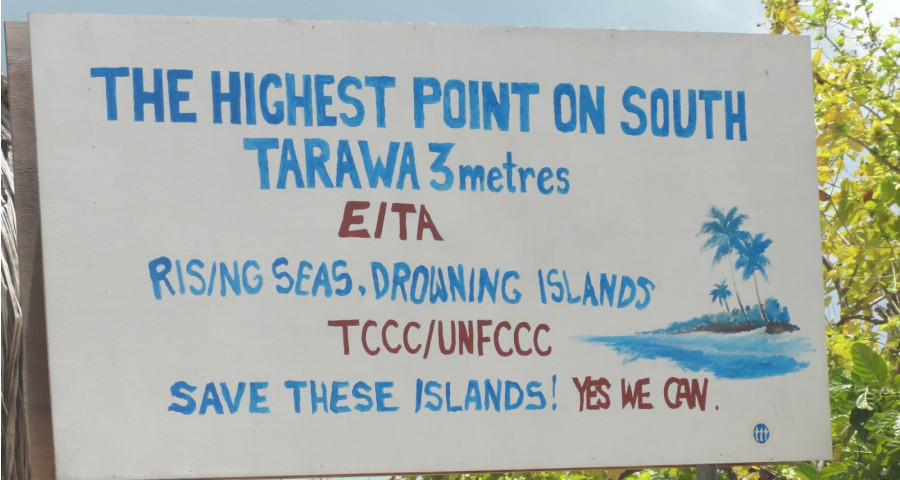

Above photo: Sign of the times in Kiribati. Photo credit: Erin Magee/DFAT

Imagine watching your home and the country you love be inundated by rising sea levels…

Imagine losing the place your ancestors are buried, and where you visit them...

Losing the land with which you have a deep spiritual connection.

Feeling your identity and culture threatened as you are forced to migrate to another country.

Or, being unable to face this, choosing to stay and sink with your home instead.

Can you imagine the anguish? The grief and pain? The anxiety as you watch this happening to the village next to yours, to other houses in your village and then finally to your own home?

This is the situation already faced by many people in the Pacific, and the threat on the horizon for millions more. I have friends who live on Kiribati, Tuvalu and parts of Fiji, and have talked to them about the awful impact climate change is having on them, physically and emotionally. No matter how much they pray, there’s simply nowhere more than two metres above sea level in Kiribati. And losing their land doesn’t just mean losing their homes, but possibly their culture, their whole way of life, as they are forced to move elsewhere. It’s an awful situation for them to be in, and they ask not just for our prayers, but for our action on climate, because every fraction of a degree matters when you’re living on the edge.

I’ve also heard Rev. James Bhagwan, General Secretary of the Pacific Conference of Churches, speak powerfully many times about the work they have been doing for years now: trying to work out how to provide pastoral care to those who have to migrate because of climate change, and also for those who will choose to stay and face the consequences. It makes me tear up every time. Tears of sadness, but also of frustration, because of our failure to respond quickly and adequately when the problem of climate change first came to prominence more than 30 years ago.

My brothers and sisters in Christ, who I am called by Christ to love and serve, are suffering like this because of rich countries like Australia who prioritise our coal and gas exports, our convenience and luxury, and our own wealth over the lives of these people and all future generations. To me, this lack of love for neighbour indicates that climate inaction is clearly not the way of Jesus.

The climate grief we see in the Pacific and elsewhere is just one part of a new (additional) global mental health crisis being created by people’s anxiety about climate change and their grief about the impacts they are experiencing. This crisis is particularly prevalent in young people, who are losing hope in their own futures.

.jpg) |

|

Nukufetau Atoll, one of the eight islands of Tuvalu.

|

A ground-breaking global survey released in September 2021 on climate anxiety in children and young people found that, of the 10,000 young people (16-25years) from 10 countries, surveyed:

- 56% said “humanity was doomed” due to climate change (including 50% of Australian respondents).

- 75% said the “future is frightening” because of climate change (76% of Australians).

- 83% said “people have failed to care for the planet” (81% of Australians).

- 55% believe they will have “less opportunity than their parents” because of climate change (57% of Australians).

- 52% said their “family security would be threatened” (48% of Australians).

- 39% said they were “hesitant to have children” (43% of Australians)

- When asked if governments are doing enough to avoid a climate catastrophe, 64% of young people surveyed said no.

