Where is hope? It is hard to think of a more urgent question, both personally and politically. It is not just climate change and a global ecological crisis that is pressing on people (see the two articles on climate anxiety in this edition), but also an increasingly dangerous international climate, as well as the presence of seemingly unbridgeable chasms within our own society, rent by the culture wars.

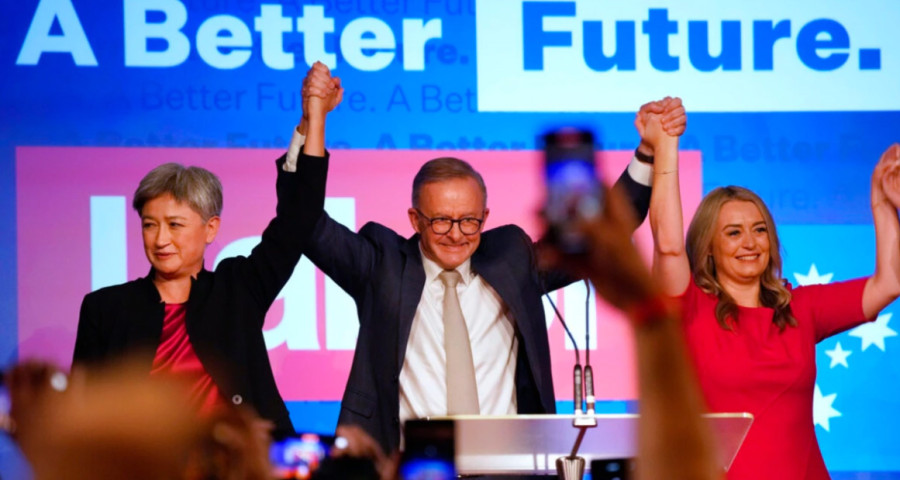

Four months ago, many Australians experienced a breath of new hope with the voting in of a new Federal Government in the May election. I have to admit to feeling a great relief at the departure of a government whose capacity for denial, cynical opportunism, self-aggrandizement and sheer irresponsibility had left me feeling numb. Moreover, the victory of Labor, but disciplined by the strong presence of the Greens and Independents, was a better outcome than I had hoped for, short of a hung parliament. However, politics has a way of pulling hopes down to the dust and the Labor Party has its own solid track record of cynicism and moral cowardice. While I am not embarrassed to admit that I feel more positive about the new government, I know better than to place my hope in it.

It is clear that so many of the issues confronting us—climate change, a broken housing system, rising poverty and hardship—require dramatic action by governments, and that requires substantial social and political pressure from below. Such action is dependent on hope, but so many people feel like the world is going to hell in a handbasket.

Through the ages, so many Christians who have moved earth and sky working for change have been inspired by the gospel vision of the kingdom of God. But what is the kingdom of God, and, more importantly, when is it? It is an idea that is subject to a number of sometimes contradictory confusions, but one well worth clarifying. The kingdom of God matters. It was central and essential to who Jesus was, what he was about and what he taught, and is foundational for how we look and work for hope in the world.

Jesus and the Kingdom Come

The kingdom of God is not just a teaching of Jesus; it is really the teaching of Jesus. For Matthew and Luke, the most succinct way they found to summarise what Jesus was doing was to say that he was ‘proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God’ (Mt 4:23, Lk 4:43). Likewise, when Jesus sends out disciples, the summary of his instructions is that they are to ‘proclaim the kingdom of God’ (Lk 9:2) or to pronounce that ‘the kingdom of God has come near’ (Lk 10:9). From the structure of the first three gospels, it is clear that everything Jesus did—whether teaching, healing, performing signs, receiving the lowly, or challenging the authorities—was either an instruction about, or an enactment of, the kingdom of God. As Jurgen Moltmann put it, Jesus is “simply the kingdom of God in person”.

There can be no doubt that for Jesus, the gospel writers and the early church, the language of the ‘kingdom of God’ held powerful political overtones. The Greek word we translate as ‘kingdom’—basileia—is the same word that was used to describe the kingdom of Herod. In the mouth of Jesus and in the ears of early believers and enemies, such language about God’s kingship was a direct challenge to the claimed authority of Caesar. And, just like the Roman Empire, Jesus’ teaching about the kingdom of God demanded obedience in this world. So already we can see, without having discussed any of the content, that the language of the kingdom of God brings us into direct tension with the established order, a fact which is amply borne out in the life of Jesus.

