A Christian Ethic of Property (Part 1)

Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. ... There was not a needy person among them.

Acts 4:32-34

Australia is currently in the midst of a terrible housing crisis. As we all know, and as the media continually laments, the crisis is rooted in the stratospheric price of property. Yet whenever it looks like house prices might start falling, there is widespread alarm throughout the same media outlets. The Gordian Knot at the heart of Australia’s housing problem is the sacrosanct nature of rising property prices to a large (and disproportionately influential) segment of the electorate.

In the recent referendum, social media dis-information campaigns claimed that the Indigenous Voice to Parliament would result in a land-grab for people’s backyards. Despite the absurdity of the proposition, such claims got a disturbing amount of traction. History shows that, when people feel their property rights are threatened, politics becomes shrill and irrational. In Australia, this fear is perhaps sharpened by the subconscious recognition of (though unwillingness to admit) the fact that all freehold property is, by definition, founded on the arbitrary erasure of the ‘native title’ (to use the legal term) of the original inhabitants of this continent: that is, a massive act of theft.

What does all of this mean for how followers of Jesus think about and conduct ourselves toward property? On the one hand we are inheritors of a political tradition that gives a foundational place to property rights, but on the other hand we are haunted by the saying of Jesus that ‘None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions’ (Lk 14:33). In the first Christian community, shaped by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, we read that ‘no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but they held all things in common’ (Acts 4:32). Is this what all Christians should do? And, in a settler colony like Australia, what does justice for indigenous peoples mean for how we think about property rights?

In this article, I will begin the process of unpacking a Christian ethic of property. Here I will survey how the Bible discusses property rights, particularly noting the large transition between Old and New Testaments. The underlying claim is that, although these texts come from economic contexts which are radically different to our own, they nevertheless contain foundational dispositions to property, the importance of which continue to resonate down through time. In the article to follow this one, I will survey Christian attitudes to property over the last two thousand years, and especially the political ethic they derived from it. In the final article, I will attempt to draw these threads together to ask what it means for us here and now in twenty-first century Australia.

Property in the Old Testament

In the seventeenth century, commercially-minded Puritans often cited the Eighth Commandment—‘Thou shalt not steal’—as a divine institution of exclusive rights in property, thus allowing them to acquire, use, and dispose of property in whatever way they pleased (that is, whichever way was most profitable). They were right to identify the recognition of property rights in the Old Testament, but quite wrong in the character they attributed to such rights.

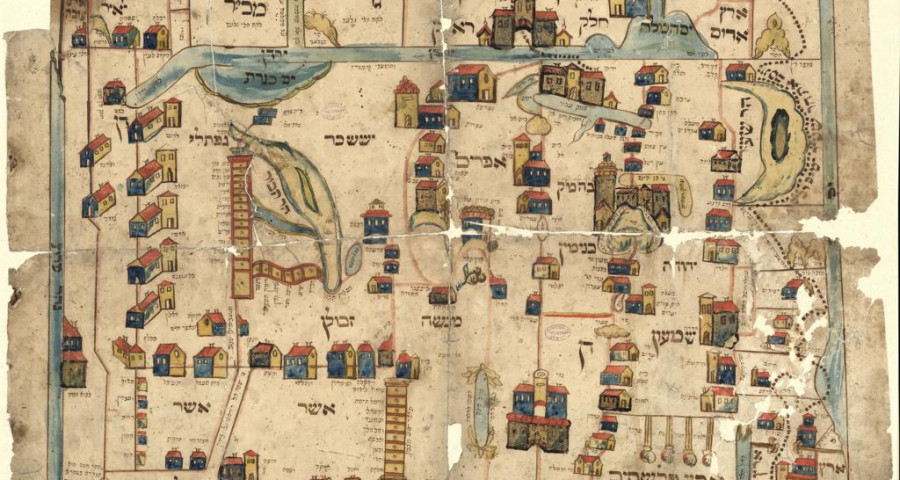

To catch the proper meaning of ‘property’ in the laws and commandments of the Old Testament, we need to see them against the luminous background of the divine vocation of Israel. As I have argued elsewhere (MM Nov 2018), Israel was called to be a people—a community, an economy, a nation—who communicated the character of God to the world through their redeemed relationships with each other, with the Earth, and with God. Central to this witness was its call to be an alternative economic community in which the land is kept bountiful, and there is enough for all.

It is towards this vision that the law codes of Israel instituted rights in property, but also placed limits on the rights of property. When we are talking about ‘property’ in the Old Testament, what is primarily in view are the things that were most valuable to an agricultural society: first and foremost, land; but also things such as livestock, millstones, and cloaks. The right of possession of such things is taken seriously: stolen property must be paid back double, and there is provision for accidental damage to property done by others. This all seems fairly normal, however, when we look a bit deeper, the Hebrew conception of property rights becomes much less familiar.

