Want to make sustainable choices for clothing, but find yourself getting bamboozled by fibre content labelling? This guide will give you the basics.

Clothing in Australia must have a tag indicating the fibre content of the garment. The label may include a percentage for fibre blends (eg. cotton 85%/polyester 15%) or leave it up to your imagination (eg. wool/acrylic). If the exact percentages are left off, the fibres will still be listed with the largest percentage first.

The two overarching categories for fibres are natural and synthetic. Natural fibres are just what they sound like; synthetic fibres are a little trickier, since they have undergone a chemical change to turn their raw materials into yarns. They are generally made from either cellulose (usually wood) or petroleum (oil).

Natural fibres

Natural fibres all come from renewable resources and are biodegradable. As a category, they are the most eco-friendly choice for new clothing.

From plants: fibres made of cellulose

Cotton

|

|

Cotton is made from the seed fibre of the cotton plant. The overall sustainability of any given bale of cotton fibre depends greatly on how it was grown. Growing cotton uses a lot of water as well as large amounts of pesticides and insecticides which run off into the surrounding environment.

Organically grown cotton generally uses much less water, and no harmful pesticides or fertilisers. Additionally, organic certification by the GOTS also includes stringent criteria for the ethical treatment of workers, so you can be sure organic cotton has not been produced by child or forced labour, which is rampant within the cotton growing industry.

Bast fibres: linen and hemp

|

|

|

A flax field. |

Linen, hemp and ramie are bast fibres, which means they are sourced from the stem of the plant.

Linen comes from the flax plant. Flax can be grown on marginal land which is unsuitable for food production and absorbs a lot of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It requires much less water to grow than cotton does.

The hemp plant used for fibre is closely related to the hemp from which the psychoactive THC is derived, but contains almost no THC. There are many places where the growing of all hemp varieties is banned, which is a shame, since hemp is one of the most eco-friendly plants and fibres. It is one of the world’s fastest growing plants and does not require crop rotation. It needs very little in the way of water, pesticides or fertilisers. Hemp can be used to decontaminate soil and is excellent for carbon sequestration. Furthermore, a hemp crop produces around twice the fibre for the same area of farmland than cotton! The cultivation of low-THC hemp (aka industrial hemp) has been legal in Australia since 2017.

Ramie belongs to the nettle family. It is similar to flax and hemp, but the processes to extract the fibre are a little more labour-intensive.

From animals: fibres made of protein

Wool and animal hair

Wool is specifically a sheep’s hair, but many other animals are raised for their hair as well. Most of the fibres are named after the species or breed which grew them. Angora fibre comes from the angora rabbit, but just to confuse you the fibre from an angora goat is called mohair. Cashmere is the hair of cashmere goats, merino the wool of merino sheep. It’s easier to guess the animal that produces fibres such as alpaca, possum and yak.

The sustainability of wool is hotly debated. Sheep need to be well-managed so land is not overgrazed. They produce methane. Some are given insecticide baths. Forested land is cleared for grazing. Like cotton, the sustainability of any given bale of wool will vary, so look for more information on how it was produced. Merino wool is finer than that from most other breeds, but there is no difference in its farming.

For Australians, wool might seem like a local product, but sadly almost all our wool has to be shipped overseas to be spun or dyed before being returned to Australia, and this probably won’t be reflected on the label. There are few surviving Australian mills producing entirely local textiles, but hopefully there will be more in the future.

.jpg) |

|

Alpacas are considered by some to be the most sustainable fibre animal. Their soft lips and hooves mean less environmental degradation, and they require less water and food than sheep or cashmere goats, while producing larger and warmer fleeces. The colouring of alpacas ranges from black through brown and grey to white, meaning many colours can be made without dye.

Possum fibre is shorn from wild possums exterminated in New Zealand, where their introduction has caused a lot of harm to local ecosystems. No resources are put into growing the possums, and culling them is great for native species.

Silk

|

|

|

Bombyx mori, the silk moth. |

Silk is made by silkworms as they form cocoons in which to become moths. Each cocoon is one very long silk fibre which is then unreeled after boiling the cocoon to kill the developing moth inside (the pupae are a good source of protein and are eaten). The processing of silk uses quite a lot of water, and a lot of energy is needed to keep silkworm farms at optimal temperature.

‘Peace’ or Ahimsa silk is made by allowing the moth to survive and leave the cocoon before processing, but is not necessarily more eco-friendly than conventional silk. Tussah or wild silk is made from the cocoons of wild moths found in open forests and has quite a different texture, but is a more sustainable option.

Synthetic fibres

From petroleum: fibres made from polymers

Although subtly different, all the fibres in this category are made from oil and are plastics. They are made from a non-renewable resource and are not biodegradable. The microplastics polluting the earth’s rivers and oceans are mostly tiny fibres from these textiles, hundreds of thousands of which are sent down the drain every time you wash them.

Polyester

The most common fibre in the world! Over half the world’s garments are now made from polyester. Polyester is just very thin strands of PET plastic. Your clothes are almost certainly sewn with polyester thread, even if the tag says 100% cotton.