In both Matthew and Luke, the generalisation that Jesus was ‘proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God’ is soon followed by a (perhaps the) major set of gospel teaching: the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew (chs. 5-7) and the corresponding Sermon on the Plain in Luke (ch.6). It is clear that the writers have placed these teachings here to unpack for the reader in some detail what is meant by ‘the good news of the kingdom’. Immediately what these teachings make clear is that the kingdom of God requires a radical re-ordering of the relations between people. More importantly, it is not simply another political order in which people follow a different set of rules and conform to a new social structure; it is first and foremost an entirely different quality of how people relate to each other.

|

|

Christ of the Breadlines, 1951, by Fritz Eichenberg.

|

A very quick summary of the Sermon on the Mount illustrates the point. It begins with a definition of the ‘blessed’ state; that is, being in ‘the right place’, the place closest to God and to reality. According to Jesus, this ‘blessed’ state consists of being humbled and humiliated, feeling the pain of the world, foregoing personal gain, showing mercy, yearning for justice, being undivided in purpose, seeking peace, and suffering persecution. The purpose of those in this state (those in the kingdom of God) is to be of benefit to rest of the world (‘salt’ and ‘light’). From there, Jesus goes on to discuss, among other things, anger and hostility, sex and marriage, keeping your word, suffering oppression, refusing to retaliate, giving freely, love of enemies, prayer and fasting, debts, forgiveness, wealth and possessions, and judging others. If it is not already clear that this teaching requires a radical reappraisal of how we live in this world, Jesus drives the point home by stating that you cannot have two masters: you either follow the teaching of the kingdom or the system of empire. He then finishes the whole teaching by emphasising (twice) that those who are part of this thing are the ones who are doing it. Actions, not doctrines, are what count, but it is not just actions: the concern for outward conduct is matched by a concern for the interior disposition behind it. Giving money to the poor can either be an act of self-aggrandizement or of self-forgetful mercy: the kingdom of God claims the whole person.

Thus far, we can see that the kingdom of God has two essential components: (i) allegiance to God rather than any earthly authority (or system); and, flowing from this, (ii) the enactment of a whole new social order ‘in which grace and justice are linked’ (John Howard Yoder). Just as in the Old Testament, where Israel is called to be an alternative economic community that demonstrates the character of God (see Manna Matters Nov 2018), Jesus’ announcement of the kingdom of God points to the emergence of a new society in the shell of the old.

All of these things we see in the person and work of Jesus: sheer obedience to God and the breathtaking reconfiguration of relations between people. Where Jesus was, the kingdom had come.

The Coming Kingdom

It is not hard to see why the gospel message of the kingdom has provided a powerful inspiration for people through the ages to work for social and political change. But, too often, visions of the kingdom of God are identified with a set of (usually very laudable) social outcomes, such as greater social and economic equality, which are then associated with a series of policy measures that have been identified as the way to get there. Thus, the kingdom of God is something we build. It is something we look for in the near future. Indeed, the language of ‘building the kingdom of God’ is still very common today. There are a couple of problems with this.

Firstly, if the kingdom of God becomes an end that we pursue, then we inevitably begin to look for all sorts of means to get there. Sooner or later, the interests of some group will be sacrificed for the greater good, because the end justifies the means.

Alternatively, the other problem with pursuing the kingdom of God as a social vision for the near future is that it never comes. As I said, politics has a habit of pulling our highest hopes to the dust. How many great victories of social reform in history have soon soured into new squabbles and divisions?

So when is the kingdom of God? How do we work for it and how do we hope for it?

In the gospels, Jesus is clearly concerned to stress the nearness of the kingdom of God:

‘The kingdom of heaven has come near.’ (Matt 10:7);

‘the kingdom of God is among you’ (Lk 17:21).

This language echoes Moses’ summing up of the Torah in Deuteronomy, where he emphasises its attainability: ‘But the word is very near you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may observe it’ (Deut 30:14).

Nevertheless, it is also apparent in the gospel story that the full realisation of this kingdom is something that has not happened yet. Jesus repeatedly instructed his disciples to look forward to a coming day when justice will be done (see my article on ‘The Moral Ecology of Judgement’, Manna Matters Dec 2020). This is most poignantly put in Jesus’ last meal with the disciples: ‘I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer. For I tell you, I will not eat it again until it finds fulfilment in the kingdom of God.’ (Lk 22:15-16).

The New Testament presents us with the appalling paradox that we see the kingdom of God most clearly in Jesus’ death upon the cross. In human terms, this represents the failure of the social and political program of the Messiah Jesus. But what seems to be human defeat is discovered to be triumph in the resurrection. The huge significance of this is not simply that it proves Jesus was the Son of God, but that death and resurrection is the pathway of all hope. Jesus is the Second Adam, the first of many brothers and sisters, the first fruit of a new creation.

