As I write, it is three weeks since the Australian nation voted not to recognise its First Peoples in the Constitution by establishing an Indigenous Voice to Parliament and to Executive Government.

There has been a plethora of opinion on the matter, both in the weeks leading up to the vote, and subsequently, as the nation has sought to come to terms with the result. When on Saturday 14 October every Australian on the electoral roll was confronted with that brutal binary—Yes or No—it is now apparent that our essential conservatism in relation to the Constitution kicked in and No became the favoured response. By and large, any doubt or uncertainty about the operation of the Voice was sufficient to prompt retreat to the safety of No.

For much of the nation, the matter is resolved and one’s attention can now turn to other matters—the cost of living, the challenges of climate, the geopolitical uncertainties, or just the day-to-day business of living. But for many Indigenous Australians, the referendum result is not so readily forgotten and the emotional impact of the rejection must still be processed and a way found to avoid a feeling of having been diminished as a people.

This article seeks to consider the referendum in retrospect by looking at the lives, words, and experience of two outstanding Aboriginal heroes from the past—William Cooper and Douglas Nicholls—Christian men who advocated for their people in times of immense marginalisation and oppression, and who stood against the overwhelming tide of settler discrimination. These men were champions of humanity, amongst the finest leaders of any race that this nation has produced, and we might usefully imagine what their counsel to their own people might be in these current circumstances.

But first we consider their lives. They were both from the same area of northern Victoria where the Murray River and the Goulburn River meet—William Cooper being born in 1860 in Echuca and Doug Nicholls in nearby Cummeragunja in 1906. Both were Yorta Yorta men, both embraced Christianity as young men, and both moved to Melbourne and became leaders who spoke out against injustice and outlined a Christian vision of a better, fairer society.

The much older Cooper mentored his young Yorta Yorta relative Nicholls, urging him to use the public profile he had acquired through his sporting achievements on the footy field and the running track to advocate for political change that would allow Aboriginal people to participate as equals in the life of the nation.

William Cooper

As a young man, William moved to join his family at the Maloga mission on the banks of the Murray where, in January 1884, he embraced Christianity following a church service, when he told the missionary, Daniel Matthews, that “I must give my heart to God”. He was taken under the wing of Matthews and his wife, Janet, who saw in him exceptional abilities. From Matthews he acquired a powerful conviction that black lives matter— that God’s love encompassed all people, and that God would provide salvation to the Yorta Yorta people just as he had to the Israelites, as set out in the Book of Exodus. These convictions were fundamental to the political activism Cooper would later undertake.

He was part of the relocation of most of the Maloga people to Cummeragunja in 1888 and thereafter used Cummeragunja as his base, travelling widely to find work wherever he could, spending much of his life working as a shearer, drover, horse-breaker and general rural labourer. It was not until he was in his early seventies that, denied entitlement to an age pension if he remained at Cummeragunja, he moved to Melbourne in 1933 and immediately began a remarkable political campaign.

Through all those early years, his thinking had been formed by his experience of constant poverty, by his observation of the decimation of his people, by the repressive policies of the NSW Board for the Protection of Aborigines (and similarly oppressive Victorian Government policies), and by his reading in the Scriptures of a God of love and justice. He had attended adult literacy classes, had read widely, and now set about writing letters, drafting petitions, and organising Aboriginal resistance. He maintained all these activities , despite constant disappointment and setbacks, until in November 1940 when he retired to Barmah, back on Yorta Yorta country, and died a few months later, in March 1941, age 80.

William Cooper’s life and work still inspire and motivate us today. Following another government refusal to listen to his pleas for his people, he lamented in 1937, echoing Matthew 7:9, that “We asked for bread. We scarcely seem likely to get a stone.” But his legacy is great. He is sometimes best remembered for leading a delegation to the German Consulate in Melbourne in 1938 to condemn the Jewish people’s loss, pain, and suffering at the hands of the Nazis—an action undertaken partly to draw attention to his own people’s loss, pain, and suffering. But his political activism went way beyond that, and his biographer, Bain Attwood, writes that ‘Cooper is remembered above all else for his prescient call for an Aboriginal voice to Parliament’.

In his successful advocacy for the establishment of a National Aborigines Day, Cooper made the following request of all churches:

We request that sermons be preached on this day dealing with the Aboriginal people and their need of the gospel and response to it … and we ask that special prayer be invoked for all missionary and other effort for the uplift of the dark people.

William Cooper was not only a hero of social justice—he was a hero of the faith. He might have been crushed by the disappointments and great sadnesses in his life, but he pressed on, as if seeing him who is invisible.

He had to bury his first wife, and then his second. His beloved first son, Daniel, named after Daniel Matthews, died in Belgium in the first World War, in the service of a nation by which he and his people were generally despised and rejected. He invested significant effort over several years in collecting 1814 signatures from Aboriginal people all over Australia for a petition to King George VI seeking Aboriginal representation in Federal Parliament, only to have the Commonwealth Government refuse to submit the petition to the King.

