Jesus casting out the money changers from the Temple by Giotto, 14th century.

So much of what we take for granted in contemporary life, from pens to penicillin, iPhones to eyeliners, comes from the accumulation and mobilisation of capital. Whether governments, individuals, families, communities, or corporations take the lead, the ability to marshal financial resources to facilitate the production of goods and services profoundly shapes our lifestyles and opportunities.

Of course, there is no economy without ecology, and our collective drive to accumulate more and more has had a profound impact on Creation. We are burning the furniture to heat the house. It is not at all clear that humankind will make the necessary adjustments to slow and reverse the accelerating climate crisis in time to avoid catastrophic change, but if we do, changing patterns of investment and consumption will be fundamental drivers of that success.

There are many people doing inspirational work to mobilise for change, including some working from inside capital markets, and in the realm of government finance, that we will return to below. But first, we need to remind ourselves of the dangers that lurk in this conversation.

We can’t forget that Jesus had a lot to say about money, investment and capital formation (ripping down old barns to build bigger ones), and it was all pretty ominous. Influential Franciscan theologian Fr Richard Rohr has just completed a series on money in his September 2021 daily devotions for the Centre for Action and Contemplation. The key thought that lingers for weeks after reading the series is that money makes us sick – it causes disease of the spirit and the eyes.

In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus personifies money as the god Mammon, who calls us to worship. ‘Mammon becomes then a source of disorder’, Rohr says, ‘because people allow it to make a claim on them that only God can make. “Mammon illness” takes over when we think all of life is counting, weighing, measuring, and deserving.’

|

|

|

Sketch of John Woolman. |

In terms of its power to blind, Sallie McFague’s reflection introduces John Woolman, an 18th Century American Quaker. Woolman, she writes:

had a successful retail business and gave it up because he felt it kept him from clearly seeing something that disturbed him: slavery. He came to see how money stood in the way of clear perception of injustice: people who had a lot of property and land needed slaves to maintain them (or so these folks reasoned). He saw the same problem with his own reasoning… whenever he looked at an injustice in the world he always saw it through his own eye, his own situation and benefit… Once he reduced his own level of prosperity, he could see the clear links between riches and oppression. He wrote: 'Every degree of luxury has some connection with evil.'

Jesus’ warnings about wealth in the Sermon on the Mount take what appears to be a detour into ophthalmology to make that very point (Matt 6:22-23). Money distorts our perceptions and clouds our judgements: it gives us unhealthy eyes with which to see the world.

So before we look at the power of investment and capital formation to contribute to the creation of a better world, we need to touch on ways to make sure our eyes are as healthy as they can be. We need to recognise the symptoms of Mammon disease, and know the remedies.

Breaking the power

You can only really do three things with money: spend it, save it, or give it away. We may renounce all worldly goods and desires when we decide to heed Jesus’ call to follow him, but it is important to bed down that clarity of commitment and engagement with some wise practices and habits to keep its edge sharp.

John Wesley famously exhorted his followers to ‘Spend as little as you can, to save as much as you can, to give away as much as you can,’ which has inspired generations of Christians to live more simply, and support works of mission and charity around the globe.

|

|

| The Worship of Mammon by Evelyn De Morgan, 1909. |

Today we know that the cheapest goods are often the most exploitative, and that the basic level of spending to function in the modern world is a little higher than the 28 pounds sterling that Wesley survived on for his full adult life.

But the nub of Wesley’s challenge remains: is your bank statement a cogent witness to your professed life of faith? Are you marshalling all of the resources that will pass through your hands in the course of your lifetime in line with the values of Jesus’ upside-down Kingdom?

How can you inoculate yourself against Mammon disease, while still functioning in the 21st Century? There are three vaccines we can all access: accountability, stewardship and generosity.

We can all too easily lose perspective when making financial decisions alone or with our partner. The good news is that sharing major decisions about our financial affairs with those who know and love us and share our concern for responding to the needs of the poor can be very liberating. Jesus himself was happy to take financial issues into the public domain, with one important clarification: he was very strong on keeping the details of our giving to the poor private so as to preserve our integrity before the Father (Matt 6:1-5).

