The goddess Roma holding Victory regarding an altar with offerings.

The first Christians were atheists. Like the Jews and a number of other groups in the Roman world during the early centuries AD, Christians refused to be corrupted by or co-opted into the state religio: the traditional Roman system of worship and devotion which, during the empire, would increasingly absorb and blend with the religions of conquered peoples. The Romans tolerated much variety, and more as time went on. Polytheists themselves, they could in principle accommodate many gods and styles of worship under their rule. For the most part, they didn’t mind if you prayed to Ceres or to Cybele for a fruitful harvest, or whether instead of Ceres you called her Demeter. In all of these cases, you were still practising proper religio: acceptable Roman worship, which by the time of Christianity included veneration of the emperor himself.

In this context, Christians were atheists. They refused to sacrifice to or even acknowledge other gods, and they would not pay religious honours to the emperor. Such actions set them against the gods and the established order: against the gods, a-theists. What’s more, in the minds of many, this non-conformity threatened the pax deorum: the peace maintained with the gods by means of proper worship. Thus when plague struck or war raged these disasters were often seen as the direct result of divine displeasure brought about by people like the Christians for their stubborn refusal to participate fully in the system. This non-participation also undermined Roman efforts at social control and constituted a potential political threat, as Christian fellowship assemblies violated laws against unauthorised gatherings (where it was feared anti-imperial sentiments could take root and grow into rebellion). Far from a respectable religion then, Christianity was seen as a dangerous and contaminating superstitio to be discouraged or even violently stamped out for the sake of the common good of state and society.