- Further, a shocking 58% said that they feel governments are betraying them.

School Strike for Climate founder Greta Thunberg said in response to the study:

Young people all over the world are well aware that the people in power are failing us. Some people will use this as another desperate excuse not to talk about the climate – as if that was the real problem. In my experience, what’s making young people feel the worst is the opposite – namely the fact that we are ignoring the climate crisis and not talking about it.

We train our church leaders for pastoral care situations like funerals, generalised anxiety and illness, but we don’t train them in how to help their communities face their grief over climate change and the destruction of the planet, their anxiety about a climate-changed future and the ways in which climate change is (and will be) impacting on both their physical and mental health.

What many people don’t realise is that pastoral care for climate anxiety and grief can require a slightly different approach. Unlike generalised anxiety, climate anxiety–being concerned about your/your family’s future in the context of climate change—is a 100% rational response to the situation. It doesn’t mean you’re catastrophising, as is common with generalised anxiety, but rather that you are paying attention! The goal of climate pastoral care, therefore, is not to ease or remove the climate anxiety, but to find ways of living with it and taking action despite (or motivated by) that anxiety. It’s about stopping people from freezing and shutting down in the face of the challenge, but rising to it instead. By talking about and sharing our climate emotions and working together in a supportive church community to take action on climate change, we can both make a difference and have a chance of feeling better.

|

|

Photo credit: Lauri Myllyvirta.

|

My own journey with climate anxiety started in late 2018, when I was talking to a ministry friend about his doctoral research on emotional responses to climate change. That discussion evolved into our first Climate Pastoral Care Training Day. I invited psychologists working with climate psychology and climate emotions to come and share with ministers and church leaders.

One of our hopes was that the conference would invite a broader audience into the conversation around climate change. Instead of seeing the environment as a peripheral thing, or a low priority, we hoped that by showing how it links with pastoral care – something that is clearly central to every minister’s work – we might encourage people to come along who want to know how to provide the best pastoral care for their congregation. Then they might realise that climate change is more serious and relevant to the church than they thought. Instead of it being on a list of 500 priorities that they might get around to one day, they might think ‘we need to make this a bit more central to what we’re doing.’

It was an effort to get people along to that first conference because I constantly had to explain what climate anxiety was, and what climate pastoral care could be. But it was also kinda the perfect moment, as there were enough psychologists aware of climate anxiety, and enough research that had been done, that there was something to share and people to share it, but it was also still really cutting edge and new. It sparked something really wonderful as people realised we were talking about something many of them had experienced and had struggled with for many years on their own and without support. Now they had the opportunity to share with others who had similar experiences and to find comfort in that.

Then the Black Summer bushfires happened, and suddenly I didn’t have to explain to anyone what climate anxiety was anymore. I think the smoke blanketing Sydney, in particular, caused a seismic shift for people. As they and their kids struggled to breathe, as unborn babies were born premature and underweight due to the air pollution and the whole world suddenly seemed apocalyptic, dark and terrifying when you looked out the window, people began to understand how the abstract concept of climate change might translate into their lives, and it terrified them.

|

|

Bushfire haze hangs over Sydney. Photo credit: Nick-D.

|

Suddenly the demand for help with climate anxiety exploded, and our Climate Pastoral Care Conference in 2020 sold over 300 tickets. It was also driven online by COVID, so we had people tune in from states all over Australia, and even from overseas. In fact, I was contacted afterwards by people in the USA who wanted to start something similar. And now there’s even a movie about climate anxiety! (‘Don’t Look Up!’, 2021).

I’m continuing to work with colleagues and friends on some exciting new resources to help church leaders think through climate pastoral care and how they can help members of their community experiencing climate anxiety, grief and other climate mental health issues. If you’d like to know more, or assist, please get in contact via the email below.

To express interest in being informed about future exciting conferences and projects on the theme of Climate Pastoral Care, email Jessica at fiveleafecoawards (at) gmail.com.

****

If this article has raised strong emotions for you, please contact Lifeline 24/7 on 13 11 14, or connect with one of these mental health helplines: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/mental-health-helplines.

To connect with a climate aware psychologist or practitioner, please search Psychology for a Safe Climate’s directory or sign up for one of their fantastic workshops.