should give up on wisdom, even if blessing feels far from us. Instead, the wisdom books are far more concerned with whether we have our foundations right and our priorities in order: if we focus on these, we will be best placed to live skilfully in a world where we are not the master. Wisdom positions us to live well, come what may, and to avoid many of the traps into which the foolish or ignorant person so easily falls.

And there are traps. The ignorant (or “the simple”) fall into them for lack of understanding or discipline: they either don’t see them or don’t know how to avoid them. The foolish and the wicked, on the other hand, are the most lost: fools are those who have hardened themselves against wisdom, even to the point of taking pleasure in evil. Fools walk into life’s traps because they do not believe they are traps. Each of us acts foolishly when we decide life is found amid what are, in reality, snares of death.

|

Thorns and snares

The endless cycle of idea and action,

Endless invention, endless experiment,

Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness;

Knowledge of speech, but not of silence;

Knowledge of words, and ignorance of the Word.

All our knowledge brings us nearer to our ignorance,

All our ignorance brings us nearer to death,

But nearness to death no nearer to God.

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

(T. S. Eliot, Choruses From The Rock)

Speech, motion, and information: the sheer volume of these things threatens to crowd out wisdom. It can be easy to lose sight of life in all the living and the doing. As E. F. Schumacher questions of the modern situation, ‘We know how to do many things, but do we know what to do?’ The wisdom literature is given to help us navigate the often bewildering and persistently complex context in which we must try and live. The sages attempt to pierce to the heart of things to help us discern what to do, and how to live, that we might skirt life’s pitfalls. Some of these are more pronounced than ever, while others are perennial perils. Below are three such traps into which we risk falling.

Trap 1: “There’s not enough to go around”

Despite the incredible efficiencies of our digital age, it doesn’t always feel like this translates to more left over. The shift to e-mail in the 2000s, for example, initially promised immense time savings, but instead, the ease of the new format means we write (and are expected to write) and receive (and are expected to read) more and more letters every week. What’s more, new technologies are always being developed: we have to keep up just to stay on top of things—did you know e-mail is the new snail mail? The world moves so quickly; everyone’s so busy—where does all the time go? In such a fast-paced life, it’s easy to feel like there’s just not enough time. Some proverbs even seem to encourage a life of constant busy-ness, praising diligence and strongly warning against idleness:

A little sleep, a little slumber,

a little folding of the hands to rest—

and poverty will come on you like a thief

and scarcity like an armed man (Prov 24:33-34).

Certainly, the path of wisdom involves being active in what is purposeful and valuable in life, but in words equally stern as those used against the sluggard, the wisdom writers charge readers not to wear themselves out with over-work:

Better one handful with tranquillity

than two handfuls with toil

and chasing after the wind (Ecc 4:6).

Do not wear yourself out to get rich;

have the wisdom to show restraint (Prov 23:4).

Diligence is one thing, but a restless busy-ness is quite another, especially when it means we lack time or energy for others. But what is proper restraint?

|

It’s not just time, either. No matter how much we have, a scarcity mentality can easily come to dominate our attitude to money, too. It’s no secret that much of our personal sense of ‘enough’ is formed by our past experiences and our points of comparison, conscious and sub-conscious. While financial hardship is real, and many of us might be feeling the pinch a bit more lately, it’s fair to say that the majority of Australians have great wealth in both global and historical terms. In practice, ‘enough’ is a relative measure, and one with explicit spiritual implications for the wise:

Give me neither poverty nor riches,

but give me only my daily bread.

Otherwise, I may have too much and disown you

and say, ‘Who is the Lord?’

Or I may become poor and steal,

and so dishonour the name of my God (Prov 30:8-9).

The sage here, a man called Agur, argues that there is in fact such a thing as ‘too much’ even for our own good, let alone the good of others who could benefit from our surplus. Yet what is at first considered surplus can quickly become our new baseline, and then we don’t feel ourselves to be rich at all! Against this, Agur counsels us toward the spiritual discipline of simplicity: the cultivation of an attitude which puts front-and-centre our true (rather than imagined) needs and the true source of our blessing. There is much to be grateful for. We don’t have to have everything.

Tragically, the scarcity mindset actually brings about what it most fears: if we cannot do with less, we will inevitably seek out more. The more and more we need, the less and less there truly will be to go around. An attitude of simplicity does the exact opposite: it frees us to see and enjoy the plenty we already have. (For more on living with less, listen to MannaCast ep. 9).

Trap 2: “What’s mine is mine”

While the wisdom books are not anti-wealth, they repeatedly emphasise that money and possessions are only as good as what they can do: they are not an ends in themselves. Moreover, there is a consistent expectation that the rich will put their wealth at the service of the wider community. When Job reminisces on ‘the good old days’ in chapter 29, and acquits himself of blame in chapter 31, he does so with sustained reference to his obligations toward the needy:

If I have denied the desires of the poor

or let the eyes of the widow grow weary,if I have kept my bread to myself,

not sharing it with the fatherless—

but from my youth I reared them as a father would,

and from my birth I guided the widow—

if I have seen anyone perishing for lack of clothing,

or the needy without garments,

and their hearts did not bless me

for warming them with the fleece from my sheep,

if I have raised my hand against the fatherless,

knowing that I had influence in court,

then let my arm fall from the shoulder,

let it be broken off at the joint.

For I dreaded destruction from God,

and for fear of his splendour I could not do such things (Job 31:16-23).

