Churches are not very good at talking about politics. There are still many who think that faith and politics should not mix—that these two spheres of life can somehow be quarantined-off from each other, despite the fact that both deal with the fundamental questions of ‘how should we live?’ and ‘what is good for us?’. But as soon as we say something as basic as, ‘God loves justice’, then we are unavoidably in the territory of politics. (See our MannaCast series on Christianity and Politics for a fuller exploration of these ideas.)

For some time now, I have suspected that some Christians actually hold their political commitments more deeply than their theological commitments. For example, it is a very simple matter to show that, for biblical authors, the idea of a sovereign of God in no way conflicts with an understanding of human-induced climate change (see my article on ‘The Ecological Ethics of Genesis 1 & 2, MM May 2022). Yet the doctrine of the sovereignty of God is cited by many Christians (in Australia and the US) as a major objection to accepting the science of climate change. I suspect that for many, what is really at stake is not theology, but the (correctly) perceived threat to a high-consumption way of life. And the same can be true for many on the progressive side of politics: if political commitments to identity politics clash with biblical ideas on human identity, then it is faith that must give way.

When you combine these two factors—the fact that churches are not good at talking about politics, and that they often house people with deeply held political commitments—then it can make Christians unusually vulnerable to a stifling atmosphere of ‘group think’. In 2017, the year of the marriage equality plebiscite, I had the experience of being in both ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ churches (to put it crudely), where, in both, it was blithely assumed that I would share the stated position of that group. People didn’t bother to ask me, they just talked as if it was obvious that I would support the Yes campaign/No campaign. I was not particularly comfortable with either of those campaigns, but there was little space for that.

When you combine these two factors—the fact that churches are not good at talking about politics, and that they often house people with deeply held political commitments—then it can make Christians unusually vulnerable to a stifling atmosphere of ‘group think’.

As everyone knows, we live in highly polarised times. Political commitments now come in increasingly tightly-bound ‘package deals’: your views on climate change determine your views on abortion, trade unions, gender and sexuality, covid vaccines, and Israel/Palestine. If you tell me you are either pro or anti-abortion, I can guess, with reasonably high predictivity, your views on all those other issues.

This is madness. Every one of those issues represents its own universe of human tragedy and struggle, historical legacy, and social complexity. Each one of these ‘issues’ is, in fact, a tight complex of sub-issues which each deserve separate consideration. Each of these ‘issues’ changes complexion in different ways when you move from the realm ethics to politics, from the actions of individuals to the actions of governments. To subscribe to a pre-mix ‘position’ on any one of these issues just because you are on the conservative or progressive side of politics makes a travesty of the God who takes on flesh and enters into the suffering of the world.

I have argued elsewhere (see MannaCast ep. 33) that biblical faith does suggest some foundational political commitments for those who would follow Jesus:

- The rejection of all idolatries (ideologies?).

- The equality of all human beings.

- The human vocation to care for the earth.

- Humans are created for relationship and connection, and find their good in the good of the whole.

- The fundamental concern for just relations between people.

- The special concern for the poor, hurting, and vulnerable.

- The shaping of material/economic life to reflect each of the above commitments.

To my mind, these are non-negotiable Christian positions. Yet, just how these foundational commitments translate into the policies we might support on a given issue (much less, which parties we might support), is by no means straight forward. It depends, amongst other things, on the quality of our information and how well we understand what is actually happening in the world. Faith in Christ demands that we do politics, but that doesn’t make it simple.

***

Faith in Christ demands that we do politics, but that doesn’t make it simple.

I don’t propose to try and cut through all of this complexity here. It is my hope that over time, through a mix of articles and podcasts we can chip away at this enormous challenge, bit by bit. Ed Sheeran’s dad might have told him not to get involved in politics, religions, or other people’s quarrels, but here at Manna Gum, we are committed to doing just that.

For now, I would like to demonstrate that the bundle of political ideas that are ordinarily grouped together today under labels such as ‘progressive’ and ‘conservative’, are not the only ways, or even the most coherent ways, that political ideas may be assembled. To that end, let me explain why I am left-wing conservative radical, but not a progressive.

In the summer edition of Manna Matters this year, I outlined a mildly tongue-in-cheek Manna Gum Election Manifesto (“Vote 1 Manna Gum”). Many people would describe the collection of policies outlined there on climate change, taxation, and housing, as ‘progressive’. But not me. It is generally assumed that ‘Left’ and ‘Progressive’ mean the same thing, and likewise that ‘Right’ and ‘Conservative’ mean the same thing. I beg to differ. Here are the meanings that I attach to these terms:

