A Christian Ethic of Property (Part 4)

In 2013, Kim and I purchased a vacant block of land (one third of an acre) in the Bendigo suburb of Long Gully, on which we eventually built a house. After twenty years of renting, we were taking our first steps towards what many see as the great Australian dream: home ownership. By great fortune, the block of land we purchased was the last in the built up area in our bit of Long Gully, and is immediately adjacent to bushland. The bushland abutting us is ‘unallocated crown land’ that has mining history dating back to the early years of the Bendigo gold rush in the 1850s, and so it will never be built upon.

We love having the bush right next to us, and our language (‘our bush’) betrays a sense of particular entitlement of enjoyment that is not recognised by the law. If you walk through the bush to the top of the hill, you can see across the valley of Derwent Gully Creek, showing a mix of bush, housing, and mining history.

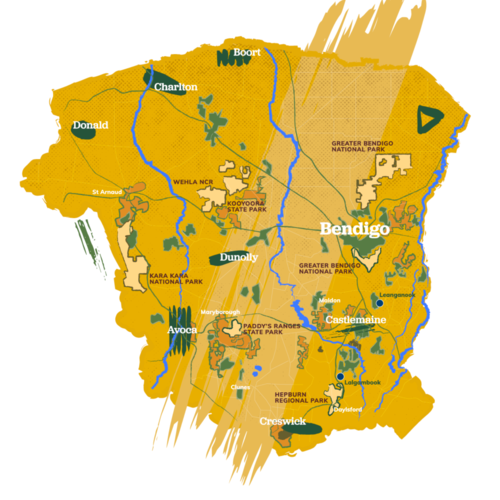

Looking out across this scene, it is not hard to picture things prior to the coming of Europeans: the surrounding hills forested by large and stately Iron Barks and, in the valley, a grassland or open woodland covered in Wallaby and Spear grasses, with a shallow, clear-water creek running for much of the year. This was the djandak (country) of the Dja Dja Wurrung, one of the Kulin language groups whose djaara (people) were distributed in clan groups from the Campaspe River in the east to the Avon River in the west, south from Daylesford up to Boort in the north (see the map further below).

In 1836, the first white faces appeared on their land: an exploration party of about 20 men, driving sheep and cattle, under the command of Major Thomas Mitchell, the Surveyor General of the New South Wales colony. Within a frighteningly small space of time the clans of the Dja Dja Wurrung were effectively dispossessed of their territory by a flood of sheep and men with guns. Without announcement, negotiation, or treaty, their land was simply taken. There was no compensation. Much of the violence that accompanied this process was due to the fact that, according to the complaints of the colonists, Aboriginal people refused to respect their property.

In the eastern states of the USA, there is a significant amount of land where modern title can be traced back to a direct sale from a Native American owner to an English colonist. In Australia, no such titles exist. All freehold title in Australia has been either granted by, or purchased from, the British Crown, who unilaterally took possession of all the land of this continent in 1788. Or at least it said it did, and it had the guns to answer anyone who said otherwise.

Property is theft

Over three articles in the previous editions of Manna Matters I have endeavoured to lay a foundation for a Christian ethic of property. I have been arguing that the biblical vision and Christian tradition offers a constructive vision of property that provides a radical yet constructive challenge to the dominant conceptions of our time. In the previous article (MM Aug 2024) I indicated I would conclude the series in this article with a proposal for a contemporary Christian practice of property. But that was foolish. I thought I could address the context of settler colonisation and our present context in one article, but the enormity of the facts of our history has overwhelmed me.

What does it mean to think about a Christ-centred practice of property in a nation that owes its very existence to a colossal act of theft? The third-of-an-acre which we bought in Long Gully was stolen land. In point of fact, the very form of property that it represents (a tradable freehold title) was created by theft.

In the previous article, I rejected the ideas of socialist anarchism which see all property as, by nature, a form of theft. The Christian tradition offers a much more constructive vision for the role of property. However, the understanding of property that the British brought to Australia in 1788 represents a turning away from that biblical vision. The result is that all modern forms of property in Australia were indeed created by an original act of theft.

But was it really stolen? Incredibly, this is a question that still remains obscured for many Australians. In a time of culture wars, claims about ‘colonisation’, ‘dispossession’, and ‘theft’ can seem to be merely part of the barrage of moral accusation that each side hurls at the other. Before we can reconstruct a positive and practical Christian ethic of property in Australia, we must confront this terrible question. I hope to do this, not through a series of moral assertions and accusations, but through an account of what actually happened. Somehow we need try and step back from the manic hand-wringing of both sides of the culture wars and come to a clear and sober account of our history and its implications for the present day.