But in the face of these and other setbacks he persevered, and God made him fruitful in the land of his suffering (Genesis 41:52b). Not only did he inspire the next generation of Aboriginal activists through his nephew and protégé Douglas Nicholls, but his greatness is widely recognised, including by the Jewish community who, in 2018, organised a walk in remembrance of the man and his leading of the 1938 walk to the German Consulate in Melbourne.

Doug Nicholls

Douglas Nicholls was the grandson of William Cooper’s brother. William was 46 when Doug was born, and would, as a Yorta Yorta man of high degree, no doubt have mentored him to some extent over the years before moving to Melbourne in 1933. Doug had already been there for some five years, having relocated in order to play Australian Rules Football, at which he excelled. Doug had committed himself to following Christ one evening at the Northcote Church of Christ in 1932—so William Cooper arrived in Melbourne to find that his young relative was a celebrity for his football prowess and newly embarked on Christian pilgrimage. William sought now to enlist Douglas in the political struggle for Aboriginal justice.

And the young Nicholls did not resist, even if initially he was somewhat reluctant to use his sporting status as a platform to bring Aboriginal suffering to public attention. He played six seasons for Fitzroy in the VFL and was the first Aboriginal player to be selected for the Victorian interstate team—a spectacularly athletic 5ft 2inch wingman. He won both the Nyah and Warracknabeal Gifts as a sprinter and was a boxer in Jimmy Sharman’s Boxing Troupe. But he now joined his great-uncle in Aboriginal advocacy, both in the political bearpit, and later, following Cooper’s death and his own ordination, from the pulpit.

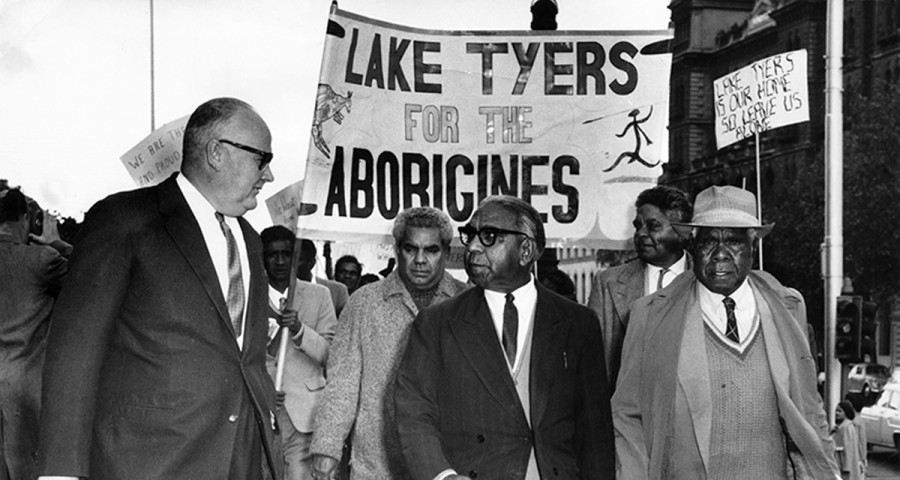

He became secretary of the Australian Aborigines League and was involved in lobbying members of the Federal Parliament for constitutional change that would give the Commonwealth responsibility for making laws for Aboriginal people, and this eventually led to the hugely successful 1967 referendum. In 1957 he formed the Victorian Aboriginal Advancement League, which continued to advocate on a range of fronts, including for the constitutional change, and he was at the forefront of the movement that became known as the “Yes” campaign.

He went on to do great community work and other public service, in partnership with his wife Gladys, and was eventually appointed Governor of South Australia, knighted by the Queen, and honoured with a State funeral following his death in 1988. A hero of his people and a hero of his faith, having lived an extraordinary life.

His biographer, Mavis Thorpe Clark, tells us that Pastor Doug believed that life was meaningless without faith, and that he would often speak in his sermons of Jesus being close to the earth, just as his ancestors had been. She quotes him:

Jesus himself was close to nature. Many of his parables are concerned with the earth, the mustard seed, the lilies of the field, the birds of the air. When he talked with God (he was) in the open field, on the mountain top, in the wilderness … Our people—our great people—were really close to God… We must hark back to our spirit strength—but now it is in Christ.

As we reflect on the dismal result of the 14 October 2023 referendum, we as a nation must ensure that we do not ever again render First Peoples inconsequential and invisible—the essence of dehumanisation. The zeitgeist that Cooper and Nicholls endured is not that which generally prevails in our times, and ways will be found to bring social repair through structures of active listening and empowerment. And I think those two great men would counsel their own people across the nation not to become embittered and calloused over by anger or hurt, but instead to hang onto hope in an imperfect world, and to work for a better accommodation with the dominant society, when bigotry will be swallowed up by love, and difference celebrated.

Chris Marshall has worked with Aboriginal people and their organisations for over five decades. It has been a vocation gifted by the Almighty, for which he is deeply grateful.