The foundational principle underpinning all of Israel’s property rights is the insistence that ‘The Earth is the Lord’s, and all that is in it’ (Ps 24:1). More particularly, ‘the Promised Land’ is that parcel of the Earth that belongs to Israel as a gift from God. In Deuteronomy 8 the Israelites are warned not to say to themselves that the land and its wealth is theirs because they deserve it, nor because they have earned it, and even less because they are entitled to it (the three central claims our culture continually tries to make about wealth and property), but to always remember that it is God’s sheer gift. In Leviticus 25, this notion is stated more forcefully: ‘the land is mine; with me you are but aliens and tenants’ (v.24). Israel’s tenancy and heritage in the land are secure, but—and it is a very big ‘but’—there are conditions placed on it.

The foundation of Israel’s architecture of property rights lies in one of the most tedious and skipped-over bits of the Bible: the allocation of land to all the clans in the twelve tribes of Israel (see Num 26 and 34; Josh 13-19). Unlike the Canaanite cities that surrounded them, where all land was owned by the king and/or an urban aristocracy, Israel was to have a broad distribution of property such that every family group had a stake in the land. Even more remarkably, the connection of families to land was to be inalienable: while families could make arrangements to lease their land to others, it could not be sold out from their possession. This is enshrined in the remarkable Jubilee laws of Leviticus 25 which instituted that every fiftieth year—after seven Sabbaths of Sabbath years—all land that had passed via commercial arrangements into the hands of others, had to return to its original heritors.

The purpose of the Jubilee laws was clear: in an agrarian society land is the basis of economic livelihood, and the foundational concern of Israel was that every family had a livelihood. In the words of Deuteronomy 15, ‘There shall be no poor among you’. There is much debate about to what extent, or if, these remarkable laws were actually followed in Israel, however, what is clear is that for the writers and compilers of the Bible, the Jubilee laws represent the pinnacle of the social and economic vision that God’s people were being called to. In this context, property rights are harnessed to a social vision; they do not float free from the social purpose they are meant to serve.

Rights in property were further attenuated in the Hebrew law by placing limits on what you could do with your property. The harvest laws in Leviticus 19:9-10 forbade harvesting a field of grain or olive grove right up to the edges, or going back to gather grain and olives that had been missed. Rather, these ‘gleanings’ were to be left for ‘the poor and the alien’ to gather. In effect, this law stipulates two principles that would be shocking to contemporary Australians: (i) you do not have a right to extract 100% productive efficiency from your own property, and; (ii) others in the community—in this case, the economically disenfranchised—also have some rights to your property. These principles are extended in the Jubilee Sabbath fallow laws: land can be under production for six years, but every seventh year it must be given a ‘complete rest’. Once again, the productive capacity of property is placed under limits for the sake of others who have a claim on it, in this case, the soil itself and even ‘the wild animals’ (see Lev 25:1-10).

.jpg)

Finally, Israel’s possession of (or, more accurately, tenancy in) the Promised Land was conditional on its following the Torah vision that it was given. Leviticus 26 gives a dire warning that failure to follow the Jubilee vision will result in disaster and dispossession for Israel. There is no divine entitlement to the land, only a promise linked to a practice of faithfulness, demonstrated by social and economic justice. (As I write this I am acutely conscious of the ongoing tragedy of Palestine and the modern state of Israel, a conflict that is rooted in a sense of divine entitlement that overrides any sense of justice.)

In summary, the Old Testament envisages property rights as having a key role in shaping its social vision. However, they are a particular kind of property right: the Old Testament does not recognise any form of absolute property rights, but rather places limits on the ways in which property can be used and the extent to which property can be accumulated.

The New Testament and property

To properly understand how property is discussed in the New Testament, we need to situate it against the backdrop discussed above, as well as see how this vision is being renewed, fulfilled and expanded in Christ. Also, we need to understand the New Testament teaching about property against the radically different socio-political context in which it is written: whereas the Old Testament envisages a legal-economic structure for an agrarian society overseen by a coherent political community, the New Testament is appealing to tiny, marginal communities (mostly urban) scattered around the Roman Empire.

Therefore, the New Testament does not offer any substantive teaching on property rights, as such. Rather, the general ethic of property espoused in the Old Testament is simply assumed by the writers of the New Testament. Of much more concern to the New Testament, and especially in the teachings of Jesus, is the attitude and practice of the Christian community in relation to property.

In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus famously initiates his ministry in Nazareth by reading a prophecy from Isaiah which finishes with a proclamation of the year of Jubilee (‘the year of the Lord’s favour’). He states that the prophecy has been fulfilled that day. Clearly, Jesus has no expectation of a major land restoration as envisaged in Leviticus 25: the social, economic, and political structures that would be necessary for that had long-since been erased. Rather, Jesus is taking up the theological and ethical meanings of Jubilee and breathing them into a radically new conception of the people of God in the world. In this new covenant, the role of the land in supplying both economic security and membership of the covenant community will be replaced by the community (koinonia) of those who are ‘in Christ’. This work of building this new community is central to Jesus’ ministry and the key to understanding what he has to say on property.