Property before colonisation

Did Indigenous Australians own things? Did they own land? And what do we mean by ‘own’? Once again, this is a question that remains doggedly obscured for many Australians.

Rather than attempt to generalise for the whole continent, I will address the question through the specific and concrete example of the Dja Dja Wurrung, where I live.

The primary social unit of Dja Dja Wurrung (and broader Kulin) society was the ‘clan’: a localised group who were bonded by patrilineal descent (which was unusual amongst Indigenous Australians). There were sixteen clans (that we know of) who shared the Dja Dja Wurrung language/dialect. The names of most of these clan groups are still known, however, the name of the particular clan group that occupied the Bendigo region, where we live, appears lost to memory.

Each clan occupied a clearly defined area of land, to which they had a spiritual/cosmological connection, and over which they had particular rights and responsibilities. However, the rights of usage of particular resources within a territory (a river, a lake, a tree) were very complex, and could extend beyond the clan through kinship, marriage, and moiety relations. (Kulin peoples were divided into two moieties—bunjil (the eaglehawk) and waa (the crow)—that conferred certain religious and ecological responsibilities and determined who you could and could not marry.)

Nevertheless, despite the complexity of access and usage rights, there is no doubt that such rights were clearly, and even rigidly, defined, and the clan was the ultimate determiner and arbiter of such rights. In the terms of European international law (both then and now), the clan maintained ‘rightful possession’ of the territory and it exercised sovereign legal jurisdiction within that territory. Put simply, the clan was the owner of the land.

More than that, there is strong evidence that individuals or family groups within a clan could own a particular resource (for example, a tree in which wild honey was sourced, or possums could be smoked out) and it was considered a very grave offence to make use of someone else’s property. In the case of a possum tree, the ownership of the resource was tied to the significant amount of labour that had been put into developing the tree as a resource. This was a definition of ownership that the seventeenth century philosopher, John Locke, would have recognised (see MM Aug 2024). Moreover, just as in Britain, ownership of such property was inherited within the family.

Finally, there is simply no doubt that the products of Aboriginal craft—spears, necklaces, axes, nets, dili bags, coolamons, shields etc.—were considered personal possessions, and Aboriginal folk felt much the same way as Europeans about people pinching their stuff. Moreover, such items were traded in extensive exchange networks that criss-crossed the continent. The Dja Dja Wurrung were particularly keen to trade their cumbungi-shaft spears for the greenstone axes produced to the south. But land was never traded or taken. Due to the primary role of ancestral-spiritual connection to land (and the associated ecological knowledge that went with it), there was little logic to acquiring someone else’s land.

The erasure of ownership

Many Australians don’t realise how unusual the colonisation of Australia was, because we know that North America, the Caribbean, southern Africa, and many of the Pacific islands, were also subject to colonisation by the British. But how colonisation proceeded, and how it was justified, differed substantially, in ways that still matter today.

The Spanish and Portuguese empires in the Americas proceeded by ‘conquest’: a well established concept of international law where one political sovereign took over the sovereignty of another political unit by force of arms. They also claimed a right of ‘discovery’ of non-Christian lands that had been granted to them by the Pope, though no one else found this very convincing.

When the British first began establishing colonies in North America in the seventeenth century, there were some debates about what it was they were doing. By the eighteenth century, they had reached a verdict: they rejected the idea that they were engaged in conquest like the Spanish, which, in any case, still would not make them owners of the land, only the political rulers. Instead, British land acquisition in North America proceeded by purchase and by treaty. The reality on the ground was far more unjust and dubious than that, however the formal justification mattered, because it recognised both the political status and the rights of ownership of Native Americans. Similar processes were followed in New Zealand and much of the Pacific. [In between the publication of the print and online editions of this edition, a bill to re-interpret the Treaty of Waitangi was introduced to the New Zealand parliament. The explosive scenes that followed underline the importance of the treaty to the New Zealand experience of colonisaiton.]

Many Australians don’t realise how unusual the colonisation of Australia was.

However, when the British came to Australia, they colonised neither by right of conquest nor by right of purchase or treaty. They explicitly disavowed all of these usual practices. Rather, the British simply claimed that the continent belonged to no one (it was ‘desert and uncultivated’), and was thus free for the taking. Why so different?

There are two foundational elements to what has come to be known as the terra nullius argument (although that term generally wasn’t used at the time). Firstly, the British who came to Australia were shaped by Enlightenment ideas of a staged progression of human society from ‘the state of nature,’ through agricultural society, to urban and commercial society. Property rights were considered to originate with the development of agriculture. The absence of agriculture in Aboriginal societies meant that the British assumed an absence of property rights, especially in land. Bruce Pascoe has argued in Dark Emu that Aboriginal people did practise agriculture. I will not address the complexities of this claim here; what matters is that the early British colonists were convinced they did not. According to Watkin Tench, one of the most sympathetic and knowledgeable of the early colonists, ‘To the cultivation of the ground they are utter strangers.’

