Does the subject of evangelism make you cringe? Do you associate it with awkward conversations or the sharing of religious clichés which you barely find credible yourself? For many Christians, the subject of evangelism is something that has been quietly dropped or explicitly disowned, and often for good reasons. There is little doubt that a certain sort of practice of evangelism has turned many off Christianity, both within and without the church. Those parts of the church that are most focused on evangelism have tended to have very little to say about many of the great challenges of our time, such as systemic economic injustice and the urgency of a multi-dimensional planetary ecological crisis. On the other side, those parts of the church that have been most focused on ‘social justice’ or ‘the environment’ have generally not had much to say about life beyond this activist quest. A common denominator between both groups is that they are primarily focused on speaking to themselves, giving little as to how to communicate across real human divisions.

This is a real problem. Both the evangelical version and the social justice version of Christianity are anaemic representations of the New Testament message, and neither is very well equipped to deal with the immense personal, existential, social, and political challenges of the 21st century. In this article, I want to lay out, in very simple terms, the case for the re-integration of Christian faith as a transformed experience of life (new life), a transformed practice of how we live in the and serve the world (economics, politics, ecology), and a dynamic message of good news that cries out to be shared, and that these things are not separate components of the Christian message. Rather, they are inextricably bound up together - each should lead to and require the other. To do this will require exploding some common understandings of ‘evangelism’ as well our understanding of what lies at the root of our social, political and ecological problems, and how we go about seeking change.

Evangelism as bad news

Our word ‘evangelism’ is drawn from the New Testament’s contention that the message about Jesus Christ is ‘good news’ (evangelion) for the world. Yet the experience of so many has been that neither the message shared nor the mode of sharing has seemed particularly good. The message often boils down to something like ‘pie-in-the-sky-when-you-die’, ‘get-out-of-hell-for-free’, or ‘Jesus-is-my-boyfriend/bestie/lifecoach’, or some combination of all three. Generally speaking, the supposed ‘good news’ has been a spiritual and private message whose implications are essentially internal and eternal.

|

|

There are some real problems with the underlying theology of the simplistic and two-dimensional message that is often presented in the name of evangelism, but that is a subject for another article. More importantly, in the presence of widely-felt existential threats - the gut-churning trauma of mental ill-health; the existential worry about dangerous climate change; and the experience of disintegrating social fabric - such a superficial and remote message feels like bad news. It feels like God, and those who would speak for God, do not really care about the deep travails of the world. Or perhaps more pointedly, it simply feels like an evasion of reality, which it is. In the harsh glare of post-modern relativism and hyper-individualism, the message and practices of what has been understood as evangelism just no longer seem credible to either hearers or would-be tellers. And so evangelism has been increasingly abandoned.

Another problem is that evangelism has often been understood as the proclamation of a message that floats free of the medium - the individuals and churches with which it is associated. However, Australians have historically had a pretty good radar for bullshit and hypocrisy (perhaps less so now), and the many public failures and shortcomings of churches have tended to render even their finest words hollow.

Finally, in Australia today we have been habituated to think about religious faith as a form of ‘personal values’: fine for me, but not something that can be ‘imposed’ on anyone else. And here, ‘imposed’ refers not to some form of legal mandate or cultural dominance, but merely articulating one’s faith publicly is seen as a form of ‘imposition’. We now have the spectacle of Christian parents choosing not to ‘impose’ their faith upon their children, neglecting to reflect that in almost every public space their children inhabit, whether real or virtual, they are constantly having the values of hyper-individualist relativism aggressively imposed upon them. If Christian faith is not actively shared then we do not leave our children, or anyone else, with a choice, for there is simply no choice to make.

The idea of Christian faith as a ‘personal value choice’ is utterly alien to the New Testament. The Christian message is about the predicament of all humanity (and, indeed, the cosmos), about what God, in Christ, has done for humanity (and the cosmos), and it is a message that, once someone has begun to glimpse the truth of it, transforms them into bearers of a message. We don’t come to the conclusion that climate change is a threat to life on the planet and then keep that conclusion to ourselves as a ‘personal value choice’. It is a subject that is inherently universal and public, and so too with Christianity. In fact, the case of climate change is really just one subset of ‘the problem’ that the Christian message addresses.

At the heart of the problem is the weakness of the modern Christian view of sin and salvation. ‘Sin’ is a word that has been isolated to a small sphere of personal moral behaviour and ‘salvation’ something made remote from the here and now. But what the Bible means by that big-little-word ‘sin’ is every single thing (every action, inclination, perspective, social force, etc.) that disconnects people from God, from each other, and from the created world. When the Bible teaches that Jesus came to save us from sin, it means that the work of Jesus is to restore us to the great communion of love between God, humanity, and creation, which is the only true habitat for life, the life that really is life. Until we see that the social, political, and ecological dissolution we see in the world has its source in every single one of us, and until we experience the message of Jesus as something that begins the reconciliation of all things with our own little life in tangible ways, then there is no message to share.

The world is beset by forces of ‘death’ on every side: spiritual, relational, social, economic, cultural, political, and ecological. ‘Who will save us from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord … For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has set us free from the law of sin and death’ (Rom 7:25, 8:2). But how do we communicate the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus to the world?