The fact that frank discussions about our financial affairs are rare amongst Christians is a worrying sign that we are playing by the rules of Mammon, not following Jesus’ way into sharing ourselves and all that we are and have. Find some people you trust, who share your deepest values and open up with them about your finances—the really nitty-gritty stuff—and you will find new depths of friendship and trust, new bonds of love, and a sense of freedom you never imagined.

If accountability provides a scaffold for making good financial decisions, stewardship provides the ethos. We own nothing! Every resource, every talent, every moment, every dollar that we have at our disposal as individuals, families or societies is God’s and is to be used for His purposes (Ps 24:1). Every financial decision then, must be seen in the light of whole life stewardship: making responsible decisions concerning what is at our disposal in accord with the values of the Kingdom of God.

The cheapest shirt, isn’t necessarily the one that reflects the best decision: where was it made, by whom, and with what fibre (see p. 13)? Every purchase you make rewards someone: creates revenue for them that means they will be around tomorrow. As you walk up and down the aisles, or fill your cart on the website, you are helping create the world of tomorrow: determining which producers will thrive, and which will fail, if they can’t adapt. This is a collective enterprise, the sum of all our decisions is what drives the economy. Marketers can advertise, influencers can peddle, but it is the purchaser that casts the dollar votes for the new world of tomorrow.

Accountability clarifies our vision, stewardship should be our framework for all financial decision making, but generosity is the best medicine for Mammon disease.

Give money away! Both in a planned, regular way and through spontaneous bursts of generosity in response to unexpected needs. The planned, regular giving builds discipline and an element of sacrifice as we commit to living more simply. The spontaneous bursts connect us to the generosity of God and the joy of giving, and make sure we aren’t just getting comfortable at a slightly lower living standard.

Of course, Jesus goes much further than just giving away a portion of your income, “Sell your possessions and give alms to the poor” he teaches his disciples (Luke 12:33). We have so rationalised this passage as referring to our priorities, that many of us have never sold anything, let alone everything, to be able to assist the marginalised and excluded brothers and sisters that Jesus’ identifies with in Matthew 25. This is a good thing to reflect on with your little accountability circle.

Making money work for good

|

|

My day job is to help people and organisations to invest the money they have saved, whether voluntarily (eg. to build a deposit for a property, or some other savings goal), or through the compulsory superannuation system that operates in Australia. Mobilising savings to create a better, saner world is critical if we are to address the economic and ecological challenges we face: from inequality to the over-fishing of the oceans.

|

|

When I began in 1997, we talked about ‘ethical investment’, which meant applying a series of ethical screens to a potential investment, so that clients would build an appropriate mix of investments that excluded activities that they did not want to profit from, and ensured their investments supported environmentally and socially positive alternatives. Our clients would buy shares in renewable energy companies, sustainable property managers, and metal recyclers, and avoid tobacco, wood-chipping of native forests, etc.

The good thing about the name ‘ethical investment’ is that it makes it clear that values are the driving force in the investment selection process. The bad thing is that it sounds ‘holier than thou’, and always begs the question: whose ethics?

Despite expectations to the contrary, ethical investment funds performed strongly, over long periods of time. One of the reasons is the fact that companies relying on socially and environmentally negative practices to make a profit are much riskier long-term investments than those that treat people and planet well. Whether through tighter regulation, the risk of consumer boycotts, or reputational and brand damage, businesses that behave destructively are at risk of seeing their markets shrink.

This gave major institutional investors and superannuation funds a way to engage with screened investments. Rather than using the language of ethics, they adopted a framework of risk management. It is now more likely than not that the super fund that is managing your long-term finances employs some sort of environment, social and governance (ESG) risk management framework. Some $1.3 trillion is currently invested in Australia in some form of ESG-screened funds.

However, while this risk management approach is a big step forward for mainstream fund managers, it rarely goes far enough for those wanting to drive change in the world and accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels to a more circular economy, where agriculture is regenerative, oceans revive, and the poor and marginalised are not excluded from the economic mainstream.

The new, and fastest growing, sector in the screened investment space has been driven by philanthropic and charitable funds and is known as Impact Investment. Every investment you make has some environmental and social impact, for ill or good, or perhaps a bit of both. Impact investments, though, are those that specifically target certain environmental and social impacts as a central part of the investment thesis. The investment has financial goals, but also embedded in the DNA of the project, is a commitment to solving a particular problem or creating a particular opportunity - and the investment manager commits to achieving those outcomes, and reporting on them, alongside the standard financial reports that we are all used to seeing.