Moreover, the complexity of Indigenous property and access rights, described above, was largely invisible to the British. They simply lacked the mental furniture to comprehend them, even in the few cases when people were curious enough to inquire. The British were convinced that the people they found living in Terra Australis merely roamed over the face of the land. With their staged conception of human society, the British could tell themselves that they were bringing civilisation and advancement to the Indigenous peoples. As one colonist put it, advancing civilisation was ‘a progressive work’.

The second factor that led the British to claim Australia as terra nullius is more cynical. One reason that led North American colonists to prefer purchase and treaty over conquest was that they judged it a far easier and cheaper way to acquire land. The various indigenous nations of North America were daunting military opponents. Similarly, in New Zealand the British saw the Maori as formidable opponents. In contrast, following their first visit to Australia in 1770 (coming from New Zealand) James Cook and Joseph Banks reported to a government committee that they considered a settlement would receive little trouble from Indigenous inhabitants. This view was reinforced by their (erroneous) perception of how thinly populated the continent was. Moreover, Banks had concluded (correctly) that land could not be purchased from its inhabitants as they simply would not recognise such a transaction as possible.

On the other hand, as colonial courts were acutely aware, if the British acknowledged that they were conquering Australia, then, according to their own law, they would have to acknowledge the existence of a prior legal system, and thus the existence of prior rights in property. As one High Court judge later made clear (Coe vs Commonwealth, 1979): ‘It is fundamental to our legal system that the Australian colonies became British possessions by settlement and not by conquest.’

Thus, whereas Cook’s orders in 1770 had stipulated that he was not to seize any land that was inhabited, Arthur Phillip’s orders in 1778 were to simply take whatever land was necessary to establish the colony. Every increment of colonisation thereafter proceeded on the same understanding. As historian, Stuart Banner, puts it:

British lawyers and colonial officials concluded that Britons were no more bound to respect the property rights of Aborigines than they were to respect the property rights of kangaroos.

Doubts about terra nullius

Nevertheless, despite the weight of intellectual and institutional pressure advancing the idea of Australia as terra nullius, it was not long before people began to perceive the lie. Arthur Phillip himself quite quickly came to understand that the colony had unjustly appropriated the land of the Eora, and this was a key reason he was so keen to limit the geographic area of the penal settlement. He hoped that Port Jackson could remain an isolated British outpost, perched on the edge of a vast continent.

It was a vain hope. Once there, the pressure towards continual expansion was irresistible, and the primary driver of this was not official policy but settlers themselves. Again and again, settlers defied official decrees and pushed the bounds of colonisation further. This is testified by the strange fact that the closest thing to a colonial aristocracy in Australia were people known as ‘squatters:’ people who illegally occupy some else’s land.

But the further and harder they pushed, the more the lie of terra nullius became evident as Aboriginal peoples fought to protect their lands. In 1802, when the French explorer Nicholas Baudin visited New South Wales, he harangued Governor King about the wrongfulness of ‘seizing the land which they own and which has given them birth’. King himself urged his replacement, Governor Bligh, not to overreact to Aboriginal crop destruction, ‘as I have ever considered them the real Proprietors of the Soil.’

By the 1820s and 1830s such doubts had become widespread, voiced in newspapers in Australia and in Britain, by parliamentarians and officials in the Colonial Office. The doubts about terra nullius were sharpened by increasing unease about the violence of the colonial frontier. Here is part of a sermon (later published) given by the Baptist preacher, Rev John Saunders, in Sydney in 1838:

First, we have robbed him without any sanction, that I can find either in natural or revealed law; we descended as invaders upon his territory and took possession of the soil. It is not just to say that the natives had no notion of property, and therefore we could not rob them of that which they did not possess; for accurate information shews that each tribe had its distinct locality, and each superior person in the tribe a portion of this district. From these their hunting grounds, they have been individually and collectively dispossessed. […]

Thirdly, we have shed their blood. […] We have not been fighting with a natural enemy, but have been eradicating the possessors of the soil, and why, forsooth? because they were troublesome, because some few had resented the injuries they had received, and then how were they destroyed? by wholesale, in cold blood; let the Hawkesbury and Emu Plains tell their history, let Bathurst give in her account, and the Hunter render her tale, not to mention the South.

‘It is not just to say that the natives had no notion of property, and therefore we could not rob them of that which they did not possess.’