The good news of living differently

|

|

|

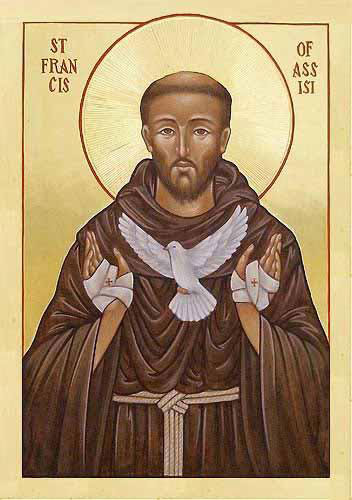

St. Francis of Assisi is often credited with advising: 'Preach the gospel at all times; and, if necessary, use words.' |

The Gospel of John opens with the stunning claim that God’s ultimate communication with humanity (the logos) has taken the form of a single human life in a specific time and place: ‘The Word became flesh’ (Jn 1:14). So often evangelical sharing has focused only on the death of Jesus, but the New Testament witness is that the good news of Jesus is the news about his whole life: the nature of his coming (in vulnerability and poverty); the content of his teaching (proclaiming the kingdom of God and his justice); the example of his life (mixing with the poor and outcast, bringing healing and liberation; challenging and exposing the ruling authorities); the form of his death (obedient to God and to love, refusing violence, killed unjustly by the authorities for speaking truth); the form of his victory over death (bodily resurrection); and the triumph of his ascent to heaven and the sending forth of his Spirit into the world.

This last, and often neglected, part of the story is the bridge between God’s Word becoming flesh in the life of Jesus, and the renewed enfleshment of God’s Word again and again and again in the lives of ordinary women and men through history, who corporately come to be described as the Body of Christ. Although words are always important and necessary, the witness of the Bible is clear: God’s primary mode of communicating with people is through the lives of other people.

For the last 13 years, Manna Gum has been attempting to make the case that Australian Christians need to rediscover the vocation of living differently to the norm of our affluent consumer lifestyle, and that we should be people who choose to live at a lower material standard of living from that to which most Australians aspire. There are a multiplicity of reasons for this: for the sake of the planet, for reasons of justice, for the health of our families and churches, and for the health of our own souls. Another key reason is so that we can once again be people who communicate Christ to the world.

In Australia today, words carry little weight, and religious words are viewed with more suspicion than most. We cannot communicate Christ by simply continuing to spout two-dimensional formulas in religious terminology that do not mean anything to anyone. What does communicate are lives lived against the grain, in the service of love. I am fully convinced that most evangelical thing Christians can do today is to live well in an age of bad living. And if this is true of individuals, it is so much more true of churches: the most potent evangelical tool through the ages has always been that of Christian communities whose mutual love and care is practically and visibly evident.

This does not mean that we can ever do away with words completely. Michael Frost writes that Christians need to live ‘question-provoking lives’; as the Apostle Peter advises, ‘Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect’ (1 Peter 3:15); and Paul writes, ‘Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone.’ (Col 4:6) But real communication about faith needs to be grounded in our own real-life encounter with Jesus, and it needs to reflect all the gritty and humble realities of that encounter. In short, speaking about faith needs to be more honest, less formulaic, and more real. The more our life is being transformed by Christ in an ongoing manner - that is, the more we are ‘working out our salvation’ - the more real content we have to communicate that is not reducible to simplistic formulas. But what gives words substance is the life that can be seen behind those words.

Evangelism, capitalism, climate change, and COVID

When Jesus travelled about ‘proclaiming the kingdom of God’, it had an electrifying effect amongst people and quickly drew the hostility of the ruling powers, eventually leading to his execution. The message that Jesus preached and the way he lived his life provided a clear challenge to the dominant world view and to the structures and vested interests of the status quo. In our language, Jesus’ message of salvation was inherently ‘political’. Sure, it was deeply personal, concerning the spiritual health of each person, but it was never private and it was never abstracted from the material and social out-workings of a person’s life.

|

|

|

‘The better the objects of agreement, the better the people’. St. Augustine of Hippo by Giuseppe Antonio Pianca, c. 1745. |

The more our faith in Christ is allowed to reshape the whole pattern of our presence in the world, from our home, work, and community life right through to our political outlook and activity, the more our sharing of ‘personal faith’ will be an inherently political act. If we are truly sharing about ‘the path that leads to life’ then it cannot help but shine a stark light upon the manifold forces of death we find in our culture: the idolatry of wealth and self; the ongoing destruction of creation; mindless hedonism; and our addiction to technology. The more fully we speak of the good news of Jesus, the more fully it will call into question capitalism, climate inaction, and the social and political divisions we have experienced during the COVID crisis.

Theologian Luke Bretherton has written that the art of politics (in the best sense of the word) is about the pursuit of common objects of love, whether that ‘love’ is focused on wealth and the protection of ‘my rights’, or upon seeing all humans and all nature flourish together. St Augustine wrote that ‘the better the objects of agreement, the better the people’. Currently, Australian politics is a mess because that which ‘we love’, speaking collectively of the nation, is not worthy of love. Evangelism is nothing if it is not the ongoing process of holding open the invitation into the great communion of love that God, in Christ, is working to restore us to (2 Cor 5:19). The more people who agree on this truly worthy object of love, the better our politics will become.

---

In conclusion, there is no other way of speaking of the core vocation of followers of Jesus but that it is the calling to be witnesses to the good news about him - to be people who speak of what they have seen and what they have experienced. Christians simply cannot put aside evangelism. But evangelism, properly conceived, is not the communication of some privatised, spiritually abstracted message couched in religious terminology that no one really understands any more. Here, in the most general terms, I have argued that our communication of the meaning and hope that is found in Christ (evangelism) is intimately connected to our own embodied ethics (our attempts to live gently, justly, and generously) and to our political outlook and political communication. The more our lives are shaped, transformed and saved by that deep and rich goodness that is found in Christ, the more natural and the more self-evident the sharing of such goodness will become.