Impact Investment includes such things as community solar funds that put rooftop solar arrays on halls and childcare centres, funding social enterprise start-ups like the not-for-profit Goodstart Early Learning, or the for-profit Sendle (carbon-neutral freight services). There are a number of fund managers launching impact funds across the full spectrum of the investment universe, from community banking, to early stage venture capital, infrastructure investments, commercial property, bonds, shares and even social programs to address things like recidivism in prisons, and support for children in out-of-home care to age 21.

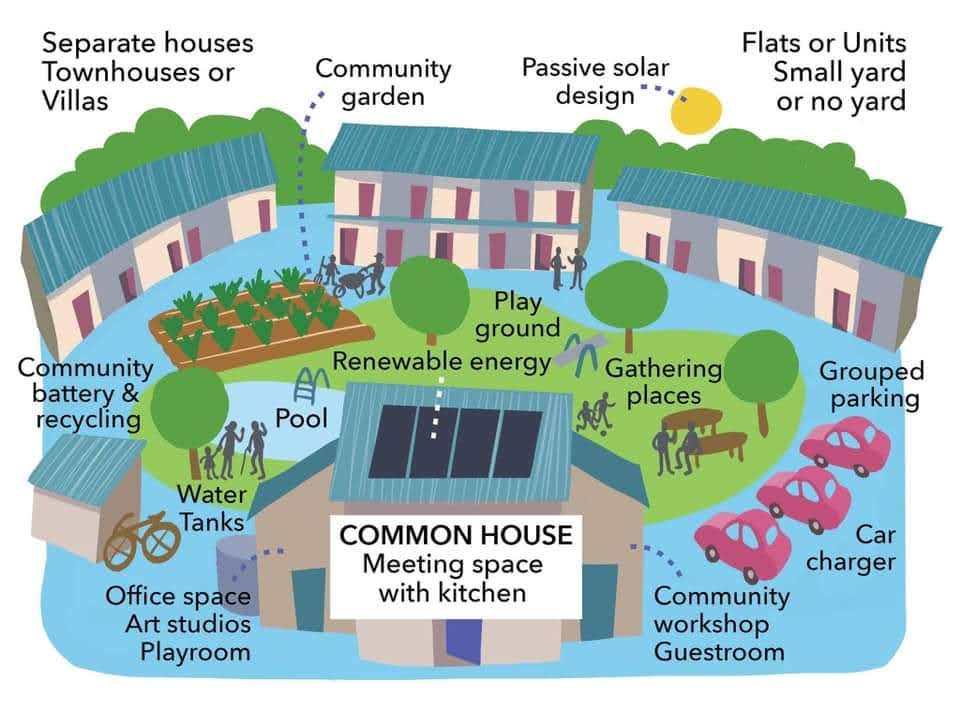

Co-housing concept (source: Co-housing Australia).

The other exciting area for many people, particularly those in Christian communities, is to look at co-housing and other ways of building a sharing economy. Pooling resources can be a great way to bring down the cost of living and free people up for more creative and flexible paid/unpaid work, and recreation options.

Sydney and Melbourne are both in the top 10 least affordable cities in the world. Mortgage is actually French for ‘the grip of death’—and many people know personally how a mortgage limits creative and flexible living options—and that has seen the proportion of people under 40 owning real estate in Australia fall to levels not seen in the post-WWII period.

We need better public housing, we need more long-term rental accommodation managed by organisations not individuals, and leases that can extend for longer than 12 months; but we also need creative solutions by people prepared to lobby councils for co-housing projects, shared tenancies, and co-locating to neighbourhoods and knocking down the backyard fences. Christian communities are well placed to nurture and encourage all of these things.

Sometimes we can feel overwhelmed in the face of personal financial decisions, not to mention the powers at work in the global economy. However, as we have seen, there are simple steps we can take to subvert the dominant narrative of consumer capitalism, and that lead us into a greater sense of freedom. When Jesus called on people to sell their possessions and give money to the poor, he didn’t leave them on the pavement with nothing. He invited them to join him, and his little band, where life was rich, resources were shared, and the poor and marginalised were specifically included. This is our invitation too.

Trevor Thomas is the managing director of EthInvest. Prior to this, he has worked in economic development in South America and on the staff and board of Tearfund Australia.