Acrylic*

Nylon (aka polyamide)*

Elastane (aka spandex/Lycra)*

*All various kinds of polymers, with a similar environmental impact to polyester.

|

|

Regenerated Cellulose: Rayon and all its friends

Viscose rayon

Rayon is a man-made fibre, but it is made from renewable materials and is biodegradable. It can be made from any cellulose, but wood pulp is the most common. However, the viscose process which turns it into fibre is extremely toxic, both for the factory workers and the surrounding waterways, where the chemical waste is often dumped. Land clearing for growing trees to make rayon is a huge contributor to global deforestation. Labels that say viscose, modal or just rayon refer to viscose rayon. Acetate is not exactly the same as rayon, but has the same ecological impact.

Bamboo

|

|

Bamboo means viscose rayon made from bamboo, which may be a more sustainable source of cellulose but the process is the same. Good PR has led many people to believing bamboo textiles are an eco-friendly choice, when in reality they fall very far down the list. Demand for bamboo rayon is leading to deforestation as land is cleared to grow it.

It is possible to instead process bamboo in a similar way to flax, which would make it a very sustainable fibre. Unfortunately, this is not common. Fibre processed this way will probably be labelled as ‘bamboo linen.’

Cupro and lyocell

Cupro and lyocell are also rayons, but more eco-friendly than viscose rayons. They are made in a similar way, but using chemicals which are much less toxic, and these are kept in a closed-loop system with no runoff into the environment. Tencel and SeaCell are two common brand name lyocells. Cellulose for Tencel is sourced from sustainably-managed eucalyptus forests, and for SeaCell from sustainably-harvested seaweed. Cupro is made from cotton waste.

A quick look at recycling textiles

|

|

| Recycled nylon is often made from old fishing nets. |

Natural fibres like cotton and wool can be recycled into new textiles, but they usually need to be mixed with new fibre to make successful yarns, so you will rarely see a 100% recycled cotton or wool garment. Old cotton can be used as a source of cellulose to make rayon.

Sometimes labelled as rPET, recycled polyester is not usually made from used polyester fibre but other waste such as plastic bottles. Recycled nylon is often made from old fishing nets. Recycled synthetic fibres have a lower environmental impact than new, but the problems of microplastic pollution and biodegradability remain.