Christianity as economic subversion

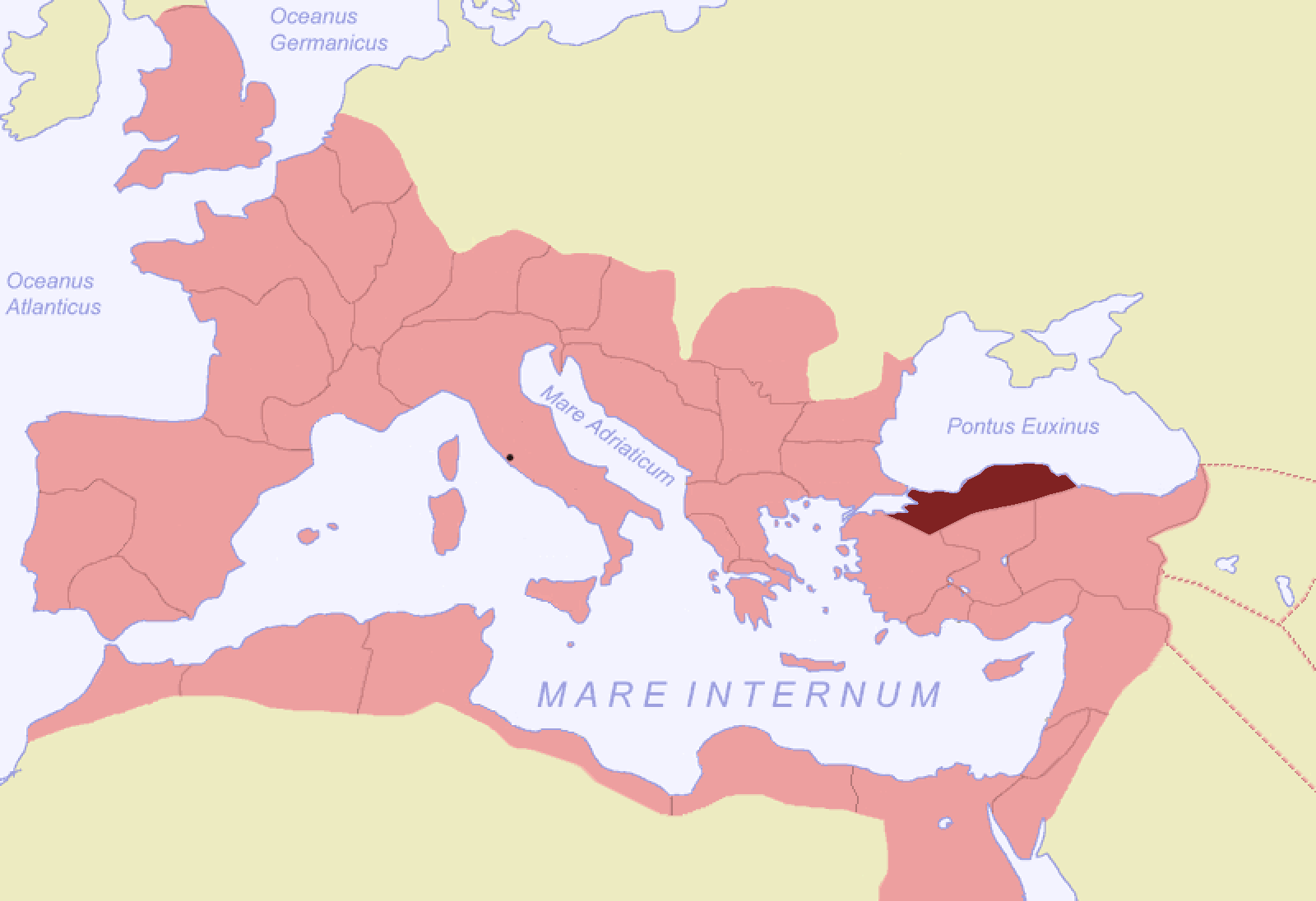

This is what Pliny, the Roman governor of Bithynia and Pontus (northern Turkey today), is trying to do when he writes to the Emperor Trajan personally some time during 111-113 AD to discover what should be done with Christians once he has arrested them. Pliny’sletter and Trajan’s response give us unique insight into the attitudes of the Roman authorities to this new faith and in what ways they saw it as harmful and dangerous. Though short, the exchange is very revealing. First of all, Pliny is anxious to get Trajan’s advice ‘especially because of the number involved’ in the accusations, and because ‘many persons’ across ‘every age, every rank [in society], and also of both sexes’ were implicated. The New Testament does not say how Christian faith reached Bithynia and Pontus (though 1 Pet addresses Christians there), but clearly it had spread quite rapidly and gained traction across social divides.

|

|

|

The Roman world under Trajan; Pliny's province of Bithynia and Pontus is highlighted (dark). |

The correspondence between Pliny the Younger (left) and the Emperor Trajan (right) is famous. |

Even though Pliny likely exaggerates when he tells the emperor that, because of the number of Christians, the temples ‘had almost been deserted’ prior to his crackdown, he is certainly concerned by their impact. Trajan’s relatively light response—that Pliny should not seek arrests, and only prosecute those who won’t recant under duress—also suggests Christians may have made up a significant minority of the population. Even more interesting is how Pliny relates the way the presence of Christians in the community changed the economic landscape. He tells Trajan that, until his arrests, ‘very few purchasers could be found’ for goods related to animal sacrifice: the market demand for such things was shrinking to such an extent that some historians say farmers in the region might have come under significant financial stress. A similar economic conflict is narrated in Acts 19 when craftsmen of pagan idols identify the spread of Christian faith as a risk to their livelihoods: Demetrius and his fellow workers realise that change in what people worship will change how they spend their money. From the very first then, Christian faith has had economic implications and presented a threat to certain forms of trade and business.

Yet many early Christians were at pains to communicate that they were not members of some anarchic ‘depraved, excessive superstition’ of the sort they were often accused: they may not have prayed to the emperor, but they prayed for him regularly. What’s more, far from constituting a breeding ground for rebellion or promoting criminal or immoral behaviour, Pliny says he learned from some ex-Christians exactly what was ‘the sum and substance of their fault’, namely that they met together to sing to Christ and ‘to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not to falsify their trust nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon’. Later the same day, they would meet again to eat together: nothing weird, he adds, just ‘ordinary and innocent food’.

Hardly the stuff of deranged revolutionaries or dangerous fanatics. The early Christian writer Tertullian underscores this point when he entreats his adversaries, saying:

we are human beings and live alongside you—men with the same ways, the same dress and furniture, the same necessities of life… we live with you—in this world.

Except the Christians were a threat: perhaps not to people, but to the kind of social, political, religious, and economic order under which everyone in the empire lived. Indeed, the Christians quickly gained a reputation for refusing to buy into the Roman system: they were conspicuously absent from public shows, processions, banquets, and ‘games’ (races and gladiatorial spectacles), and they obstinately refused to sacrifice to the right gods and worship the emperor; things it was thought were essential to secure the prosperity of the empire.

Pliny’s question to Trajan in the opening of the letter centres on this issue: he asks him to clarify exactly what it is about Christianity that is punishable. Is it the commitment of various offences that are associated with Christianity (common rumours at the time included incest and cannibalism), or is it ‘the name itself’—simply being a Christian—that merits execution? Bible scholar and theologian Graham Cole has noted that the name ‘Christian’ identifies one’s prime allegiance as being to Christ. Thus to hold to the name is to hold to Jesus Christ first, even where this conflicts with other loyalties and compulsions. The early Christians saw all kinds of conflicts between the way of Christ and the way of the world around them, and they chose to opt out of these in potentially destabilising ways. The Emperor Trajan’s response is terse, but seems to affirm that bearing the name alone, if unrepentant, is worthy of death: no higher king and no rival kingdom can be tolerated.