The New Testament is resoundingly clear. Hope is future hope, and it is the hope of a new creation: of justice done and all things redeemed, restored and fulfilled. However, this is not a call to resignation about the present, as if we don’t need to do anything because there will be pie in the sky when you die. The point of almost every New Testament passage that discusses future hope (what theologians so horribly call ‘eschatology’) is that the shape of this coming future is what instructs our action in the present. In Paul’s longest discussion of resurrection hope (1 Corinthians 15), he sums up the point of it all with this statement: ‘Therefore, my beloved, be steadfast, immovable, always excelling in the work of the Lord, because you know that in the Lord your labour is not in vain’ (1 Cor 15:58). As Lesslie Newbigin put it: ‘all the faithful labour of God’s servants which time seems to bury in the dust of failure, will be raised up, will be found there, transfigured, in the new Kingdom.’

The point of all this is more than just a motivational pep talk: it is profoundly ethical. Because we do not, indeed cannot, build the kingdom of God; because, like Jesus, we do not need to win in the human game of politics in order to be liberated to live according to the way of Jesus—which is the way of the kingdom—here and now. As John Howard Yoder put it, ‘The relationship between the obedience of God’s people and the triumph of God’s cause is not a relationship of cause and effect, but one of cross and resurrection.’

As the twenty-first century unfolds into a very uncertain future, we are going to need sources of hope that are more robust than a mere optimism that our best efforts will be effective, whatever that means. We will need a vision of the good that is strong enough and clear enough that we will live for it and work for it, whatever the world may be doing.

|

|

"The arc of the universe bends slowly, but it bends toward justice." Martin Luther King, Jr. |

It is because of such a robust hope that Christianity has been such a revolutionary transformative force throughout history - because followers of Jesus have not been perturbed to fight for ‘lost causes.’ And herein lies the great secret, the great dynamism of Christian hope: it is through the faithful (but never perfect) action of ordinary women and men that the future invades the present.

The Kingdom Among Us

This is generally presented as a mysterious paradox: a kingdom which is both here now, but not yet. However, I have now come to consider that the nature of the kingdom’s presence among us is not mysterious at all, but rather quite straightforward. The key lies in fully grasping the nature of what it means to make God king, and the simple formula lies at the foundation of the way that Jesus taught us to pray: ‘Your kingdom come, your will be done’ (Matt 6:10).

The reality of the kingdom of God among us is merely a matter of degrees. The extent of the kingdom’s presence is precisely the extent to which we have made God king (which includes the extent to which we are no longer bound by the dictates of ‘economic reality’), which is simply the extent to which we have enacted God’s will. The greater the extent to which we follow God’s will, and the greater the number of us who do so, then the greater the reality of the kingdom of God among us.

I am sure most people have had some experience when a body of people acted together in love, with one accord, and for a moment or a period opened up a space in which some sort of healing or restoration took place. Wherever the least are becoming first, the hungry are being filled, the broken are being healed and the tormented are being freed from their demons; wherever people are willing to stand against oppression and untruth, even to their own cost; there and then, God’s throne is coming to earth. Such are the moments of the kingdom of God among us. Its presence among us is ephemeral, waxing and waning with our own faithfulness and love. Of course, God is king whatever our attitude - what is in question is our participation in the kingdom that God gracefully holds open to us.

|

Pizza night at St. Matthew’s church in Long Gully, when people from all walks of life come together to share a meal, is a tiny glimpse of the kingdom.

|

Those moments when a collection of human wills are unified and moved by the love of God—those instances when we might be moved to say, ‘The kingdom of heaven has come near’—cannot be institutionalised. One of the great errors of the church in history has been, at various points, to identify itself as the kingdom of God. But the kingdom is a quality of faithfulness and not an entitlement; it is that for which we yearn and strive, not something we claim, much less something we can build.

But the one essential component of the kingdom of God is the one most likely to be forgotten: God. The kingdom of God takes place among us wherever human wills are being guided, not just by an idea or an ideology, but by the active, present living God whose full nature was revealed to us in Christ. Too often, Christians claiming to be working for the building-up of the kingdom use God and Jesus as figureheads, like Karl Marx the Father and Ché Guevara the Son. At its heart, the kingdom of God is not an objective outcome, but a presence. Just as Jesus was the living presence of the kingdom of God on earth two thousand years ago, so he remains now.