- Rev John Saunders, 1838

It was such an atmosphere that led to the only attempt in Australia to negotiate a treaty with Indigenous owners, between John Batman and Wurundjeri elders in 1835, in what was to become Melbourne. Although such purchases had been common practice in North America, it was immediately invalidated by Governor Bourke and the Colonial Office. Despite, the many voices being raised in objection both within and without government, once set in motion, the lie of terra nullius was considered too difficult to unravel. Indeed, it took 204 years following the arrival of the First Fleet for a court to recognise that the original inhabitants of this continent were in fact its owners.

Coming to terms with history

The High Court’s 1992 Mabo Decision is rightfully seen as a landmark moment in Australian history, and Eddie Mabo should be recognised not only as a great Indigenous leader, but as one the heroes in our nation’s history. However, amidst all the furore created by the Court’s simple recognition of the obvious fact of prior ownership, little attention was given to a more sombre fact that it also recognised: the majority of ‘native title’ on this continent has since been extinguished by the unilateral action of the British crown. The High Court, itself a product of this unilateral action, did not, and could not, challenge this fact.

There is simply no way to lay out a factual account of Australian history and avoid the conclusion that the British simply took land that belonged to others. In anyone’s ordinary moral language, this was an act of theft. (Indeed, the growing scholarly consensus is that even by the standards of international law in 1788, it must still be judged as theft.) Of course, the reason we have so long denied this very simple and obvious fact is that it places a terrible question mark over our very existence as a nation. It has a rather deflating effect on the ‘oi, oi, oi’s following a cry of ‘Aussie, Aussie, Aussie!’.

What is a Christian response to these facts? In the following article I will discuss some practical responses to property questions in contemporary Australia. Here, I want to address the more foundational question: do the facts of our history invalidate all modern property (i.e. all property derived from the British crown), and do they indeed invalidate our nation as a whole?

To some extent, we all know the answer to this question already: if we were to answer ‘yes’ to both of these questions, there would be virtually nothing we could do about it. In 2009, Anglican theologian, Peter Adam, suggested that, morally speaking, if Indigenous people asked all non-Indigenous people to now leave, then we should be prepared to do so: ‘I am not sure where we would go, but that would be our problem.’ I cannot agree. Relocating a nation of 28 million people is frankly impossible (who would accept this flood of emigrants?) and such a thought bubble advances us nowhere.

In my understanding, Christian morality aims to instruct our action within the actual conditions with which we are faced (see the series of articles on ‘moral ecology’ in 2020) and does not hold before us unattainable chimeras. We have no choice to but to accept that colonisation, with all its tragic wrongs, has happened, and cannot be undone. The social-economic system that supports 28 million people is woven from a tapestry of post-colonisation property rights—especially freehold and leases—that cannot now simply be erased.

Acknowledging that we cannot undo past wrongs does not mean that we cannot begin to act justly now.

But acknowledging this as our base reality is a very different thing from justifying what has happened, or claiming that there is nothing that can be done towards righting past wrongs. It seems to me that following Christ—the one whose work is to reconcile all things (2 Cor 5:19)—in 21st century Australia demands two things:

Firstly, we must tell the truth. We can do nothing else but acknowledge that Australia was created by a colossal act of theft from the First Nations of this continent, which was accompanied by many other appalling wrongs, not just in the act of dispossession, but a litany of injustices and indignities over two hundred years. Such an acknowledgement is not some woke act of self-flagellating virtue signalling (which, I admit, is becoming a problem) but simply a truthful statment of what has happened. It is the real world we inhabit and must face, and it is right to observe a time of lament.

Neither does such an acknowledgement invalidate everything about our history and heritage. There is much in Australia’s history and heritage that should be valued and celebrated. This also is the real world we inhabit. In holding these things together we reflect a biblical view of reality: human history, from the life of every individual to the life of every nation and society, is inflected with a tragic brokenness that replicates damage in the world; and yet the damage of our existence does not wipe out an ineffable created goodness that also remains. Australian history provides ample testimony to both the tragedy and the triumph of the human condition, and whenever we only acknowledge one of these strands, we misrepresent reality.

Secondly, acknowledging what has happened and how this manifests in the ongoing disadvantage and struggle of Australia’s Indigenous peoples, Christ’s people can do no other than seek to redress whatever wrongs can be redressed, and tend to the wounds that still linger. Acknowledging that we cannot undo past wrongs does not mean that we cannot begin to act justly now. We missed such an opportunity in last year’s failed referendum. But that disappointment does not diminish the work of healing and justice that lies before us.

It is beyond the scope of this article, and indeed beyond my competence, to lay out a full program of what such work looks like, suffice to stay that it spans a multitude of possible responses from the personal through to the political. However, in the next article I will (finally) try to bring all of this to a point in terms of a Christian practice of property in 21st century Australia. Such a practice must begin from where we actually find ourselves now, but also offer new ways of viewing property, and its role in our households, churches, and nation.