The Empire of this World

|

|

|

The Emperor Trajan depicted in the Egyptian style making offerings to the Egyptian gods. Dendera Temple complex, Egypt. |

Matt Anslow’s recent series of articles on the book of Revelation helps us begin to navigate what is different and what is not between the situation of the early church and the church in the wealthy west today. Each article asks the question of how we might live lives that say, in the words of one martyr in 180 AD, ‘the empire of this world I do not recognise.’

The reality is it is all too easy to become comfortable within the reigning system: to lose sight of the fact that allegiance to Christ necessarily makes people ‘aliens and strangers in the world’ (1 Pet 2:11). Yet the apostle Peter’s exhortation to the congregations of Turkey is not:

live such similar lives to the pagans that they may see you are no different to them and therefore present no issue (and no appeal),

but rather

live such good lives among the pagans that, though they accuse you of doing wrong, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day he visits us (1 Pet 2:12).

Peter does not advocate a compromise with the world and the Roman system, but lives of winsome integrity within that system. As one preacher friend of mine put it: Christians are called to fit in where they can, but to stand out where they must.

Stand out where they must. Often this calling is readily applied to our own personal and moral lives of faith: we must not worship the false idols of sex, money, power, fame, etc. and we ought to be careful not to turn our successful career, or children, or partner (or our desire for these things) into our own little god. This is certainly true, but the first Christians didn’t stop there. We still live in the empire of this world. It may have changed its shape, but it has not changed its nature. We still ought to pray for it and seek its benefit, but we do not play by its rules. Christian faith, therefore, remains inherently destabilising not only to our inner life and personal gods, but to the world at large: to our collective social, cultural, and political idols too.

Roman relief depicting the sacrifice of a bull (plaster copy).

Few today make sacrifices to secure peace with the Roman pantheon, but our culture still tells its own stories of how to gain and maintain prosperity. What are the unquestionable meta-narratives of our world today? What do we put our faith in? What are we obliged to serve, and at what cost? Brian Rosner, principal of Ridley College in Melbourne, offers one compelling candidate:

The economy has achieved what might be described as a sacred status. Like God, the economy is capable of supplying our needs without limit. Also, like God, the economy is mysterious, dangerous and intransigent, despite the best managerial efforts of its associated clergy.

To take just one element, the imperative towards growth in our capitalist economic system is unchallenged by any of the three major political parties in Australia. Yet the constant drive for more necessitated by the growth model is the engine of ecological overreach beyond the limits of Earth’s resources and leaves little for those who need it most. Is it true there is no alternative? What are the risks of non-conformity?

Controversially, the co-founder of permaculture, Dave Holmgren, has theorised how the actions of relatively few in a growth society might threaten to destabilise the larger system. To oversimplify, he argues that if only 10% of the population (in, say, Australia) were to consume 50% less, this would constitute a 5% reduction in overall demand, presenting a significant problem (maybe even a crash) for any system reliant on a constant increase in material consumption. Everyone, including Holmgren, can agree that the prospect of a spontaneous economic collapse is undesirable, but he argues that in the long term perpetuating the current system might be even worse. Planned transition is no doubt preferable, but seems unlikely without being prompted by a demonstration of both need and desire. How might Christians seek to live lives of godly disruption here and now?

In the eyes of the prevailing paradigm, though, non-conformity with the system will often be seen as more foolish than sacrilegious: Pliny can’t understand why the Christians remained obstinate even when given multiple chances to recant, with no further punishment if they did. Historian Everett Ferguson relates how it would have seemed such a little thing, to the Roman mind, ‘to burn a pinch of incense on an altar or swear by the emperor, but this was something that committed Christians would not do.’ Instead, this apparently little thing was something they were willing to die for. It made no sense to so many bewildered Roman officials across the empire who repeatedly put Christians to death.

Fortunately, Christians in Australia are not currently at risk of execution, but we must be careful not to let this blunt the edge of our witness. Mortal danger tends to throw the question of who and what we live for into stark relief, but normal life is made of normal choices. ‘Little’ things like where and how we invest our money and how we live with our material goods point to the world we long for and to the God who calls us there.