In the teachings of Jesus, the subject of property is subsumed within discussions of wealth and possessions. And there is just no way of getting around the fact that most of what Jesus has to say on wealth and possessions is about giving them up:

Sell your possessions and give alms. [...] For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also. (Lk 12:33-34)

None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions (Lk 14:33)

Sell all that you own and distribute the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me. […] How hard it is for those who have wealth to enter the kingdom of God! (Lk 18:22-24)

The teachings of Jesus are so challenging that they are mostly ignored within the church. To properly unpack all that is going in these texts would take more space than I have here, however, I will try to cut to the chase. Essentially, I think there are two key messages:

Jesus understands that possessions tend to possess us. The act of accumulating things over which we can say, ‘These are mine’, also amounts to an accumulation of spiritual transactions in which we have defined an element of our personhood against the rest of humanity. The statement, ‘These are mine’, by definition means, ‘They are no one else’s’. The larger the sphere of our lives that is defined this way, the larger our alienation from other people, and therefore, the larger our alienation from God. Behind this lies the suspicion that many of the practices by which property is accumulated involve mistreatment of people in some form or another. This explains the urgency behind Jesus’ calls for the renunciation of wealth and possessions: he sees them as concealing social injustice and risking spiritual death.

The converse of this is that distributing wealth and possessions (‘alms’ literally means ‘mercy’) is an act of social fellowship (koinonia) that is central to what Jesus means by ‘the kingdom of God’. Underpinning this is the insight that the strongest forms of human community are not those founded on voluntary friendships, but those of mutual material dependence.

The main concern of Jesus’ teaching regarding property is therefore not to establish the basis for, and extent of property rights, but rather to point us towards those dispositions and practices that transcend claims to rights and move us towards the loving relations that are the primary quality of the kingdom of God. This overall approach is maintained throughout the New Testament, but is perhaps most powerfully evident in Luke’s account of the Jerusalem Community after Pentecost.

A community of distribution

In Acts 2 we read about the dramatic events that give birth to that thing we now know as ‘the church’. At the beginning of this passage, the Holy Spirit is ‘distributed’ (this is the best translation of the Greek word diamerizo, often translated as ‘divided’ or ‘separated’) amongst the gathered believers and immediately releases communication that transcends barriers. At the end of the chapter we read about how this spirit-filled community began selling their possessions and distributing (diamerizo again) their goods ‘as anyone might have need’ (v.43). The story that recounts the birth of the church begins with a distribution of spirit and ends with a distribution of possessions. ‘All the believers were together and had everything in common.’ (v.44)

In Acts 4, this aspect of the Jerusalem community is revisited again with extra emphasis:

Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. With great power the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need. (v.32-35)

It is clear that the Jerusalem Community was an economic community, however it was not constituted by a new ordering of property rights. Rather, as Luke stresses, ‘no one claimed private ownership’. People still had the perfect right to retain private possession, they just didn’t care. This was not a product of a code of membership, but rather an instinctive response to living in the powerful presence of Christ’s resurrection and grace among them.

This point is made even more forcefully in the following story of Ananias and Sapphira (5:1-11), who lied to Peter about their contribution to the community. Peter makes clear to them, ‘While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, were not the proceeds at your disposal?’ There was no obligation for them to share. (The fatal consequences of their actions came instead because they lied in the presence of the Holy Spirit.)

Luke’s picture of the Jerusalem Community is a striking example of what economic anthropologist David Graeber calls ‘informal communism’. This has nothing to do with Marx or Lenin, but rather it is the term used to describe any social relationship that operates to the principle of, ‘from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs’. The primary instance of informal communism is the family unit: often those least able to contribute, young children, are the ones who receive most care. The informal communism of the Jerusalem community arose from internal motivation and not a codified set of economic arrangements. There is evidence from the New Testament and early church that lower-key versions of this sort of behaviour were widespread throughout the church.

As the Jerusalem Community grew in size and complexity, there was a felt need to put more structure around these economic sharing arrangements, and seven deacons were appointed to oversee things (see Acts 6). At this point, the church itself became a trustee of property for the sake of its members and of the poor, a position that it holds (in theory) to this day. But once again, these more organised forms of sharing did nothing to alter the conception of people’s underlying rights to property, but remained entirely dependent on voluntary participation. The primary characteristic of this economic community was not its structure of property rights, but the fact that members no longer claimed those rights. Over two thousand years of history, the strength of Christian economic community has waxed and waned precisely to the extent which this has continued to be the case, or not.

Conclusion

In this article, I hope I have demonstrated that the Old Testament provides a strong basis for recognising rights in property as a foundational human good, but it is a rather different kind of property right from what we are used to. In particular, the Old Testament repudiates any conception of absolute rights in property—the right to ‘To do with mine what I will’—and instead subordinates property rights to a broader social vision. The New Testament does nothing to alter this conception of property, but rather turns a laser-like focus on our attitudes and behaviours with regard to property, and the effects this has upon us and upon our neighbours. The early Christian communities continued to affirm property rights, but their defining move was ultimately to transcend them.

In the next article in this series, I will look at how this legacy has echoed down through the long history of the church, and how Christian thinkers continued to wrestle particularly with the political implications of property.