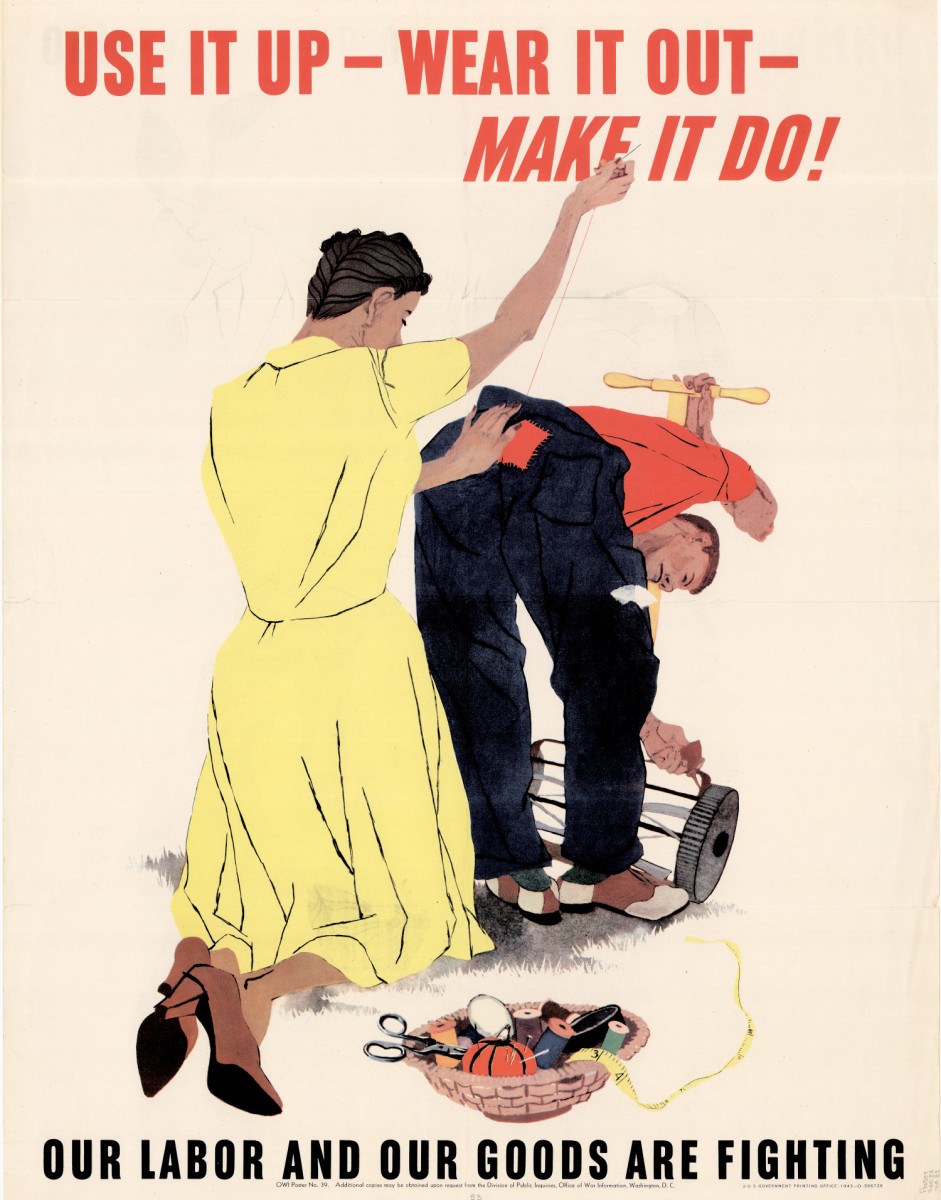

The biggest issue involved in recycling of any fibre is fibre blends. A poly/cotton t-shirt is either cotton contaminated by polyester or polyester contaminated by cotton. Recycling processes rely on pure materials, so blends are not recyclable! However, it should be noted that barely any of the world’s textiles are actually recycled. The most sustainable clothing choice by far is to keep wearing the clothing you already have, or to buy second-hand. Repair, rework, or rehome your old clothes if you can.

‘Hidden’ components

Parts of a garment present in small enough amounts don’t need to be on the tag. Don’t forget to consider the buttons, zips, Velcro, or elastic. All of these will almost certainly be synthetic polymers. Short of making your own clothes, there is almost no avoiding polyester thread.

Dyes and other treatments can also have huge sustainability implications. Textile dyeing is a water-intensive activity, and in many places runoff is a major cause of waterway pollution. Waterproof fabric coatings are almost always made of some type of plastic. Treating wool to be ‘superwash’ (machine washable) is another process with harmful chemical runoff problems, and it coats the fibres in polymer resin. Not only does this plastic coating destroy wool’s natural fire-resistance, it means it is no longer fully biodegradable!

Certifications you might encounter

Organic by GOTS

|

|

To be certified ‘organic’ by the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), a host of criteria which go well beyond farming conditions must be met. These include responsible land management and wastewater treatment, no use of environmentally hazardous substances such as pesticides, and fair working conditions. There are also restrictions on dyes which can be used. The textile must be 95% organic fibres to be labelled ‘organic’ and 70% for ‘made with organic materials.’

Standard 100 by OEKO-TEX

|

|

This certification by the International Association for Research and Testing in the Field of Textile and Leather Ecology (OEKO-TEX) means the product has been rigorously tested for harmful substances and is free of them. It does not have any specific environmental implications.

Made in Green by OEKO-TEX

|

|

Made in Green is a sustainability certification with wide-ranging criteria including the use of renewable energy, best-practice waste management, fair working conditions, supply chain traceability, harmful substance testing and product quality.

Woolmark by The Woolmark Company

|

|

Products with a Woolmark label conform to the quality standard set by Australian Wool Innovation Ltd, a non-profit organisation which does research and development along the supply chain for Australian wool. The standard focuses on quality and traceability rather than sustainability.

Better Cotton Initiative (BCI)

|

|

BCI is a non-profit governance group that promotes more sustainable and ethical cotton farming. It provides farmers with training on sustainable practices, but imposes no standard on the cotton they produce. It has been accused of allowing companies to ‘greenwash’ their products without effecting material change. BCI cotton is probably more eco-friendly than unlabelled cotton, but an organic certification is much better.

Some next steps

|

|

| War-time mending poster. |

Once you have your garment, it is your turn to contribute to its overall environmental impact. Whatever its origins, how you wash and wear it, mend and dispose of it will all affect how efficiently the resources embodied in its making have been used.

For more information on sustainable and ethical fashion, try Sustain Your Style, Shop Ethical!, The Ethical Fashion Guide, or Good On You.

The COVID-19 pandemic has sparked more interest in onshore processing for Australian wool. Add your voice to the National Farmers’ Federation and Victorian Agricultural Minister Jaclyn Symes in calling for government incentives to revive the industry. Support the few mills producing entirely local garments, such as the Great Ocean Road Woollen Mill.

Learn to sew or knit. Give yourself more control over how your clothes are made and reduce the distance your garments are shipped by eliminating at least one step. You will also be able to mend your clothes and reuse parts such as buttons and zips. The garment industry produces tonnes of waste from cutting out pieces, but it is easy for the home seamster to find uses for scraps, or you could learn to make ‘zero-waste’ clothes which use every part of a piece of fabric.

Tell your friends bamboo is rayon!

Phoebe Garrett is an inveterate maker of things, with a particular interest in textiles and adapting historical craft techniques to bring about a greener future. She has a degree in ancient history and is currently studying weaving.