Left-wing

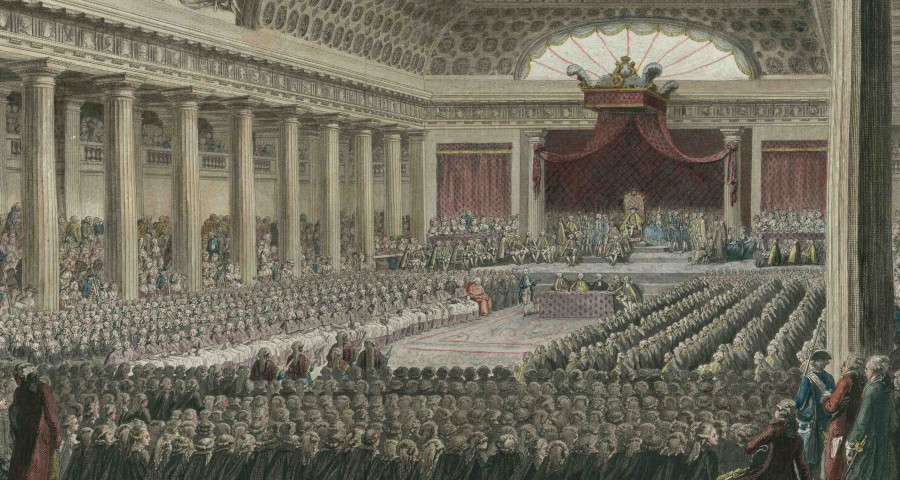

This term has its origins in the French Revolution, when, in the Estates General of 1789, the commoners sat to the left of the Chair and the nobility to the right. Since that time, left-wing politics has been associated with a huge array of different ideas, some inspiring and world-changing, some very dangerous and world-changing (think of the extremities of the French and Russian revolutions), and some very silly ideas that couldn’t change a wet nappy. Nevertheless, despite these cautions, the fact that left-wing politics is fundamentally concerned with the plight of the ordinary and forgotten people, and with reducing inequalities in economic and political power, means that, for me, it captures something very powerful in trying to translate the gospel proclaimed by Jesus into secular politics. By contrast, right-wing politics is always a rear-guard action seeking to protect the power and privilege of some group or other.

Keir Hardie (seated, right) was the inspirational founder of the British Labour Party. A coal miner and lay preacher, his left-wing politics was the expression of his deep personal faith and his own experience of injustice. Here he is with his close friend Andrew Fisher (standing, left), who emigrated to Australia and in 1908 became the first elected Labour leader in the world. The two first met as young men during the 1881 Ayrshire coal miners’ strike (Scotland).

Conservative

Modern conservatism (in the English-speaking world) also has its origins with the French Revolution, when the English parliamentarian, Edmund Burke, spoke out against revolutionary politics (as opposed to reformist politics) as endangering the social fabric. Genuine conservatism is concerned to protect the basic structures of nature and society on which we depend, and it is wary of how much change human communities can bare at any one time. That is, conservatism is (or should be) strongly rooted in respect for the created order. Much of what is labelled as conservatism today has very little interest in conserving things. J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were both true conservatives: their critique of the destruction of nature by the industrial economy was paralleled by their critique of its sundering of human community. However, their conservatism also gave them some large blind-spots about troubling elements of the social status quo, particularly the prevailing attitudes about race and empire. I am happy to be associated with the term ‘conservative’ when used as an adjective, qualifying the extremities of both left-wing and radical. But I am not happy to be associated with it as a noun: I am not ‘a conservative’ (more on this below).

Radical

The term ‘radical’ derives from the Latin, radix, for root. Radicals are not happy with superficial diagnoses of the human condition or band-aid measures for social evils. Radicals seek ‘root and branch’ reform. In the eighteenth century, radicals propounded crazy and unworkable ideas, such as the idea that every adult should get a vote. I contrast ‘radical’ (concerned with deep and durable change) with ‘extremist’ (concerned with sudden and violent change). Jesus was a radical exponent of the faith of Israel; the Zealots were extremists. Nevertheless, like left-wing politics, radicalism has also been associated with all sorts of silliness throughout history, hence my desire to qualify it with ‘conservative’. As William Temple, the great Archbishop of Canterbury during the Second World War, put it: ‘The conservative temperament tends to dwell on what is indispensable, that this may be safeguarded. The radical temperament tends to dwell most on the higher ends of life, that these may be facilitated. The world needs both.’

Not a progressive

In their truest sense, both conservatism and progressivism (where the ‘ism’ draws attention to an ideology) represent dispositions to history. Conservatism posits a golden era for society at some point in the past, and its politics seeks to reinstate elements of that age. Progressivism posits a golden era for humanity in the future. The past is always something to be left behind and abandoned for what comes next. The besetting sin of conservatism is to minimise the injustices of the social status quo. The besetting sin of progressivism is to denigrate anything associated with the old order. In my view, a Christian position must reject both these views of history. Rather, it sees every age as equidistant from eternity, none elevated above the others. Every age receives both the fundamental affirmation of God’s ‘yes’ and the challenging judgment of God’s ‘no’. The task of Christian politics is always to try and discern, and align with, God’s ‘yes’ and ‘no’ for the present moment.

***

The task of Christian politics is always to try and discern, and align with, God’s ‘yes’ and ‘no’ for the present moment.

Let me hasten to stress that I am in no way claiming that left-wing conservative radicalism is ‘the proper Christian political position’. It is merely the way that I am currently improvising the ongoing challenge of applying gospel insights to the messy world of politics. Moreover, the ways in which I unpack the terms used here, are not the only ways in which they can be used. Indeed, they are not even the only ways in which I use these terms. In this article, I have positively associated with left, conservative, and radical, but, at other times, I can also use each of these with a negative inference. Similarly, I have disassociated from progressive politics here; however, I also sometimes use the term ‘progressive’ with positive connotations. The one exception is the term ‘right-wing’, which, for me, is always negative.

If we are going to use terms like ‘progressive’ and ‘conservative’, ‘left’ and ‘right’, as more than mere badges of identity or as slurs and accusations, then paying attention to the heritage of political ideas and to the meaning of words can help us see beyond the strait-jacket of today’s package-deal politics. But ultimately, a politics that seeks to be faithful to Christ must move beyond such labels, and even beyond policy positions. More than anything, it must resist the absurdities created by ideological factionalism. Christian political thinking must be prepared to think about issues in their own terms and from a biblical framework, wrestling with the pain and complexity bound up in the human mess, and resisting the impulse towards simple and ideologically convenient resolutions. Ultimately, a Christian politics must acknowledge that any good that can be achieved through politics is only ever a limited and partial good—it is not an answer to anything. It is not through politics that the kingdom comes.