Job does not view such acts as ‘above and beyond,’ worthy of special praise. Instead, awe of God means he could do little else:. Knowing God, keeping justice, and helping the needy are inseparable for Job: he does not stand on his private property rights or talk about how he earned it so it’s his. Maybe he was familiar with proverbs such as 14:31:

The one who oppresses the poor shows contempt for their Maker,

But whoever is kind to the needy honours God.

|

|

Image credit: http://breadsite.org. |

Perhaps counter-intuitively, a number of proverbs claim giving our money and possessions away is actually how we find wealth and blessing. Sometimes, this is simply because generosity is a good long term investment: strong relationships and a good name are worth more than gold. Other times, however, the scope of the resulting blessing is less clear:

A generous person will themselves be blessed,

For they share their food with the poor (22:9).

The blessing here is not defined as any material rewards we can expect, and likely has a wider view. After all, human life, from a wisdom perspective, is not a competition. Rather, reality, properly understood, is the kind of place where by sharing what we have with others we participate in true life. As Jesus himself is remembered as saying, ‘it is more blessed to give than to receive’ (Acts 20:35).

What this means is that if we hoard our time, or our money, or our stuff, thinking—falsely—that they are simply ours to do with as we please, we will not only be shirking our duty to others, but we will miss out on real, blessed life for ourselves. In the economy of God, the more life we give, the more life we find.

Trap 3: “The world is just a tool for us to use”

As C. S. Lewis noted in his prescient little book, The Abolition of Man:

There is something which unites magic and applied science while separating both from the wisdom of earlier ages. For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men…

We live in an age of unprecedented technical capacity. Undoubtedly, the scientific and industrial revolutions have borne many good fruits: penicillin, the cochlear implant, affordable production of basic necessities… But there is also a darker side. The increased (and increasing) mastery over the world and ourselves apparently rendered to us by technology has a tendency to inculcate a utilitarian, objectifying lens as our default way of seeing. From this perspective, anything and everything can be reduced to mere ‘matter’: the world becomes simply ‘stuff’ we can take apart, manipulate, and rearrange for our own ends.

|

|

| A proposed interior for Jacques de Vaucanson's famous "digesting duck" automaton unveiled in 1739. While Vaucanson's creation did not actually digest anything, he was hopeful such a device could be made one day. |

Tik Tok, the lesser-known machine man from L. Frank Baum's Oz series of books. Tik Tok was a clockwork device with operating instructions boasting: "Thinks, Speaks, Acts and Does Everything But Live." (Credit: Smithsonian Libraries.) |

When human beings are viewed as merely resources, this leads to the exploitation of the powerless by the powerful. When God’s creation is seen as ‘just stuff,’ the result is the despoliation of the non-human by the human. At its furthest extent, this view grants reality no superior claim over possibility: that is, if there is nothing ‘behind’ it all—no ordering mind, no purpose, no rights, no inherent integrity—then the state of things is merely contingent. What is can be otherwise, and we are in a position to make it so: like magic.

Some see the attempt to ‘subdue reality to the wishes of men’ as a distinctly Christian project, one bound up even with humanity’s vocation from Genesis 2 to have ‘dominion’ over the earth. But, as Jonathan has argued in MM May 2022, this is a profound misreading of the text. Moreover, according to the wisdom writers of the Bible, the cosmos is not humanity’s plaything. The primary ontological division is not between humanity—or me alone—and everything or everyone else, but between the creator and the created. Fish and trees and birds and rocks have their own value and their own relationship to their creator. ‘Nature’ is not just here to serve us: we are created beings with all the rest—we do not stand radically outside or apart from the non-human. We have a nature of our own, too: we have real obligations to God, each other, and the rest of creation, and we will ultimately be accountable to God for our lives, for we, along with everything else, are his:

Who has a claim against me that I must pay?

Everything under heaven belongs to me (Job 41:11).

In an age of seemingly limitless capacity, wisdom means accepting limits. We wield a power to shape and order the world which is unique among God’s creatures: it is a power God delights to grant us, but it comes with attendant responsibilities. He has made his world brimming with good things, but as we enjoy and pursue them we must always ‘stand in awe of God’ (Ecc 5:7).

%2C-detail.jpg) |

|

'Everything under heaven belongs to me.' God appears in the whirlwind: detail from an 1803-05 piece by William Blake. |

Fools for Christ

Wisdom will not solve all our problems; it does not guarantee us an easy life or that by it we will ‘get ahead,’ but that is not the goal. The goal of the biblical wisdom literature is to equip us to live life as we find it—to be clear-sighted: seeing reality in its right frame. While ‘the wisdom of this world’ (1 Cor 3:19) attempts to play life like a game—pursuing strategies to eke out maximum gain from our fleeting and uncertain span of years, anxiously seeking distraction and insulation from trouble—the truly wise accept trouble when it comes.

The greatest sage of all—the one who not only accurately comprehended but lovingly wrought the whole of reality—the God-man Jesus, lived a life at once full of joy, feasting, loving friendship, productive labour, gratitude, and peace, as well as deprivation, humiliation, pain, and grief. In doing so, he lived the truest human life there has ever been, dodging every snare, refusing to grasp after gain or covet control. He lived a life of contemptible foolishness in the eyes of the world, yet full of ‘the wisdom of God’ (1 Cor 1:18-25). Strange to say, it is in following after his pattern, in union with him, that we walk the paths of life.